The people’s national park

Twenty-six years old this year, the QEII Trust has helped nearly 1700 landowners establish convenants, all of which seek to preserve the natural environment for future generations.

Totara Berries, glowing like tiny orange beacons in the morning mist, send a succulent signal to passing birds that breakfast is served. A plump native pigeon is already crunching into them in the treetop over our heads. Arthur Cowan picks one and offers it to me with thick farmer’s fingers, his twinkling blue eyes daring me to taste it. The conifer’s little fruit bursts in my mouth with an intense sweetness, followed by an unexpected sensation: a resinous turpentine taste that reminds me of home renovation.

Arthur is gathering berries from a grove of sturdy podocarp trees that are guaranteed never to face a chainsaw. The seed harvest is part of an ambitious project to protect, restore and expand remnants of the towering forest that once blanketed this King Country farmland, Arthur’s home for the past 87 years.

After a quarter of a century of help from a New Zealand organisation, the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust, Arthur is beginning to see—and hear—the results of his work. The totara, matai and rimu seeds he has collected are growing into trees to feed pigeons and other native birds, which all seem to find that turps aftertaste something to sing about. Fenced off from stock and peppered with traps and poison bait to control introduced pests, the bush is thriving. Notch by notch, Arthur’s efforts are turning up the volume of the dawn chorus.

Pointing to a bush-cloaked hillside rising steeply across the babbling Waipa River, Arthur tells me, “Years ago, it was easy to hunt deer there, the bush was so sparse. Now you wouldn’t be able to see an elephant in all those trees.”

It was his aging father who initially charged him to protect their farm’s patches of native bush. To do so, Arthur and his wife, Pat, considered gifting the land to the government as a reserve. Then, in 1978, they heard about a new way to protect it in perpetuity while retaining family ownership.

The Cowans were among the first farmers in the country to sign up as partners with the fledgling Queen Elizabeth II National Trust to register a protection agreement on their land’s title. “It fitted our needs perfectly,” says Arthur. “It was rather marvellous we could get our bush protected, just like my father wanted.”

Over the past 25 years, hundreds of other landowners have taken the same course as the Cowans. Each has agreed to a permanent open-space covenant for their special place, enacting conditions and prohibitions designed to keep the area in its natural state. More than 70,000 hectares of land is now protected for all time by some 1700 covenants. Most of the land is in lowland areas—a part of the country which is not strongly represented in government reserves and national parks, yet which originally contained the greatest diversity of species and which is most accessible to the majority of New Zealanders.

Botanist Brian Molloy, the QEII Trust’s regional representative for the South Island’s Mackenzie Country, describes the network of protected areas as “the people’s national park,” because each covenant is a partnership between the landowner and the trust, in which the landholder is the built-in ranger.

As the concept has matured, covenants have been registered to protect not just remnants of bush but also Maori rock art, dinosaur fossils, penguin nesting areas, swamps and even public access to a favourite shellfish beach. The diverse mosaic of covenants continues to fill in around the country, reflecting changing attitudes towards land.

“We’re moving out of the pioneer phase,” says Gordon Stephenson, the Waikato farmer who came up with the idea of the QEII Trust. “People are thinking more about sustaining the land than developing it. We’re now the only country in the world with a queue of farmers waiting to put a restrictive covenant on their land for no financial reason.”

If it isn’t money, what is it that has motivated so many New Zealanders to give up forever their rights to develop parts of their property? This is the question I set out to answer in my journey to a few of the special jewels in “the people’s national park.”

[Chapter break]

The story of the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust begins in the Waikato in the early 1960s. While their neighbours were felling bush to develop more dairy pasture, Gordon and Celia Stephenson were worrying about how to protect the forest remnants on their Waotu farm, near Putaruru.

“Our neighbours thought we were mad to fence off our bush to keep the stock out,” Gordon recalls. But that was only the start. The couple were haunted by the thought of the land’s next owners cutting down what they were working so hard to preserve. “There was virtually nothing available to protect the bush and still keep it in private ownership,” Gordon explains. “I could have given it to the state for a reserve, but it is neither practical nor socially desirable for everything that needs protection to be in public ownership.”

