Volunteer Service Abroad

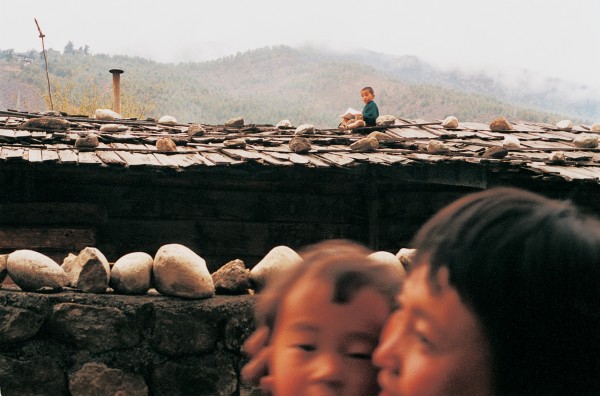

A group of Masai in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Conservation Area take a break from pastoral duties. VSA launched its Tanzanian programme in 1987 and has since placed some 63 volunteers in the country, working on everything from agriculture to health and local government. Over the last 42 years, VSA has mounted programmes in 32 countries. As VSA’s manager for Africa (1988–1996) and external relations (1999–2003), Trevor Richards is well placed to examine the changing face of VSA, aid and development.

When the philandering husband in TVNZ’s 1987 cult drama Gloss tells his long-suffering wife to pack her bags, her pathetic question “What am I supposed to do?” brings the response: “From now on I don’t care what you do. You can wear sensible shoes and a man’s watch. You can join Volunteer Service Abroad or take up china painting. Anything so long as you do not interfere with me.”

Pushed to explain his reference to VSA, he would probably have derided the organisation for being filled with do-gooders. In my 15-year association with VSA, the strongest critical comment made directly to me came from a retired businessman: “They [whoever “they” were] just breed like rabbits. It doesn’t matter what you do, so why do you bother?” The question was definitely rhetorical.

Which is a pity, because, ignoring the premise on which it was based, it’s a good one. What do organisations like VSA do and what do they achieve? Is a good conscience the only reward?

Development agencies are a phenomenon of the second half of the 20th century—so much so that the last 50 years could be called the age of development. One political commentator has written: “Like a towering lighthouse guiding sailors towards the coast, ‘development’ stood as the idea which orientated emerging nations in their journeys through post-war history.”

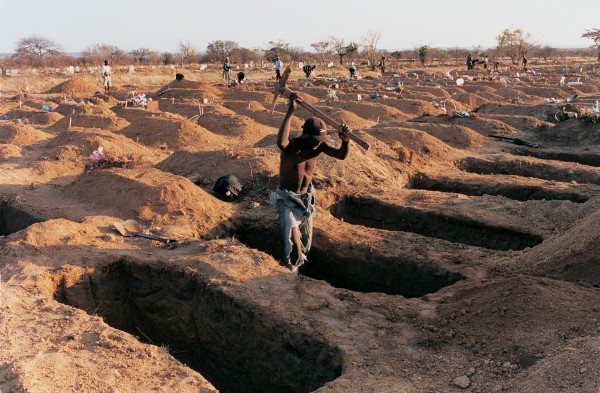

However, the journeys undertaken by emerging nations have not always been journeys of triumph. Today, the accusing finger is pointed at Zimbabwe. A few years ago it was Rwanda and Burundi, and before that Somalia, Ethiopia and Uganda. Asian, Latin American and Pacific nations have also undertaken their share of “failed” journeys.

Development agencies work in a complex world. They are just one of a host of forces capable of changing people’s lives. Development assistance is no cure-all. It is not a wand that can be waved to eradicate the effects of harmful trade and investment, of military oppression and human rights abuses. It cannot turn history on its head. VSA’s new CEO Deborah Snelson knows better than most about the fine balance that goes into effective development. For 16 years, she worked in Africa, pioneering approaches that enabled villagers to benefit from the wildlife they lived alongside.

She saw plenty of examples of outstanding change brought about by meeting local needs. She also witnessed heart-breaking waste where projects weren’t focussed and good opportunities lost. She says VSA has evolved through a time of huge change in the development world and she is proud to be leading an organisation that has responded well to that change.

[Chapter Break]

When VSA was formed in 1962, it was very much an organisation of its time. A mood of confidence and optimism prevailed. In his inaugural address in January 1961, United States President John F. Kennedy had held out exciting prospects for those who wanted life to be about more than just getting and spending.

