Yesterday’s schools

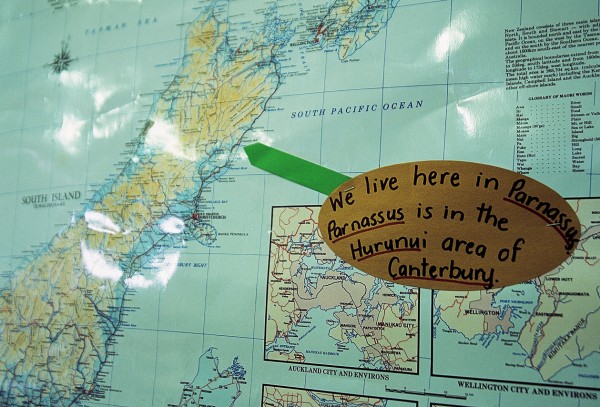

Small class sizes, dedicated teachers, a school backed by willing, committed parents—it’s what every educationalist dreams of—and it’s happening in small rural schools around the country every day. Here all the pupils of Parnassus School in North Canterbury line up on their netball court.

It’s Pet Day at a small rural school in Hawke’s Bay. There are working dogs, farm cats, lambs, spiders, even a horse. There are vegetable animals and sand scenes. Past pupils judge pavlovas (made by mothers) and sponge cakes (made by fathers) for the best dressed. The winning entries are auctioned off by the local stock agent.

“There is always total involvement. Kids auction muffins and biscuits. Older people come along. It is a wonderful family day,” says Jacky Stafford, past chairwoman of the board of trustees of Oueroa School (roll 28), near Waipukurau, education spokeswoman for Rural Women New Zealand and chair of the Rural Education Reference Group.

As of July 2003, nearly 42 per cent of New Zealand’s 2179 primary schools have had rolls of fewer than 150 pupils, while 20 per cent have had rolls of fewer than 50. Most of these schools are in rural communities. More integral than the once ubiquitous post office or local church, the rural school is now the focal point of its local community. Indeed, it may be the only building to bear the name of that community. Plenty of rural districts lack shops and may have only a school and/or a community hall as tangible manifestations. A rural school is an indicator of economic well-being and social unity, a reference point to local and national history.

“A school can be the hub for a rural community,” says Jacky. “In a city school you may not know all the teachers and parents. Your child might go to a sports group or cultural group with kids from other schools. But in a rural community you know the teachers, you know everybody. The school is an excuse to get together. It’s the glue that holds the community together. For new families, it’s a way of meeting people. You don’t have many other social opportunities—a lot revolves around the school.”

The special nature of rural schools made a strong impression on Takaka parent Penny Connolly. The small Motupipi School attended by her two sons was, she says, like a family.

“There is a kind of unconditional caring, because they know so much about the social history of the child. And as a parent you know everyone. The principal would meet you at the gate every day. You were parent help for half a day a week. For every sports day or fund-raising event there’d be a huge turn-out. You knew every child and every parent. And the school embraced integrated learning. A pod of whales was spotted in the bay one day, just as three school buses arrived at the school. The buses waited and the principal took all the kids back to watch the whales chasing seals. The buses followed the whales when they moved further up the coast, so the kids could watch them catching stingray. That became a lesson in geography, maths and biology. They learned about migration patterns and how old the whales were. The teachers really do go beyond the call of duty.”

[Chapter Break]

In school-houses, stand-alone classrooms, weathered halls and state-of-the-art adventure playgrounds throughout the country, rural schools tell the story of New Zealand, beginning with the arrival of European families from the mid to late 19th century. As family groups settled in rural areas, land was donated and temporary staff accommodation offered to help found small one-room schools. Education boards were established to provide buildings and teaching staff, while local parents formed school committees to assist with fund-raising and to provide manual labour for any construction work.

Many of these early schools were forced to operate on an almost seasonal basis. Teachers, paid according to attendance, struggled to keep numbers up as bad weather and flooding interrupted transportation to and from school (usually by horse or dray), epidemics kept children in bed, and harvesting or haymaking required children’s help in the fields. Throughout the early 1900s, however, school rolls continued to grow, with classrooms of up to 100 pupils sparking calls for new buildings or further temporary accommodation.

These fledgling institutions, with their small clusters of wooden buildings, became the linchpin of local rural life. In many areas the school building predated the community hall, thus serving—and in many areas continuing to serve—as the social centre of the district. According to one 1925 report, the school was “the most critical of rural facilities for the welfare of the community”.