Gordon started talking about his dilemma with other farmers he met through his position as national dairy section chairman for Federated Farmers. “A germ of an idea started growing for an organisation run for farmers by farmers,” he says. By 1973, he was referring to his concept as the Heritage Trust.

He convinced government officials to listen to his plan, even as the government continued to provide farmers with incentives to clear native forest. “I visited seven different Ministers of Lands, or acting ministers, over seven years.” When a furore erupted in the rural community in 1974 over a law change involving river reserves, Gordon says he kept quiet about the Heritage Trust in public for a couple of years, so as not to risk an antagonistic response that might have killed his proposal.

Eventually, his idea melded with Minister of Lands Venn Young’s plan for the provision of more open space for the New Zealand public. “By 1977, it was just a question of negotiating the words of the act,” Gordon explains. “Then, a fortnight before the bill was due to be considered by Parliament, Venn Young said the Muldoon government had thought of a cheap way to celebrate the queen’s silver jubilee, and—though I wasn’t happy about it—the name was changed from the Heritage Trust to the Queen Elizabeth the Second National Trust.” These days it’s often referred to simply as QEII, or—to avoid confusion with other similarly named organisations—the National Trust.

The purpose of the trust, as spelled out in the act, is “to encourage and promote the provision, protection, preservation and enhancement of open space for the benefit and enjoyment of the present and future generations of the people of New Zealand.” Open space is defined as “any area of land or body of water that serves to preserve or to facilitate the preservation of any landscape of aesthetic, cultural, recreational, scenic, scientific, or social interest value.”

The Stephensons were quick to utilise the new act, signing up in 1978 for New Zealand’s first open-space covenant, a deed restriction registered on the title of their land which prohibits all future owners from clearing their cherished bush. The covenant names the QEII Trust as trustee, as the act prescribes, with land-management decisions to be made in partnership with a board of directors that includes farmer members.

“I was very keen to see these covenants remain in the control of a farmer-dominated organisation for the very simple reason that farmers would have confidence in it and it would have a much better chance of success,” says Gordon. “Elsewhere in the world, similar organisations are urban-based, imposing their city ideas on rural communities.”

Such overseas conservation programmes are also usually sweetened with financial incentives such as government grants or other handouts. Gordon sees problems with this approach.

“If you get hooked on a grant system for the act of covenanting, it kills the whole process stone dead. Conservation should work on a different currency, not a dollar value. It’s too important for that. It’s not commercial at all, it’s something moved by the heart. Just like the way you don’t put a dollar value on your family.”

Once word got out about the new grassroots group, farmers “came out of the woodwork,” Gordon says, asking for details about how a covenant could work for them. QEII staff, based in Wellington, were deluged with requests for information.

“What intrigued me was why people were covenanting. I remember one farmer telling me, ‘I’ve cut down so much, and now my grandchildren will never know what it was like.’ New Zealand was just coming out of the pioneer stage, where the bush was an enemy. With the realisation that there was less and less around, people began to take pleasure in what was left.”

In the early days of the trust, many people predicted that the number of covenants being established would decline after the first flush. Lawyers and accountants also warned that covenanted land would lose value. Both predictions turned out to be wrong. Covenants are being established at a steadily increasing rate, with 200 formed in 2003 and 300 expected to be formed in 2004.

As to the value of covenants, farmers who have set aside their remnants of bush are discovering that there are, indeed, economic benefits. According to Arthur Cowan’s daughter, Rosemary Davison, who, with her husband, Graham, has covenanted a stand of kahikatea on their Otorohanga dairy farm, trees do more than provide a scenic backdrop. They also provide shelter and shade, which help both pasture and stock. Good shelter boosts pasture growth, thereby enabling land to carry more stock. And if animals use less energy staying warm by taking advantage of shelter trees, they produce more milk and meat.