He told the world that for the first time “man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of poverty.” The challenge was exciting, noble, inspiring.

VSA, in common with many similar volunteer agencies established in the 1960s, started life with an uncomplicated goal. Neville Peat, author of The VSA Way, writes that in the organisation’s early days, its purpose was “to develop friendship between New Zealanders and the people of the countries to which the volunteers were sent. Mutual goodwill and understanding underpinned the whole effort. The social and economic good that might eventuate from the volunteers’ work was implied rather than stated.”

During its first decade, volunteers were sent to Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu, Bangladesh, Brunei, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and South Vietnam.

But change was not far away. Returning volunteers began speaking what for VSA was a new language. Friendship, goodwill and understanding, while still important, were no longer enough. The word “development” entered the VSA lexicon:

“One can’t understand development until one understands oppression”; “Aid without development is not on.”

In 1974 a new course was set. VSA’s objectives were expanded to emphasise a developmental role.

Not long after I had joined the staff of VSA in 1988, an activist friend cynically observed that such organisations were little more than “well-meaning international temping agencies. The rhetoric of development is there, but that’s as far as it goes.” At the time I regarded the comment as unfair, too slick—and still do—but I could also see where my friend was coming from. I don’t know what he thinks of VSA now, but his position would be much more difficult to defend today.

Since 1962, and particularly since 1990, the changes in VSA have been substantial. Whom VSA sends abroad, where it sends them and what it sends them to do are all very different today from 40 years ago. This is hardly surprising. As noted already, development agencies are a post-World War II phenomenon, and they have found much to learn during the period in question.

One obvious change in VSA is the age of its volunteers. In the early years they were mostly much younger than they are today. For instance, between 1964 and 1974, VSA sent 318 17-and 18-year-old school-leavers on one-year assignments (adult assignments were for two years) in South-east Asia and the Pacific. These youngsters became media darlings, working such PR magic that many New Zealanders still believe VSA volunteers are young people. In fact, although VSA continues to appeal to the young, older people have increasingly swelled the ranks of volunteers. Those currently in the field range from their mid-20s to their early 70s, and the average age is approaching 50.

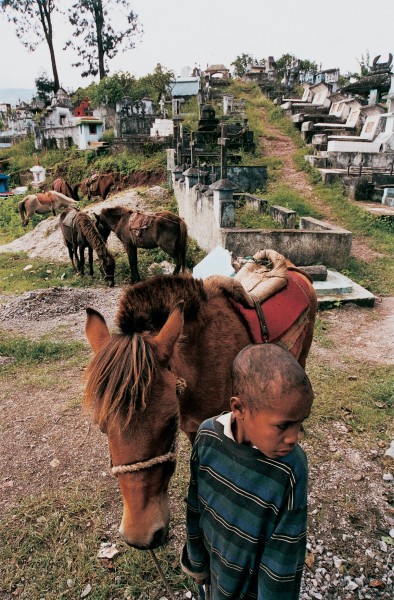

The location of VSA’s programmes has also undergone major change. In the early ’60s, the Pacific region and Asian countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei and Indonesia received most support. Come 1990, with the end of the Cold War, the crumbling of apartheid and altered relationships within many regions, programmes were launched in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Tanzania, South Africa, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. A reconstruction programme in Bougainville was established in 1998. A similar programme in East Timor followed in 2001.