Between 1935 and 1939 a government policy of consolidating groups of country schools was pushed ahead, driven by the idea that children in rural areas lacked the educational opportunities of town children. Protests, however, were long and loud as country communities fought, often successfully, for the retention of this vital part of their lives.

Old records provide ample evidence of the importance of local schools to rural districts. The local Home Guard used them for meetings and parades. They provided a venue for events such as picnics, fancy-dress balls, card evenings, euchre parties, agricultural days and concerts, which attracted families from all around. School halls were used as polling booths; school libraries served as community libraries. The school newsletter was a community’s information lifeline. School sports facilities were used by local rugby, cricket and tennis clubs, while a flurry of school swimming pools in the 1950s, during the post-war baby boom, offered the wider community an alternative to the river or beach.

In 1988, a governmental inquiry reported that schools, particularly rural schools, performed a wide range of functions beyond the provision of education. They were meeting places, the report said, reinforcing a sense of community and serving as a “communication hub” for the district. Rural schools were also seen as playing an important economic function:the presence of a school encouraged farm workers and their families to come to, and stay in, rural areas, and in so doing had a direct effect on the value of neighbouring land.

A school, said the report, also acted as a marker of continuity, something that held together the fabric of a community, indicating the well-being of a district and the active investment made by the community in the education of its children.

[Chapter Break]

Looking out over Foveaux Strait, Aparima College in Riverton, with a roll of just over 200, reflects a mentality that defines many rural schools in New Zealand: community involvement, flexibility and a commitment to the value of rural learning.

Bordered by the river estuary and the foreshore, the college is one of several rural high schools in the country running a Gateways programme, offering courses in such activities as diving, chef work, engineering and tourism. The school works in with the local fishing industry, and plans to open a marine academy offering coastguard training, diving instruction (supported by thriving tourism ventures in nearby Fiordland) and fishing experience. Already some students are involved in building boats for local use as part of a yacht-building course.

According to principal Kaye Day, the flexibility of the new National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) assessment and qualification system has worked well for the varied requirements of rural communities. Her college has combined some subjects, such as geography and history, alternates others on a yearly basis, such as music and drama, and has introduced yet others, including equine studies and agriculture.

“We’re tailoring our courses to meet the needs of the students, working in with local industry, trying to incorporate career possibilities for our students so they can go on to fishing, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, coastguard work, Department of Conservation or tourism. Our kids can walk out the gate, cross the bridge and they’re at the coastguard station. A lot of kids volunteer for the rescue boat or the local fire brigade—why not build on these interests? Some of the skills they learn may lead to earlier acceptance in the army or navy, but many will keep them here. Local businesses are keen to offer work and careers.”

And once these students are involved, says Kaye, most of the employers want them to stay. “The biggest problem is ensuring that people don’t bypass us for the bright lights, making sure that people realise that quality education is being delivered at a local school. We’re only half an hour from Invercargill, so it’s always an issue. I’m proud of the innovative things we have done to keep children at the local high school. It’s good for the school, it’s good for the community and it works well for the children.”

Statistics prove her point. At the end of the 2002 school year, every leaving student went either into full-time work or onto tertiary education. It is the practical, hands-on, community-based approach to learning that seems to be one of the most enduring characteristics of the rural school.

“There is so much that a small school in a supportive community offers its students,” says president of Rural Women New Zealand Sherrill Dackers. “Rural school-children are encouraged to be individuals. They get individual attention, and they’re confident. They have the ability to achieve because they’ve always had that encouragement.

“Rural schools will always be known for taking their children on adventures. And a child who spends a lot of time doing projects is learning a lot more than those who sit in the classroom.”

[Chapter Break]

Consider Pigeon Bay Primary School on Banks Peninsula, a sole-charge school of 11 pupils ranging in age from 5 to 12. They’re beginning a unit on hydroponics. Some of them are growing herbs in milk bottles. A local restaurant, says principal Jennie Gardiner, may well be interested in the produce. Outside the classroom, overlooking the idyllic blue waters of the bay, a small stall offers tourists locally made mementos and the odd batch of fudge. Quality control, some very basic accounting and a hefty dose of entrepreneurship are just some of the skills associated with rural schools.

“We honour the children’s home life,” says Jennie, “and we use the environment that we live in—that’s part of our charter.” Which does mean, she goes on, that you have to think on your feet. A parent comes into the classroom to tell the teacher there’s a dolphin in the bay; six sheep wander onto the rugby paddock; a huntaway turns up at school—each presents an opportunity to drop the subject in hand and run with the new “learning moment”.