Rosemary says there was another advantage to fencing off the kahikatea: “No more freezing mornings with the cows playing hide and seek in the trees at 4.30 A.M. Cows have a sense of humour, but to me it wasn’t very amusing.”

Conversely, had the Davisons not fenced off the bush, it would eventually have been destroyed by cattle. Heavy hooves prevent regeneration and damage the shallow roots of even mature native trees. As farmers become more aware of the value of sustainable agricultural practices in the marketplace, they’re realising covenants can increase the value of their farms, Rosemary says.

Protecting bush from felling or livestock damage is just the first step towards preservation, as the “built-in rangers” have discovered. Introduced predators, browsers and weeds are formidable adversaries. “When we fenced our bush, we thought we’d saved it,” says Gordon Stephenson as he gazes appreciatively at the richly textured forest which lies beyond his grazing sheep. “It took us a long time to realise we hadn’t finished the job.”

[Chapter break]

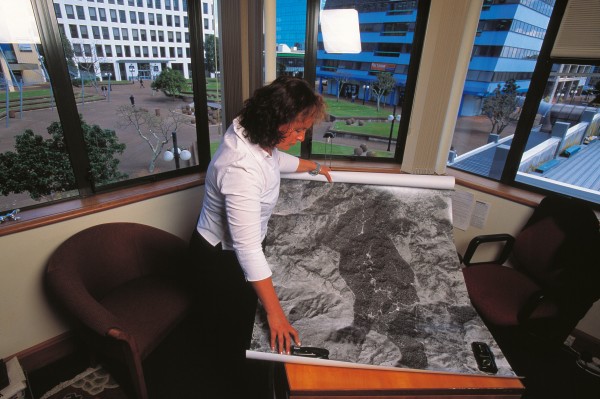

Maps, aerial photos and piles of paper cover Nick and Carron Perry’s kitchen table. Nick’s finger traces a line along a tree-lined stream as he points out the area he wants to covenant. The Perrys are signing up for their third QEII covenant on the family’s Kumeroa farm, and QEII’s regional representative for Hawke’s Bay, Marie Taylor, is taking them through the process. They discuss the type and quantity of fencing needed to keep stock out of the steep bush. The cost of this will be split equally between the Perrys, the trust and the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council, while the trust will pay for all the surveying.

Government funding for the QEII Trust has increased to nearly $3 million in 2003, up from $2 million in 2002, reflecting a push to increase biodiversity on private land. Other funds for the organisation come from donations, fees paid by its financial members and interest from investments.

“This new covenant will tie our other two together and give continuity,” Nick says, showing how the three covenants will cover the bush all along the stream and connect to a public reserve. Carron adds, “It will be a lovely walk all the way up the creek once it’s completed.”

Marie is taking notes for a report to QEII’s board of directors. She asks the Perrys about the property’s vegetation, soils, wildlife, special features and management needs, as well as any threats it may be facing. “Subdivision is a threat to all of rural New Zealand,” Nick tells her. He then asks Marie to make sure there’s an added clause that enables water to be taken from the creek for stock and allows access for four-wheel-drive vehicles at several creek crossings.

Included in the legal document that creates a QEII open-space covenant are three schedules that apply to the land in perpetuity. The first spells out the objectives: to protect, maintain and enhance the land’s open-space values, natural character, landscape amenity and indigenous flora and fauna. A covenantor can specify other objectives as well.

The second schedule details the restrictions imposed on the landowner. He or she may not remove rocks or native plants, plant anything other than local native flora, carry out mining or quarrying, subdivide, construct buildings, dispose of rubbish or allow livestock grazing—except with the prior written consent of the QEII board of directors (usually granted if the work is in accord with the covenant’s purpose as spelled out in the first schedule). Of the 1700 covenants registered over the past 25 years, fewer than two per cent have failed to comply in full with the legal requirements. In most cases, infringements have been minor, such as accidental road works or grazing.