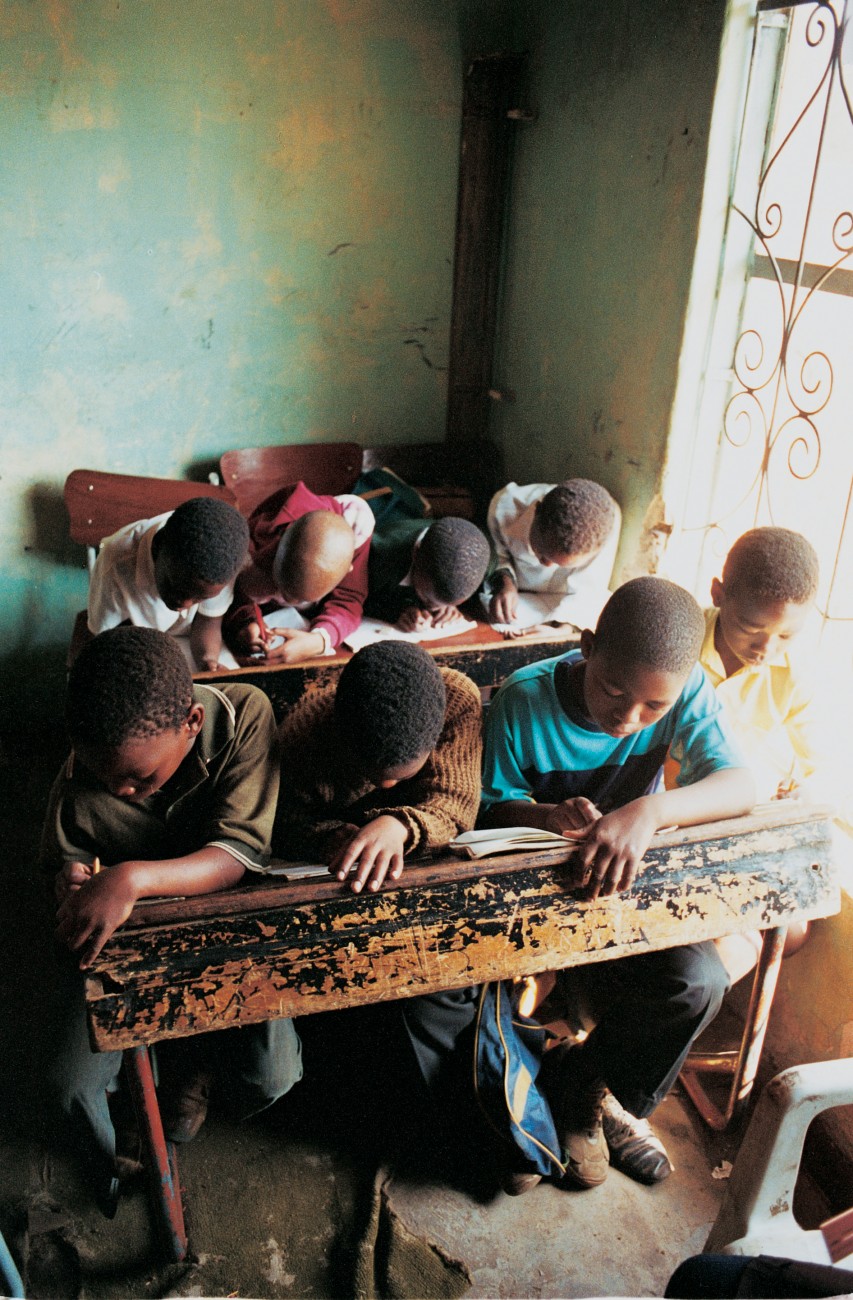

Of the 147 assignments in which VSA volunteers were engaged in the 2003–2004 financial year, 25 were in Africa (Tanzania, South Africa and Zimbabwe), 42 in Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Bhutan and East Timor) and 80 in the Pacific (Samoa, Tonga, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea—including Bougainville—Niue, Kiribati and Tokelau). Forty-four per cent involved education and training, 11 per cent economic development, 14 per cent health improvement, 7 per cent community development, 13 per cent building infrastructure, 5 per cent agricultural work, and 6 per cent the harnessing of natural resources.

Programmes in the early 1990s reflected a major shift in VSA’s approach to development issues. No longer was it simply a case of schoolteachers teaching and hospital nurses nursing. In VSA’s 40th anniversary publication, New Zealand Abroad, Margot Schwass wrote: “A VSA nurse today is more likely to be running a workshop or advising health department officials than weighing babies in a village clinic. Classroom teachers have made way for education volunteers whose role is to share new methodologies with local teachers.”

Although the philosophical adjustments underlying these changes have been invisible, they have been crucial.

During the Cold War, most development theorists belonged to one of two camps. US economic historian Walt Rostow’s modernisation theory argued that what was needed to develop and build the economic strength of poor countries was a massive injection of new technologies and development capital. According to Rostow, the cause of the social and economic problems countries faced was located within their own national boundaries.

Others believed that the obstacles faced by the “underdeveloped” world were caused in substantial part by the economic policies of rich and powerful industrialised nations. They promoted the dependency theory, which argued that for development to occur, the nature of the relationship between rich and poor countries needed to change. According to this view, the causes of social and economic problems facing poor nations were largely external.