And PE? As well as joining forces with other peninsula schools last year for a regional version of the Olympic Games, the children at Pigeon Bay Primary lead the rural lifestyle, of which physical exercise is part and parcel.

“It just happens. These kids are always running and swimming. They live up hills. They’re exercising all the time.”

One of the most important differences between town and country schools is the multi-level learning environment at the latter. During a student’s six-to eight-year stint at a one-class school such as Pigeon Bay Primary, for example, he or she is exposed to a concept or subject two or three times, on each occasion taking it to a new, more advanced level. Same pitch, says Jennie, but different essential skills, and a pool of knowledge made wider as the older children help the younger.

Teaching whole families of children, often in the one classroom, further blurs the boundary between home and school. “Children go from a family situation in the morning straight to the classroom. They have to learn pretty quickly to get over who got the toy from the cornflakes box.”

The work is constant. For a country teacher living in a schoolhouse there are few occasions when the education hat is not being worn. Certainly the paperwork at a small rural school is no less burdensome than that at a large city school, and, for a teaching principal, management time is a luxury.

But help is never far from the classroom. At country schools parents tend not to drop their children off at the gate every morning; their regular involvement in school and their literal interpretation of primary education’s open-door policy reflect a deep sense of ownership in the community for its children’s learning.

On Pet Day and the like, the turn-out of pavs and sponges is huge. For a working bee, local farmers offer not only labour but also fence posts and the use of machinery. Library books are repaired by pupils’ mothers, the garden is maintained by the whole community. At a small school, the viability of school trips depends on the availability of transport (often provided by parents) and parent support. Particularly when a school was once attended by many of the parents, there is an enduring sense of ownership and mutual respect.

Kaye Day remembers her first day on the job. “I had parents come in and check me out and talk about how to teach their kids. It wasn’t being critical, but there was this expectation of the best. It took me a while to realise that this was a school that belonged to the whole district.”

With such expectations, the role of principal is vital. One of the most pressing difficulties faced by rural schools is attracting, and keeping, teachers and principals. With compulsory country service for beginning teachers long gone, unfilled vacancies, inexperienced staff (there have been instances of a second- or even first-year teacher, not yet fully registered, winning a principal’s appointment) and a high turnover seem to plague the rural education sector.

For new teachers and principals, far from their friends (a lot of farming families are older; young farm workers tend not to stay and settle down), families and professional support networks, the job can be overwhelming. And in a small community, all eyes are on the new staff member, especially if he or she lives in the school-house, in the school grounds.

As Jacky Stafford explains: “It is challenging for rural teachers. You are in a very insulated community. You may go into a local hotel and have one or two drinks, but any more and everyone will know. But if you don’t go, people will think you consider yourself above them.”

“When a teacher goes to a rural school,” says Sherrill Dackers, “it’s like being a rural doctor: they’re isolated from their colleagues, their opportunities to keep up with their profession are limited and their skills and knowledge of teaching may suffer. But a teacher who has taught at a rural school for a long time is probably one of the best teachers you can find.”

The skills needed by a rural teacher are considerable and extend far beyond formal requirements. Teaching five-year-olds and 12-year-olds in the same classroom; understanding, and being involved in, the community; having some knowledge of, or at least an interest in, milking, grass growth or lambing—these are all challenges that can be daunting to a city-trained teacher.

“They’ll need to know if Mum or Dad has had an accident,” says Jacky. “They’ll need to know what has happened and who is affected. They have to be able to cope with more personal stuff.”

They also have to realise they’re dealing with very busy people, says Jennie Gardiner. Parents won’t want to drop everything for a meeting when they’ve got 3000 lambs to be tailed. “It’s a matter of being culturally sensitive. You have to learn from the community.”

[Chapter Break]

The principals interviewed for this story all agree that a rural principal has to be a jack of all trades. In a single week they may start the races at the Easter sports, fix the school computer, take a few classes if a teacher is ill, pay their respects to a deceased community member, and take part in a community working bee.

Furthermore, in parts of the country that hold little interest for international students and where local business sponsorship is limited, funding is always a hurdle. Small numbers of pupils do not necessarily keep costs down. It is as expensive to mow a rugby field for a school of eight as it is for a school of 80, and for schools in once-busier districts the cost of maintaining empty classrooms can be debilitating.

For cash-strapped boards of trustees, the distance from the nearest town can add crippling dollars to each and every cost. The mileage charged by a tradesperson can be prohibitive. While computer technology is a boon for rural schools, budgeting for broadband internet access must cover installation, monthly bills and technical support. When professional development for a member of staff requires a six-hour round trip, a school has to pay not only for that person’s accommodation but also for the accommodation and services of a relief teacher. With every change in staff there is the financial burden of advertising and interviewing.