The third schedule contains an approved management statement and clauses such as the ones Nick is asking for. “New language in the covenant document tightens up the public-access question considerably,” Marie tells them. “Public access is only with the owner’s prior permission.”

With the paperwork completed, the next step is to walk the perimeter of the area to be covenanted with a measuring wheel to find out how much fencing is needed. Nick says he’s been busy pulling out old man’s beard and other invasive weeds from the edges of the bush, while Carron has been trapping possums. Pigeons, bellbirds, tui, silvereyes, kingfishers, pied stilts, white-faced herons and pukeko all find a home in the protected areas, Carron says.

The Perrys consider themselves fortunate to have healthy bush to protect. “The farms nearby are scorched earth,” Nick tells me. “But this was in an estate with a lazy manager, so there’s some bush left.” It was Nick’s father who first signed up for a covenant on the farm. “Dad grew up when sheep were king. But there’s been a subtle shift in attitude. Most of the younger generation would like some variety, not just developed improved pasture.”

His eyes glow with pride as he points at the lush forest on the other side of the gully. “Look across there. It’s lovely. There must be 100 shades of green and 60 or 70 different shapes. Nothing like pine trees, all the same colour and all the same shape.”

The Perrys are thinking about turning one of their farm cottages into a homestay for extra income, with the added attraction of a creekside walk through covenanted bush. But they’re not protecting the native forest with money in mind. “It’s difficult to put an economic value on bush,” Nick says. “It’s just an intrinsic value. It’s priceless.”

[Chapter break]

With the issue of public access high on today’s political radar screen, it’s little wonder the legal language in QEII covenants now makes it very clear that anyone who wants to visit a covenanted area must first ask the owner’s permission. For some landowners, though, public access is a central provision in their covenants.

The Takaka Hill Walkway was officially opened to the public in June 2000, after the QEII Trust helped coordinate a volunteer effort to build a trail across part of the Harwood family’s farm. The walk passes among some of New Zealand’s oldest rock outcrops—marble karst formations with deep sinkholes—as well as through beech forest and open shrubland.

“We always thought this place was a bit like being on the moon,” says David Harwood. “It’s so unique it’s worth preserving. And if it’s special enough to have a covenant, it’s special enough for people to see it. It was a real dream, and the QEII Trust helped us do it.” David’s wife, Elva, is pleased to see so many families making use of the public track, which provides a spectacular panorama over Golden Bay, Tasman Bay and Kahurangi National Park.

Still, David admits, it wasn’t an easy decision to make. “Basically, you’re doing something that has a finality about it, putting something on the land for perpetuity. It’s a responsibility.”

The Harwoods’ son, Simon, acts as my guide along the walkway, talking about his family’s successes in controlling possums and gorse and chopping out errant radiata pine trees. He spots a distant rata, covered for the first time he can remember with crimson flowers. We scramble across fluted marble for a closer look at the results of the pest-control work.

Simon says he’s proud of the land and its public walking route. “We may own the land, but it’s only in our lifetime. It’ll be here for thousands of years.” He beams at the rata’s brilliant flowers, brimming with the nectar favoured by native birds.“There are some things money can’t buy.”

Covenantor Robert Buchanan, a former district nurse in Kaikohe, would agree. Public access is one of those things. When he won $4 million on Lotto, he bought Whangape Station, in the Far North, with an eye to public use and

conservation.

“I was always asking farmers for access so I could go fishing. Now I can provide it,” he says. “I’m one step ahead of the government. They’re talking about access to water, and I’m doing it.”

Permanent public access is the main purpose of a covenant he has placed on a four-kilometre pathway along the northern edge of the dramatic entrance to Whangape Harbour. The pathway leads to an expansive west-coast beach where locals like to gather shellfish and where endangered New Zealand dotterels nest.