The causes of global, regional and national inequalities continue to be argued over. A new school of theorists is elevating the importance of civil society in the development process, and integral to this approach is a rethink of what constitutes progress. Poverty alleviation, social equality, gender equity and environmental sustainability are advanced as important goals.

Today, VSA’s view of development centres on partnership, the interaction between volunteers and locals from which both learn and benefit. At the heart of VSA’s philosophy lies the belief that development assistance works best when local communities and organisations set their own goals and determine the type of help required to achieve them.

In many cases, what is needed most is neither money nor physical resources but skills, human enterprise and organisational capability. VSA volunteers can contribute expertise, experience and energy to strengthen local capacity to solve local problems. Development is most effective when it encourages and enables people to participate fully in the decisions and processes that shape their lives, promotes the equitable distribution and use of resources, and strengthens local organisations and initiatives.

In adopting this approach, VSA has, since the early 1990s, acknowledged the importance of such concerns as gender and the environment. It has also placed growing emphasis on community development, human rights and governance issues. These have become increasingly important as conflicts have arisen within the Pacific region and in East Timor.

Given all of this, it could be argued that only two things about VSA have remained the same over the past 40 years. The first is that the word “volunteer” has always been something of a misnomer. VSA’s volunteers have never been such in any literal sense of the term. They are paid a monthly living allowance and small set-up and resettlement allowances, and provided with airfares and accommodation.

The second constant relates to funding. Since 1962 VSA has enjoyed bipartisan political support, and successive governments have matched rhetoric with funding. In the 2003–2004 financial year, VSA’s grant from the New Zealand Agency for International Development (NZAID) was $5.6 million—substantially more than its first, a princely £2500. However, since the early 1980s, governments have required VSA to raise 10–15 per cent of its income—around $500,000—from the private sector. This can be a real struggle.

[Chapter Break]

Komiti Tumama, in Apia, Samoa, is the sort of non-governmental organisation (NGO) VSA is increasingly being asked to assist. Comprising 460 village women’s committees representing over 6000 members, it seeks to improve the lot of Samoan women with respect to their economic, educational and health needs and to enhance the status of women while still operating within the local cultural milieu. In 1997, the group had a framework, a purpose and plenty of enthusiasm, but lacked the institutional strength to make much headway. When VSA volunteer Su’emalo Tonu’u was appointed to help give it greater impact, it had neither an established office, ongoing funding, nor an adequate focus for its activities. Now it has all three.

The art of making siapo (the Samoan name for tapa) had all but died out, and Samoans were importing tapa from Tonga to meet traditional obligations. With Su’emalo’s help, Komite Tumama organised the planting of paper mulberry trees and held workshops to teach women how to harvest the bark and beat it into cloth. People are selling it now and earning money.

The sporting links between New Zealand and South Africa, which so many people in both countries once sought to cut, are now stronger than ever. In 1997, New Zealand’s Hillary Commission and the Eastern Cape’s Department of Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture signed an agreement to develop rural and junior sports programmes.

VSA volunteer Rose Tuhiwai, a former Maori sports coordinator with Sport Hawke’s Bay, worked with the department from 2001 to 2003 to establish the Eastern Cape Village Sport and Cultural Council (VSCC). This was a sport and community driven initiative that brought clusters of rural settlements together for sporting and cultural activities. These clusters, each made up of 10–14 villages, were modelled on the Hillary Commission’s marae-based programmes.

This is a new concept in South Africa. Rose sees the combination of sports and arts as having “huge potential”: “This is community development with a strong cultural influence.”

VSA’s South Africa field officer, Murray Benbow, says that the benefits of Rose’s assignment are highly visible. “It has motivated and generated a healthy competition amongst people. Sport helps build confidence and pride, and that is really important in an area where unemployment is around 65 per cent. I can see the programme uplifting people, and that’s a real stepping stone to a change in life.”

Since the early 1990s VSA has been increasingly involved in post-conflict work. Significant in this respect are its programmes in Bougainville and East Timor and,12 months after the evacuation of volunteers on the Australian troop-carrier Tobruk, its re-establishment in the Solomon Islands.

Terry Butt, VSA’s outgoing CEO, says that VSA’s experience in Bougainville enabled it to build its capabilities in post-conflict work, which has quite specific requirements. He believes New Zealanders have much to offer as volunteers in post-conflict situations.

“They have a reputation for being able to function without regard to the environment. A lot of other nationalities spend the first six months trying to change the environment so they can work in it. Our people tend to be happy to live like locals, without a lot of support. They just get on with it.”

