What’s up DOC?

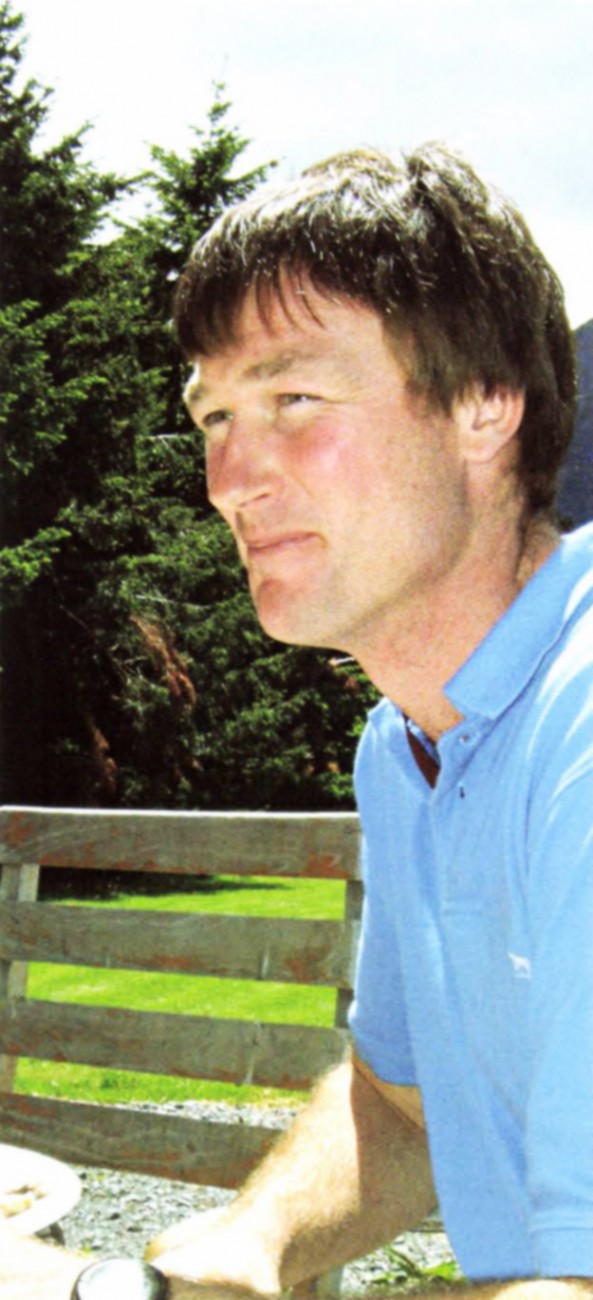

Ben Todhunter farms Cleardale Station in the Rakaia Gorge and is co-chair of the High Country Accord, an advocacy group for high country farmers. He was a 2006 Nuffield scholar and is a former chairman of the South Island High Country Committee of Federated Farmers.

Its a difficult time for South Island high country farmers.

Prices for Merino wool, their main source of income, reached rock bottom last year. Meanwhile those who own Crown Pastoral Lease titles are becoming increasingly worried about the security of their investment in their farms.

About 60 per cent of the land occupied by lessees has been earmarked by the government for a network of 22 high country parks and reserves. Some high country stations have been bought outright. But most of the land is being acquired during “tenure review”, a process introduced in 1998 which allows farmers to sell their leasehold rights to the Crown, in return for getting freehold title to any land that’s not wanted by DOC.

It’s a concept that is meant to be win-win. The public gets more parks and better access to the mountains. Farmers get the Crown out of their hair and are free to develop their land for uses other than pastoral farming.

For some farmers tenure review has worked well. In most cases, little of their land was wanted by DOC, or they were in locations suited to lifestyle block subdivision or to high-value economic uses like vineyards.

But for many of the 250 or so remaining lessees, tenure review looks like win-lose. Either the Crown wants too much of their land, or it wants the higher altitude tussock country needed for summer grazing.

For farmers in this situation, staying with leasehold tenure has been seen as the best option. However,that has become much less tenable, with lands minister David Parker announcing in October that he will be adding amenity values, such as mountain views, to the formula used to calculate rents when they come up for review.

This leaves farmers in a cleft stick. If they keep leasing, higher rents may make their farms uneconomic. Yet tenure review may not leave them with a viable farm.

One answer to this dilemma comes from associate professor David Norton, a University of Canterbury ecologist. He says tenure review today involves drawing a line on the map, with one side going to conservation and the other into farming.

Standing amidst the tussocks of Glenfalloch Station in the upper Rakaia valley, he says the concept is flawed. It is based on the assumption that tenure change and the removal of stock will of themselves result in better outcomes for biodiversity.

He points to a pair of birds flying over the ridge, “Those terns don’t distinguish between conservation land and farmed land. Ecological processes use the whole landscape. There are two opposing forces—farming intensification and landscape preservation—which are squeezing out sustainable management in the middle.”