“With QEII we’ve legalised a traditional coastal access. People need to feel they’re not breaking the law by using the path,” Robert tells me. Tramping clubs, pony clubs and other groups like to make a circuit, he says, by going up the farm road we’re on to reach the ridge-top, down to the beach, then back along the gorge. Along the way, they pass through a covenanted area of rare coastal forest with more than 200 species of native plant, including kauri, as well as historic Maori fortifications and kumara pits.

It’s a coastal attraction of a different kind that people come to see on covenanted property at Flea Bay, on Banks Peninsula. Around 2500 people each year use the privately owned Banks Peninsula Walking Track, stopping at Francis and Shireen Helps’ place to see a thriving colony of white-flippered penguins. (The white-flippered penguin is a subspecies of the little blue penguin.) Seven hundred pairs of this smallest of all penguins make their nests at Flea Bay, in burrows under the rocks or in nest boxes put out by Francis and Shireen.

“The bay is really noisy in the late afternoon with all the braying of the penguins,” Shireen tells me. “They need to socialise to breed successfully, and this is where they come for a big party.” On the other hand, the birds become bad tempered when they’re nesting, and like to spread out, so they need plenty of room. “It’s Indian file all the way up to the ridge at dark, up that steep track they’ve scratched out with their flippers.”

Monitoring the penguins involves banding them and keeping careful records of their nests and chicks, but it’s worth the effort, says Francis. “It’s a lot more interesting than chasing woollies,” he laughs.

Shireen checks her trap lines as we walk through the covenanted area near the water. Ferrets and cats are a big problem, although after a decade of trappingShireen says their numbers have declined significantly. “Eureka!” she shrieks. “I got one!” A fat stoat has been caught in one of her traps—one more predator which won’t be eating an more white-flippered penguin chicks.

Further north, Brian Plaisier is checking the traps in his patch of covenanted bush in Pelorus Sound. “The support and knowledge of QEII is important,” he says as we pass a tall rimu. “We came in as townies, and had never even seen a possum.” Eight years after signing on with the trust, he has caught more than 2500 possums, and even hires himself out as a trapper for his neighbours. He’s excited to see the bush and the birdlife gaining ground. “It’s magic. It’s all coming back to us,” he says.

For Brian and his wife, Ellen, it was love at their first sight of this forested plateau overlooking the Marlborough Sounds, even with its dead treetops, browsed by an army of possums. The Plaisiers, Dutch immigrants, were passionate about protecting the bush, and bought the land without even thinking about the access problems and rough lifestyle they would face, especially once they started a family.

“I want to hear a deafening dawn chorus here,” Ellen tells me over a lunch of noodle soup and freshly baked bundtcake on their little deck overlooking the shimmering turquoise sound.

“The best result from all my work on possums and pests is definitely the improvement in birds,” Brian says. “I counted 17 pigeons in a flock last week, because the food chain has been restored.” As if on cue, the rhythmic wing-beats of a kereru fill the air above us, and Brian jokes about using a remote control to create the effect. “I’m working on a dolphin next, to really amaze our visitors,” he says with a smile.

Rats are Brian’s current target. “The list is growing. Wasps will be my next project,” he says as we walk through a stand of silver beech, where non-native wasps are sucking up all the honeydew exuded from the lichen-blackened trunks. With us is the QEII regional rep for Marlborough, Philip Lissaman, whose earlier career, ironically, involved facilitating bush removal through the government’s Land Development Encouragement Loans of the 1970s. Brian directs his questions about the wasps’ life cycle to him, and he offers to help Brian obtain all the information he needs to poison the voracious pests.

On their remote property, which they call Tui Reserve, the Plaisiers run a small ecotourism venture. “It’s a nice circle,” Brian explains. “Overseas tourists come to see the protected area, and with their money we protect it.” He’s especially pleased with the way the covenant is set up in perpetuity. “For me, it’s very important to know that after my life this will still be here.”

[Chapter break]

Requests for public access are frequent at Glenmore Station, near Lake Tekapo. “A day doesn’t go past without someone calling to go climbing, duck shooting, picnicking or tramping,” explains Anne Murray over a cup of tea. “We’re happy for the public to enjoy this place, too, as long as they work in with our management and ask first. After all, we’re trying to make a living here.”