In Bougainville, VSA was invited by the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade to explore the possibility of establishing a programme. When VSA visited the devastated islands in May 1998 to assess needs, the rehabilitation of ex-combatants was clearly a priority. The keys to integration were seen as reconciliation, education and income generation. The centrepiece of VSA’s programme became the Arawa Carpentry and Social Development Association (ACSDA), established to give local people marketable skills while also rebuilding public facilities devastated in the bitter nine-year civil war (see New Zealand Geographic, Issue 46). Over a four-year period, five VSA volunteers helped build the association’s organisational capacity and taught building skills to more than 40 former combatants. The ACSDA’s contribution to reconstruction is now visible everywhere—in the refurbished Arawa Public Library, the TB ward at the hospital, the new classrooms at Keuru School.

In the Solomon Islands, where violent civil unrest erupted in 2000, VSA works in two provinces, both hard-hit by the conflict. Three volunteers are advisers to small businesses, helping stimulate economic development and create income-generating opportunities for local people. Two lawyers are serving as legal advisers to their respective provincial governments, supporting improvements in local governance and legal systems and thereby helping build a sound platform for future peace and stability. One is now closely involved in rewriting the Solomon Islands’ constitution.

[Chapter Break]

What motivates people to volunteer with VSA? Carolyn Mark, VSA’s recruitment and training manager, has been asked the question a thousand times. She joined the VSA staff in 1984, and has seen close to 1000 volunteers come and go and interviewed well over twice that number. She says there are three broad reasons people want to volunteer with VSA: they wish to do something of value—“to give something back”; they want to learn about themselves and another culture; and they’re keen to extend themselves by taking on a challenge.

Neil Bellingham, one of VSA’s first volunteers, worked in north-east Thailand from 1964 to 1966. He was motivated by the mood for change that infected the ’60s. “Internationalism was part of the climate of the times,” he recalls. “Many of us felt that in New Zealand we were well off and had obligations to less fortunate parts of the world. We felt change in the world was possible… Small things—small organisations, small countries, ordinary people—could make a difference.”

For Monika Fry, it was initially a sense of adventure that drew her to VSA. She taught in Vanuatu in 1977 and in Papua New Guinea in 1978. “When I was at high school, working each holiday in a Wellington fur shop, a nurse who had been a Red Cross nurse in trouble spots all over the world regularly brought her sealskin coat in for summer storage. She told fascinating stories of exotic locations. I remember hanging on every word and deciding I was going to do that too.”

Beth Allardice was a volunteer in Zimbabwe (1986–88) and field representative in Tanzania (1989–93). “The thought of volunteering had been ‘lurking’ for decades, along with an intense desire to travel in a way that would give me some knowledge of the reality of other people’s lives and a meaningful involvement with them.”

What do volunteers get out of it? Tony Browne was one of the 318 in the school-leavers programme. He taught for a year at Vureas School in Vanuatu (at that time known as the New Hebrides). “It is a truism that a volunteer learns more, particularly about himself or herself, than he or she can ever give a host community. For an 18-year-old, that imbalance was particularly marked… I learned both the richness and the hardship of a subsistence existence. And I prepared myself for university with an appreciation of the privilege of tertiary study that nothing in a New Zealand school could have given me.”

Today, Browne is director of the north Asian division of the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “More importantly,” he says, “VSA set me on the path that led to my making a career as a diplomat. At [Vanuatuan] independence in 1980, I was sent back for a few months to help set up their foreign ministry, and seven years later was appointed New Zealand’s first resident high commissioner in Vila. I knew a number of the cabinet ministers and officials throughout all parts of the government. One of the Vanuatu teachers with whom I shared a house at Vureas 21 years earlier was director-general of education, the other the head of a provincial administration. My Bislama, the local lingua franca, was still fluent.”

Monika Fry can relate to Tony Browne’s story. “My experiences living in Papua New Guinea and other overseas countries have provided a reference point for many things I have done. Last year I helped conduct a review of a health-education and sanitation programme undertaken in Eastern Highland schools. This was made successful with my previous knowledge of Papua New Guinea pidgin and understanding of the country.”

Bev Wickham, previously a VSA public health nurse in Cambodia (1992–94) and VSA primary healthcare advisor in the Solomon Islands (1996–98), thinks that she “became much more patient and less judgemental with people. I gained a realisation that it does not matter where you were born and what culture you belong to: people the world over have the same fundamental hopes, desires and dreams in their lives.”