Since the 1980s, dramatic changes in rural New Zealand have had a huge effect on rural education. A growing number of farm amalgamations, an increasingly itinerant work-force, improved mechanisation and better roads and transport have seen the rolls of some rural schools plummet. Every year on June 1, small schools in dairying districts undergo a roll reshuffling as share milkers reach the end of their 12-month contracts and relocate. As funding is based on predicted pupil numbers, the arrival or departure of two or three families in a district has a major impact on school budgeting.

Changes in the forestry, wine and mussel industries have also caused population movements and have had an influence on local schools. So has the proliferation of lifestyle blocks, their owners driving each day from rural addresses to jobs in the city, their children in the back seat.

“Those families continue to live an urban life, and often they don’t integrate into the local community,” says Sherrill Dackers. “Invariably the children continue to attend their urban schools, going into town with their parents. The parents have achieved their dream to live in the country, but their mind-set is still urban.”

And, with the promise of more job and further educational opportunities in the city, school graduates often don’t return to settle and raise a family in their home community.

Such developments inevitably precipitate a drop in pupil numbers. This leads to fewer teachers being hired, which in turn leads to a smaller range of subjects being taught, which results in both a further decline in the number of pupils and greater difficulties in attracting and retaining quality staff.

[Chapter Break]

In the 1990s, under the government’s Education Development Initiative, communities, through their boards of trustees, were given the chance to review the schooling in their area to see if there were ways in which it could be improved—for example, by neighbouring schools amalgamating. Overall these community-driven initiatives went relatively smoothly, but the speed and scope of ministry-led closures and amalgamations a decade later has left some communities reeling. By the end of 2005, 26 schools will have been closed outright and, as a result of mergers, a further 73 will no longer exist. Just eight new schools will have been established.

According to Rural Women New Zealand, the closure of country schools puts New Zealand’s rural infrastructure and the sustainability of its agricultural economy at risk, as rural employers are unable to guarantee a local education for their workers’ children.

While there are times when it is sensible for schools to close, or for two or three to amalgamate, Sherrill says such moves have to be weighed up against transport issues (an hour’s bus trip can deliver weary children to the classroom) and the impact on the community as a whole.

“Every time a school closes it means not only that parents have to send their children further away but, because there isn’t a local school, the community declines. Fewer workers will come because they want to know that their kids will get a good education.”

For Colin Tarr, president of the New Zealand Educational Institute Te Riu Roa, the closure of a school is also a loss of history.

“With a school there comes a sense of belonging. If you look at some of these rural communities, the old Four Square store is boarded up, the village hall is in disrepair, the post office sign has faded and the Mobil petrol station is a rusting edifice. The last physical sign of that area is the local school. Take that away and you’ve taken the last community focal point.”

Colin tells the story of a recent meeting with a young man he used to teach at Morrinsville Intermediate.

“At Morrinsville we took kids from all over—12 country schools and two town schools. I asked him where he’d come from. He said: ‘It used to be Tahuna. Now it’s just on the road from Morrinsville to Huntly.’ I remember the place. There was an old petrol station, an old hall and a shop. And the school. The school was merged; it’s gone now. For this boy that was the end. The place where he went to school that was his place to stand tall. Now he just lived on the road to Huntly.”

Colin admits rural schools are more expensive to run than larger urban schools, and the pragmatic approach is undeniably to amalgamate rather than duplicate. But the economic analysis of education, based on cost per head, does not do justice to the value of education. If a society was driven by the notion of public good, he says, the “cost” of education would be regarded as an investment.

Besides, says Riverton’s Kaye Day, the urban model simply does not suit every child. “When you look at children in city schools they have certain values and expectations, lifestyle and knowledge. To expect country children to be bussed into the city and survive and achieve is unrealistic. Their life experience says they need wide open spaces and small groups to do well. Some of our kids don’t cope with large cities.”

Colin argues that there are, and always have been, initiatives in place to support isolated schools. Before the Tomorrow’s Schools upheaval of 1989, school inspectors aided the cross-pollination of ideas, resources and events. Later, rural advisors travelled the hinterland, their cars packed with new books or teaching aids, able to take a class while teachers took time out to inspect the goods. While, with Tomorrow’s Schools, the contracting-out of services and major curriculum changes saw many of these roles melded into new positions, some, under the auspices of colleges of education, are still able to deliver the support most urban schools access locally.