Anne and her husband, Jim, are talking with Brian Molloy, a respected high-country botanist and QEII rep, about the improvements they’ve seen in the native plants since they’ve been controlling rabbits, hares and other browsers.

Glenmore is a Crown pastoral lease that has been grazed for 150 years. It supports an astonishing diversity of native plants, intermixed with exotics that have become naturalised. Under the management plan for the 1000 ha the Murrays have covenanted, light grazing will continue. “It’s part of sustainable land management here,” Brian Molloy tells me. “If stock is excluded, there’s a risk the native flora will be taken over by naturalised exotics.”

When the Murrays decided to seek permanent protection for the land, they weighed up whether to go with the Department of Conservation or the QEII Trust. “We chose QEII because we’re also involved in the management decisions,” says Anne. “We trust the QEII people. They’re not political, they’re practical, and they have good communication with us. Plus we know a QEII covenant is there forever. It’s legally watertight through all land-tenure issues.”

Jim says his top priority is to look after the land sustainably. “When you become close to the land, you notice so much. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. The invasion of Hieracium hawkweed in our covenant was a major issue for me. I wondered what I was doing wrong.” With Brian Molloy’s help, he discovered that his practice of keeping the stock off the land in summer was allowing the hawkweed to flower and spread. Now Jim lets his sheep graze there during the crucial time to prevent the weed from flowering.

For Brian, the large protected zone is a wonderland of diminutive plants, some of which have never been described by scientists. Surrounded by jaw-dropping vistas of tawny tussock, glowing tarns and cloud-wreathed peaks, he gets down on his knees to examine a myriad of plants no bigger than a fingernail. His notebook is starting to fill up, and we’ve only gone a few steps. It’s true what they say: you never get tired walking with a botanist.

Rare native plants of somewhat larger stature were discovered recently on Sir Peter and Lady Fiona Elworthy’s property at Craigmore, near Timaru. As a result, the couple are to covenant their stand of Olearia hectori, a deciduous tree daisy, which Sir Peter calls “quite a little treasure trove.” The responsibility of looking after the fragrant flowering trees, however, is something they’re too busy to take on, so, in a precedent-setting agreement, the QEII Trust will cooperate with the Department of Conservation to manage the stand.

The Elworthys already have their hands full carrying out their role as custodians of other covenanted areas. Lady Fiona shows me what they’re protecting in a place of limestone caves and cliffs they call the Valley of the Moa: pre-European Maori rock paintings of moa, other animals, and human and supernatural figures.

“We’re looking at the temporary homes of people who visited this valley annually,” she says. “We’ve found stone tools, and the shells of both cooked and raw moa eggs. Moas were here in big numbers, grazing and browsing these hills. We’ve found bones everywhere. Sometimes they would get stuck in that swamp over there, and giant eagles swooped down on them with their talons.”

It was Lady Fiona’s idea to covenant this sheltered valley, which, in addition to the wonders within, enjoys a view to Aoraki/Mt Cook in the far distance. “In another hundred years, how many areas like this will be left, half an hour from Timaru?” she asks. “It took three-and-ahalf years before all four of our children agreed to the covenant, which prohibits any house site here.”

Another covenant at Craigmore protects a cave with a clear charcoal-andochre rendition of what is conceivably a giant Harpagornis eagle, its wings outstretched. The Elworthys have built a track down the hillside to the cave and planted cabbage trees and native shrubs to enhance the landscape. Locals often bring their homestay guests to have a look. “It’s quite a challenge,” says Lady Fiona. “Every day in summer we get requests to see the rock art. People could look all day in the Valley of the Moa and still not find the caves without a guide.”

The Elworthys are glad to have QEII covenants to protect these rare sites. “Covenanting was a trailblazing idea back when we started,” notes Lady Fiona.“Now it’s become mainstream.”