He suggests a better way to handle tenure review on many properties would be to leave most of the land in private hands, but subject to management plans, monitoring of biodiversity and legally binding covenants. These would provide for improved public access, protect landscapes and biodiversity, while enabling low-intensity high country farming to continue.

If the public and the Crown want to retain tussock grassland in some areas, and to allow native forest regeneration in others, then active management is needed to achieve this, Norton says.

“The high country used to be a woody environment, right down to Central Otago. It has been heavily modified by 600-800 years of human settlement. Initially by Polynesian and then European fires, then by overgrazing by huge numbers of sheep in the early days of farming, followed by rabbits.”

These days, with sustainable sheep farming, little burning and rabbits under much better control, Norton says landscape change is being largely driven by invasive species like gorse, broom, Cotoneaster, willows, Douglas fir and Hieracium.

“DOC has limited resources and the kiwi is going extinct on the mainland. The commonsense thing would be to get farmers to manage the high country, so the department can get on with its priorities—like saving the kiwi,” he says.

Chas Todhunter, lessee of Glenfalloch Station, drives over most of his easier country several times a year, with a pack of herbicide prills at the ready. But even so, he says weed control in the high country is a huge challenge.

Todhunter has entered tenure review. And while he has yet to get a preliminary proposal from the Crown, he understands DOC is likely to want 90 per cent of his land. Much of that 90 per cent is rock or shingle, but it includes land with assured summer growth.

He says that while most of the farm’s carrying capacity is in the 10 per cent DOC doesn’t want, the conservation land provides essential grazing in summer when the flats are growing feed for winter, or going brown in the sun. “If DOC gets what it wants, it knocks out our flexibility,” he says. “A property which has been summer-safe won’t be.” Todhunter says there are no “massive opportunities” for him from tenure review. The farm has no potential for subdivision or high value crops. So he will try and reach a compromise with the Crown.

“A couple of years ago my lawyer almost laughed in my wife’s face when she questioned the security of our leases. Now I can see the basis for her concern. Being rented off the property has the same effect as being legislated off.”

With her mother Iris, Kate Scott farms Rees Valley Station at Glenorchy at the head of Lake Wakatipu. Like Glenfalloch, most of their farm is sought by DOC.

Kate hopes to eventually get the whole station covenanted during tenure review. She’s aware that DOC doesn’t like the concept but hopes the Parliamentary Commission for the Environment, which is investigating tenure review, will see merit in it.

A fourth generation runholder, she laments the loss of the high country heritage which will be an inevitable result if tenure review continues the way it has.

“Our vital high country farming culture will become a focus for museum and theme park reconstructions, with as much life, vitality and reality as the restored ruins of early mining settlements in Central Otago.”

Yet if the high country farming heritage is so important to New Zealand’s cultural identity, and high country farming is sustainable, why are urban people so willing to sacrifice it in favour of conservation parks?

Scott says townsfolk are fascinated by the romantic aspects of life in the high country, while at the same time “being absolutely willing to believe that it’s horribly bad for the environment”.

“Combined with the perception that the mountains are public land, there is a strong feeling of national ownership of the high country,” Scott says.

“Many believe that ‘wilderness’ functions as a sacred space, set apart from ordinary mundane life. So who the hell are these farmers who are living there and using the natural resources to feed their bloody sheep?”

The contradictions don’t end there. Kate sees irony in the distaste the public has for factory farming and its simultaneous unwillingness to allow farmers to graze animals sustainably in a semi-natural state in the high country.

These attitudes are becoming increasingly public, with tenure review now a political battleground.

In a report released in early 2006, Fulbright scholar Ann Brower said tenure review was unfairly biased in favour of farmers—a conclusion Forest and Bird used to underpin a nationwide campaign to call a halt to the process.

For their part, the High Country Accord in November released a critique of the Brower report by Victoria University economics professors Lewis Evans and Neil Quigley. Brower, they say, made a number of errors and her claims are “totally unfounded”. This critique has since been disputed by Brower.

Meanwhile, tenure review itself has effectively halted, with officials responding to a decision by minister Parker to scrutinise the details of every tenure review proposal.

For their part, high country farmers have decided to test in court the legality and fairness of the government decision to include scenery and other amenity values in its rental valuations. The first step will be a Land Valuation Tribunal hearing looking at the assessment of rent on a typical high country farm. Given the importance of this issue to both the Crown and lessees, a final ruling from a higher court is almost inevitable.

The stakes are high. Geoffrey Thomson of Mt Earnslaw Station, near Glenorchy, says if the government, egged on by Forest and Bird, sticks to its present path the future of the high country won’t be determined by the principles of sustainable land management.

“It will be determined by the unfounded belief that biodiversity protection is possible only under state ownership, and the doctrine that sustainable production has no place in our wild lands.”

In the words of Kate Scott, there’s a real danger that “high country farmers will all become ghosts on the landscape, rattling their dog chains and vanishing into thin air”.