Matthew Hall and Paula Barry have recently completed assignments with VSA in East Timor, Matthew as a forestry officer and Paula as a nutritionist. Before they left they spoke of how they felt their time in Cova Lima would benefit them. As Paula summed it up: “Working in a country where the culture is significantly different will give us a new perspective, and enable us to learn other ways of operating in our professions. It will also test our abilities to cope in difficult situations with no easy escape. And we’re hopeful there will be some really cool stories to tell on our return.”

How does VSA go about setting up a new programme? While many aspects of the process are country-specific, others are common to all.

When I joined the staff of VSA, programmes in Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Botswana had already been established. The initiative to launch VSA’s South Africa programme had come from the ANC, in the first instance from Makhenkesi Stofile, now premier of the Eastern Cape provincial government, and a resolute opponent of New Zealand’s sporting ties with the old regime. Visiting New Zealand in 1991, he had suggested that VSA investigate the establishment of a volunteer-based development programme: “The regime is busy getting its friends into the country—why shouldn’t we get some of ours in?’”

VSA was initially dubious. Wasn’t South Africa rich? Didn’t other countries have greater need? Who would VSA work with? How safe would volunteers be? Kwa Zulu Natal and the East Rand were on fire. Besides, there was no guarantee that the talks taking place between the old regime and the ANC and others would lead anywhere positive. How realistic was the establishment of any VSA programme in the near future? In late 1992, together with VSA’s field representative in Zimbabwe, I made the first of several assessment visits to South Africa.

Before my departure, Peter Harris, who had emigrated from South Africa to New Zealand in 1974, suggested that VSA work in the Eastern Cape, one of the poorest regions of the country. Three-quarters of the population were unemployed or underemployed, and over 60 per cent were functionally illiterate.

The community organisations that had developed under apartheid to address basic human needs were potential project partners. New Zealand enjoyed some standing among those in the disadvantaged communities, the role of many of its citizens in the anti-apartheid struggle offering a bridge between VSA and local groups. The Eastern Cape was relatively free from political violence, and was not as likely to attract the development assistance that it was anticipated would flood into Durban and Cape Town.

Harris’s advice proved sound. The message with which I returned was clear: South Africa may be prosperous in comparison with many African states, but large parts of the country were every bit as desperate as elsewhere on the continent. I strongly believed that VSA could play a useful role.

VSA was one of the first agencies to launch a programme in the new South Africa, with volunteers starting assignments in voter education in East London in 1993. Since late 1994, VSA has worked in both urban and rural parts of the Eastern Cape’s border region, and more recently in the Transkei. During that time, volunteers have helped to build more than a thousand new houses in the former coloured township of Buffalo Flats; to provide water in remote rural areas of the former Ciskei Bantustan (one of the Black African “homelands” abolished in 1993); and to bolster indigenous NGOs and local government. More recently, they have worked with the provincial Department of Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture.

While in every country history needs to be considered before such projects are embarked upon, this is especially true in South Africa. When whites and blacks interact, 350 years of history have first to be negotiated. As William Faulkner wrote of the American South: “The past isn’t dead—it isn’t even past.” This makes for very tense relationships. At a shebeen in Mdantsane, a sprawling black township outside East London, an elegantly dressed black banker sighs when asked about the future: “Our patience is being met with white defiance. Too many of them just don’t care. They act as if very little has changed. They certainly haven’t.”

Rose Tuhiwai, Camille Kirtlan and other volunteers working in the former Ciskei Bantustan know what he’s talking about. As Rose, who is Maori, says: “If Camille and I are together and I ask a question of a group of whites, they will reply to Camille. Whites talk openly to Camille in front of me, often disparagingly, about blacks and coloureds.” Such people are not exceptional; they can be found throughout South Africa. They live in electronically guarded fortresses, have maids whose surnames they haven’t managed to remember, and drive BMWs, Mercedes and Audis. VSA volunteers in South Africa may enjoy better living conditions than those in some other assignment posts, but the society in which they operate is very complicated.

[Chapter Break]

Shortly after Tanzania gained its independence in 1961, the East African state’s first president, Julius Nyerere, observed that “whilst other people can aim at reaching the moon… our present aim must be directed at reaching the villages.” Over the five decades since, for many people in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Pacific much has changed—and much has stayed the same.