To Sir Peter, a former chairman of Federated Farmers and of the QEII Trust board of directors, the success of the trust is no surprise. “Most farmers, along with their wives and partners, are conservationists, but they’re suspicious of government departments. QEII gives farmers a wonderful opportunity to work in partnership with a non-governmental department, get a contribution to the cost of fencing and work with a board made up of farmer members. Landowners invest a lot of time and money caring for their land, so they like the idea of protection in perpetuity.”

[Chapter break]

A covenant protecting Aroha Island, near Kerikeri, has as its focus the preservation of no less a creature than the national bird. Colin and Margaret Little gifted the island to the QEII Trust after looking after it themselves for 20 years. “This place is protected forever in a developing world,” says Greg Blunden, QEII’s regional rep for the Far North and joint manager, with his wife, Gay, of the island.

The trust runs an education centre, camping area and guest cottage on the island, visited annually by 5000 people who want to see kiwi in their native environment. “The New Zealand Kiwi Foundation grew out of here, and that wouldn’t have happened without the trust’s help,” Greg says. “We’re helping private landowners manage their land to protect kiwi, with integrated predator management for rats, mustelids, feral cats, dogs, rats, possums and pigs. In any area not managed, the birds disappear.”

On Aroha Island kiwi are thriving, as visitors discover when they take a night-time walk. The telltale rustling of foliage and the crack of snapping twigs can be heard in the undergrowth as the whiskered birds pace about, tapping and sniffing for worms. A male kiwi’s shrill, penetrating call, described by 19th-century ornithologist Walter Buller as “half whistle, half scream,” pierces the rhythmic slap of the tide in the mangroves.

The key to kiwi recovery in New Zealand, Gay tells me, is the survival of chicks against the depredations of stoats and other predators. She is raising two shaggy-coated youngsters, hatched from eggs found by loggers in nearby Waitangi Forest. “It’s a real joy to raise the babies past the vulnerability stage,” she says as she pulls a sleepy nestling from its burrow-like box to weigh it. “It’s very satisfying to know there’s one you got through safely.”

A few hours’ drive from Nelson, another public education centre is being set up with the help of a QEII covenant, this one to teach people about the importance of New Zealand’s remaining wetlands. The Auckland-based New Zealand Native Forests Restoration Trust recently purchased the largest wetland in the northern part of the South Island: Mangarakau Swamp, in north-west Nelson. City-dwellers who may well never lay eyes on the place contributed to its purchase. The ink was barely dry on the deed when a covenant was signed.

“This is an astonishing piece of landscape,” says project coordinator Jock Lee. “It’s remarkably intact in spite of efforts over the years to change it.”

The swamp is a breeding ground for native fish, including mudfish, kokopu and inanga. Secretive Australian brown bitterns nest in the raupo at its edge, and orchids grow in the surrounding regenerating forest, where 300 different native plant species have been identified. “Now that grazing has been stopped, you can start to see what the natural regeneration will bequeath to our grandchildren,” says Jock.

The flax growing prolifically around the edges was once prized by Maori tribes who came regularly to gather the harakeke for weaving, he explains, adding, “We’d like to rekindle that interest.” He is full of praise for QEII covenanting. “It’s a fantastic method of protection. It’s simple for the landowner, and it’s flexible.” And it’s not just for farmers, he adds. “Even in the cities, New Zealanders feel they are protectors of the land, with a sense of guardianship.”

Corporations, too, are jumping on the QEII bandwagon—much to the relief of New Zealand’s “dinosaur lady,” Joan Wiffen. A self-described “common garden-variety housewife,” Joan has spent the past 30 years exploring the rocky Mangahouanga Stream, deep in the remote Urewera Range.

Having discovered many fossils there—proving what scientists had previously refused to believe, that dinosaurs reigned in New Zealand for 15 million years in the late Cretaceous period—she has re-written the country’s palaeontological history.