Some school funding is tagged for costs incurred through isolation. Last year the government announced an increase in boarding allowances, giving families the opportunity to remain in remote areas while sending their children to secondary boarding schools.

[Chapter Break]

While some polytechnics are establishing satellite courses in rural areas, many country schools are finding a new lease of life by providing adult education or pre-school services. Based in the historic turreted homestead Menorlue (literally, manor on the lee), in the grounds of Ashburton College, the Community Learning Centre uses the school classrooms every day after 3.30 p.m. for a formidable range of courses. Following an annual consultation programme, adults or recent graduates can study languages or business skills, arts and crafts or art history.

Not only does the college have responsibility for 200 hours of adult education through the Mount Hutt College programme at Methven, but, following the purchase of a Nissan station wagon, it now also takes courses to the small halls and rural schools of Longbeach, Rakaia, Mayfield, Rokeby, Dorie, Winchmore, Pendarves—little names on an otherwise empty part of the South Island map. The impact on the community? Not only is Ashurton’s learning centre about reducing urban drift, it’s also about well-being. As director Dianne Moss says, a community that’s learning is a healthy community.

Throughout the country rural schools are consolidating their role both within their communities and further afield.

Over 1400 km north of Ashburton, Taipa Area School in Doubtless Bay is forging new links with the community. For two years its Whare Wananga, a learning centre modelled on a marae, has served as a vehicle for teaching te reo, local history, tikanga and computer studies. Increasingly, parents and graduates also are being encouraged to use the building for educational and cultural events. School principal Stephen Lewis says that the first step is to get local people feeling comfortable about coming to the school in the first place, many of whom had been put off learning institutions by their childhood experiences.

“As with most schools, you have to work to bring people in. I’m trying to increase the concept of the school in the community, trying to encourage users from outside the school gates. To raise the achievement of students, particularly Maori students, we need to have a much higher level of confidence and trust between the local community and ourselves. Linking into the community outside the school is the best way to make sure we raise the expectations of young people in the local area. We need parents to raise those expectations, as much as ourselves.”

Stephen says that, particularly in an area that is struggling economically, a school is often a rural community’s biggest investment. Raising the profile of the school as the centre of the community, he believes, will encourage people to share a commitment to it and so help with the regeneration of the whole area.

Elsewhere, some schools are addressing the problems of funding and staff recruitment by sharing boards of trustees, principals or administration staff. Some are sharing teachers—a music or art teacher can float between two or three schools. And when these schools cannot find the staff or the necessary pupil numbers to run a subject, there is always one stalwart back-up.

In 1922, the New Zealand Correspondence School was established to provide distance learning “for the benefit of the most isolated children, for example, of lighthouse keepers and remote shepherds living upon small islands or in mountainous districts”. Now the largest school in the country, with a roll of 22,000 and an operating budget of $36 million, the Correspondence School is increasingly serving the needs of dual learners, those students augmenting their standard school education with distance learning because of teacher shortages, a desire to study a niche subject, accelerated-learning needs or extra-tuition needs. Through dual enrolments the Correspondence School now has a working relationship with 98 per cent of New Zealand schools. In so doing, it offers a vital stopgap without which more students would move to city schools.

Overall, despite the financial plight of some very remote schools and the difficulty in recruiting and retaining staff, country education is in a healthy state. Rural communities continue to invest time and energy in their schools, and, for some teachers, the country classroom is the best place to be.

“There are high-quality principals and high-quality teachers who make the deliberate choice to be in rural schools,” says Mike Whittall, one of several ministry advisors supporting rural schools. “In the 1960s teachers had to go to a rural school and they’d often miss the city life. Now we’ve got people who are very committed. Some rural schools have closed, and when the demographics of the region have changed it’s probably for the better, but now, the fact that you can handle a whole range of situations and that you can teach at a multi-level school, as evidenced by having rural experience, is very highly regarded on a CV.”

Teachers in country schools talk about the rewards of multi-level teaching, the small class sizes, the close ties to the local community and environment, using the local environment to support curriculum delivery, and the lack of discipline issues (in a class of 18, says Kaye Day, it’s hard to get away with bullying).

And then there are the rural kids themselves.

There’s something about country children,” says Kaye. “It’s a combination of wisdom based on rural life and death, and real naïveté. They lack that sophistication that sometimes makes young people appear hard. They are very loyal and very honest. They lack the ability to temper what they have to say. It’s hard to take sometimes, but very refreshing. And I love the fact that I can walk around the school and the kids will say hello and I know the name of every one of them.”