Sir Edmund Hillary, VSA’s founder president, wrote in the foreword of New Zealand Abroad that while the world can aptly be described as a global village for some, for others “their village is their globe, and it is a tough place… More than one person in five alive in the world today lives on less than US$1 a day. They didn’t ask to live in poverty, any more than we are responsible for living in affluence. The fact that we do is a blessing, and with it comes responsibilities.”

How does New Zealand face up to its responsibilities? What it spends on development assistance is only one consideration—which is probably just as well, as its record in this regard is not great. In the heady, pre–oil-shock days of the early 1970s, the Labour government declared a development-assistance target of 1 per cent of gross national income. It reached 0.52 per cent in 1975, the highest the country has ever achieved. In the 2002–03 financial year, the current Labour-led government spent 0.24 per cent (around $300 million), significantly below the OECD average and less than half of the 1975 figure. Only six countries in the 22-member OECD spent a lower percentage.

Another, more encouraging measure of New Zealand’s willingness to shoulder responsibility is its volunteer record. Since the formation of VSA, 2000-plus volunteers have worked in 32 countries. Collectively, they have served in Africa, Asia and the Pacific for more than 4000 years. It is a record of which Sir Edmund Hillary says “not only VSA, but all New Zealanders should feel proud.”

VSA’s volunteers seem to find particular favour in their host countries. Ten years ago in Tanzania we were investigating the requirements for a particular assignment, and it seemed to me that it might make more sense if an agency other than VSA was approached. I felt sure that some of the wealthy European agencies would be able to supply more by way of vehicles and other project equipment than was within VSA’s capacity.

“No,” I was told by a project partner, “we would rather have VSA. Your volunteers might not have the same access to funding and equipment as those from some other agencies, but the people you send are hard working, practical, and very happy to work with local people. We would like a lot more like them.”

VSA’s work with the ACSDA in Bougainville has earned enthusiastic plaudits. The project was unique in that VSA established it from scratch but with a view to eventually handing it over to local management and ownership. This took place at a ceremony on June 28, 2001. Michael Bankini, supervisor of the workshop, commented, “We have almost all the skills we need now,” and thought that within a year Bougainvilleans would be able to operate independently of VSA. He likes the VSA approach of providing people, not money. “It’s not good for us to ask for money all the time. Donors giving us money cause too many problems.”

Within developed countries, New Zealand included, attitudes to aid and development differ markedly. To some, their practitioners are the new missionaries; to others, they offer an important, and sometimes the only, avenue to overcoming global and regional inequalities.

Although development assistance is no panacea, it is one of the few means available for tackling poverty directly and has achieved much. A recent United Nations Human Development Report states that “the progress in reducing poverty over the 20th century is remarkable and unprecedented.”

To state just some of the more significant strides made in developing countries since 1960: life expectancy has risen by more than 20 years, from 41 to 62; child death rates have more than halved; those with access to clean water have doubled, from 35 per cent to 70 per cent; adult literacy has risen from less than 50 per cent to well over 60 per cent; the proportion of children out of primary school has fallen from more than 50 per cent to less than 25 per cent. But while it is exciting that such change can be achieved, VSA’s CEO Deborah Snelson says it’s no reason to relax.

“Change for the better is not irreversible,” she says, “and the widening gap developing once again between rich and poor nations threatens hard-won gains.” Regional variations are also huge. She mentions Papua New Guinea’s East Sepik province, where VSA is working alongside local health service providers and Save the Children. “Life expectancy is under 50 and infant mortality is one of the highest in the southern hemisphere.”

Bev Wickham holds dear two comments made at the end of her two VSA assignments in Cambodia and the Solomon Islands. “When I was farewelled from Cambodia, I was told that I had taught people to care about each other. When I was leaving the Solomon Islands, I was told that I had taught people that nothing is impossible.”

Trish Moriarty, until recently a general and obstetrics nurse, worked with PASADA, a Catholic agency supporting the poorest people living with HIV in Dar es Salaam. She says that a recent survey of people using the agency’s services asked what they liked about PASADA. “Fewer than five per cent gave the expected answers—‘the free food’ or ‘the free medicine’. Most responded: ‘They care about us here.’ For too many Tanzanians, hard times make compassion an unaffordable luxury.”

New Zealand Foreign Minister Phil Goff has described VSA as “one of the best investments and value for money we can possibly get.” And it isn’t only those living in Africa, Asia and the small nation states of the Pacific who are benefiting. Back home in New Zealand, the benefits are also very real.