Now 81, she and other members of the Hawke’s Bay Palaeontological Research Group are still whacking Mangahouanga rocks with hammers. They have unearthed the bones of ankylosaurs, carnosaurs, sauropods and pterosaurs, as well as of marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. “It’s a unique site,” Joan says, showing me a fossil inside a bowling-ball-sized boulder she hauled out on a recent trip. “It’s the only place in New Zealand where dinosaur bones have been collected.”

The stream and its fossil treasures, now surrounded by a vast expanse of plantation pine forest, will be permanently protected under a QEII covenant signed by Carter Holt Harvey Forests. “I’ve nagged the property owners for 20 years about a covenant,” Joan tells me. “It’s very fragile pumice-ash country, and without protection it could be obliterated by the forestry work. The original members of our fossil team are getting pretty ancient, and we probably won’t be around to look after it too much longer. With the covenant, it will be retained like an oasis in the middle of the desert.”

Hawke’s Bay Palaeontological Research Group are still whacking Mangahouanga rocks with hammers. They have unearthed the bones of ankylosaurs, carnosaurs, sauropods and pterosaurs, as well as of marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. “It’s a unique site,” Joan says, showing me a fossil inside bowling-ball-sized

boulder she hauled out on a recent trip. “It’s the only place in New Zealand where dinosaur bones have been collected.”

The stream and its fossil treasures, now surrounded by a vast expanse of plantation pine forest, will be permanently protected under a QEII covenant signed by Carter Holt Harvey Forests. “I’ve nagged the property owners for 20 years about a covenant,” Joan tells me. “It’s very fragile pumice-ash country, and without protection it could be obliterated by the forestry work. The original members of our fossil team are getting pretty ancient, and we probably won’t be around to look after it too much longer. With the covenant, it will be retained like an oasis in the middle of the desert.”

For Carter Holt Harvey, entering into the covenant was consistent with the process of forest certification through which timber companies seek to demonstrate that they manage their resources sustainable and with concern for the environment. “We need to show we understand how best to manage our indigenous reserves,” says Robin Black, Carter Holt Harvey’s environmental planner. “It seemed appropriate to go with a QEII covenant because of the credibility and impartiality of QEII.”

Local and regional councils are also finding QEII covenants useful in fulfilling their legal obligations under the Resource Management Act for managing significant natural features. Even small landholders are covenanting their special rock outcrop or wetland. Some are joining up with their neighbours to protect a healthy stream or native forest remnant that crosses property boundaries.

“The work of the trust has been quietly growing in importance over the past 25 years,” says the organisation’s chief executive, Margaret McKee. “More than 75,000 hectares of land is under QEII covenants, but there remains 16 million hectares of New Zealand’s rural land in private ownership. So there is still enormous potential for further growth.”

Having the QEII Trust as a working partner is helping landholders all around the country with their nature-restoration projects, as I’ve discovered along my journey. Complex ecological issues are discussed in friendly chats over cups of tea with the trust’s regional reps, such as botanist Miles Giller, who are treated almost like members of the family.

“We don’t achieve conservation through beating our chests or shaking our fists,” Miles explains. “The answer is in having everybody see themselves as an environmental manager.”

Why are QEII covenantors so willing to take on that responsibility? For Miles, the answer is simple: “It’s just the love of it. It’s an inner calling.”

Twenty-five years ago, Gordon Stephenson never imagined the trust act’s potential to meet the needs of councils, urban-based conservation groups and corporations. With covenants designed to endure in perpetuity, it is fortunate that the concept is flexible enough to adapt and evolve along with public attitudes.

Today, in his patch of prized bush where the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust first took root, years of predator trapping and poisoning are paying off. North Island robins have been reintroduced, and are now able to hatch and rear their young in safety. The dawn chorus is growing louder, too, just as it is in every covenanted area where owner– managers are nurturing their land back to its former health.

Piece by piece, QEII covenants are weaving a munificent quilt of New Zealand biodiversity and natural open space, stitched together by the simple strength of people’s love of the land.