The mechanical sympathy

Bruce McLaren founded the most successful Formula One team in history and set records that lasted decades. His name is still emblazoned on some of the world’s fastest cars. But the fairytale quality of McLaren’s life—growing up above his parents’ petrol station, racing the Austin 7 he built as a teenager, later winning Monaco and Le Mans—conceals the hardships he overcame and the innovations he made. McLaren didn’t just race cars, he designed and built them, and in doing so, transformed the sport of Formula One.

It’s December 12, 1959, a warm Florida day with a gusty breeze. Eighteen Formula One cars line up at the starting blocks at Sebring, a track repurposed from the runways of a combat flight school where United States Air Force pilots on their way to World War II learned to fly heavy bombers.

Cones and sandbanks mark the track, through airfields still scattered with ageing aircraft and spare parts. It’s dry, flat and barren. The crowd isn’t much better.

From the fourth row of cars, Bruce McLaren can see the stands, sparse with spectators. Most people are watching from grass berms by the edge of the track. Some lean over the steel guard railings lining the home straight.

It’s the first time a Formula One Grand Prix has been held at the Sebring International Raceway. It’ll also be the last.

In front of McLaren is Australian driver Jack Brabham, once his idol, now his team-mate. ‘Black Jack’ Brabham is known for his exuberance and quick judgment, and he’s a competent racing strategist in his own right. He’s leading the points table, with enough to win the drivers’ championship, as long as he holds off Stirling Moss, who’s in pole position.

McLaren runs his mind over the track, nervous about conditions that might make it dangerous. Oil spills. Recent rain. Sebring is renowned for being rough, the concrete hammered over the years by novice pilots landing B-29 Superfortresses.

He turns his attention to his Cooper T51. Does he know the car well enough? Were there any changes he made between the last practice and the race? Could the car break? Or blow up? Will he get hurt? Four drivers were killed in the 1958 Formula One season—an unprecedented number.

The flag falls and Moss has the lead, surging ahead of Brabham. But on lap five, Brabham looks up to see ‘P1’ on the pit board. Moss, in ‘position one’, is forced to retire from the race. His gearbox has failed. Brabham takes the lead, followed by McLaren and French driver Maurice Trintignant.

McLaren is driving well, so he’s calm. He’s calm, so he’s driving well. One thing goes with the other. The best races are the ones where he doesn’t concentrate, when everything happens automatically. Sometimes he’ll look up mid-race to read ‘10 more laps’ and think to himself, “My word, that’s gone quickly.”

He isn’t thinking about when to brake or when to turn or when to apply the throttle. It’s as automatic as the motion of his hands shaping words when he writes a letter.

Brabham, in first place, is feeling confident. His tyres have plenty of rubber left. He hasn’t pushed the car especially hard. The sun is shining and the engine is barking away behind his shoulders. The white flag waves, and Brabham nods to team owner John Cooper as he passes the pit. One lap to go, and the race—and the drivers’ championship—are within Brabham’s grasp.

Then his engine drops to two cylinders, starts to splutter, dies. Brabham has run out of petrol. He’s 365 metres from the finish line.

McLaren is so startled, he almost crashes into the back of his mentor. He takes his foot off the throttle and slows down—should he stop to help? Brabham frantically waves him past.

“Get on with it! Go for the flag.”

McLaren jams his foot down and charges ahead, but Trintignant has profited from his hesitation to bite into his lead. There are only two corners left and then McLaren and Trintignant are flat out down the home straight. McLaren holds his advantage—just. He passes the checkered flag six-tenths of a second ahead of Trintignant.

His Cooper rolls to a stop and the crowd storms the track. He emerges from his unthinking state to find hands patting him on the back, voices congratulating him. He barely registers the sight of Brabham pushing his car across the finish line to take fourth place. All of a sudden, he’s standing on a dais, wreaths around his neck, lifting the United States Grand Prix trophy above his head.

McLaren is 22 years and 104 days old. He’s the youngest-ever driver to win a Grand Prix. It is a record that will stand for more than 40 years.

[Chapter Break]

When McLaren was young, his family lived atop a Spanish Mission-style service station in Remuera, east Auckland. Upstairs was a cramped two-bedroom apartment and downstairs were six pumps and a small workshop. McLaren often wandered down to the garage floor to be in the thick of the grease and grime. When tools went missing, everyone knew who to blame. Once, he told his mum, Ruth, that a fantail said he’d become a race car driver.

McLaren was nine when he began to limp. His body had cut off the blood supply to the top of his femur—a rare childhood condition called Perthes disease. He was sent to the Wilson Home for Crippled Children in Takapuna, where he lay for months on end, legs encased in plaster, strapped down to a bed with bicycle wheels called a Bradford Frame.

McLaren soon realised he could reach the wheels. He and the other patients, most of whom were recovering from polio, began to shuttle themselves around the home’s grounds.

“The outcome was inevitable,” he recalled.

One night, bored, he suggested a race around the corridors. There were crashes and bumps and scrapes but “nothing drastic ever happened”, he said.

That was until they decided to explore the grounds via the home’s various ramps. The group pushed off, going down the first slope, gathering speed. Then came the second ramp. At the end of it was a “slow right-hander”. There was no way the entourage would make it around. So they went straight. McLaren’s frame “whistled” off its bed base and launched him feet first into a flower bed. It was never the same again.

After two years in the Wilson Home, McLaren had to learn to walk again, and he started high school on crutches. His left leg had become slightly shorter than his right, resulting in the limp he would carry for the rest of his life.

When McLaren returned home, his dad, Les, bought him a car, a 1929 Austin 7 Ulster. It came in pieces but cost only $110. Together they built it: an open-topped, spoke-wheeled, chrome-grilled, red racing model. Les planned to sell it for a profit. His son had other ideas. He set up a simple figure-eight racetrack around the fruit trees on the family section. There was a hard-lock turn around the clothes line and the plum tree, then a hairpin around the lemon tree, and back up past the garage. It was a cheap thrill, but he loved it.

He could flog petrol from the family garage, and he worked on the car constantly, adding his own modifications. He fitted it with a new steering wheel, then hand-painted optimal gear-change points on the speedometer, effectively adding more than 15 kilometres per hour to its top speed.

Granted, it could do only 110 kilometres per hour flat out.

“But at that time, it was probably enough, and with that particular car, it was probably dangerous enough too,” he said.

Les entered the Austin 7 in a hill-climb race at Muriwai Beach, but fell sick. Fifteen-year-old Bruce took his place in the driver’s seat.

The dust rose from the Austin’s thin wheels, no wider than a hand. It was an unsealed track, narrow and windy, with steep drop-offs and an unbroken view of the ocean. McLaren was more excited than he had ever been in his life. At the top of the hill, he learned what it felt like to win.

It was the shortest, slowest race he would ever compete in, with the least prize money—none—but he later said he always felt a connection between the Muriwai hill and the grandest stages of motor-racing.

“It is just a game, only played on a bigger scale,” he said. “And hopefully the little problems and the little joys of the 15-year-old have become much bigger problems and bigger joys.”

McLaren graduated from the Austin 7 to a Ford 10 Special, then a Healey, then a bob-tailed Cooper-Climax. He raced at local gymkhanas, and at Ardmore Airfield in South Auckland.

After a stint at a technical college, he enrolled in an engineering degree. It was short-lived.

At 20, he was sent to Europe as part of a new scheme to give promising New Zealand drivers a shot at the big league. His University of Auckland report card was truncated by a simple statement: “Went motor-racing.”

[Chapter Break]

Before Sebring, McLaren was an unknown. Now, he’d earned his place on the Formula One circuit. At 23, he won the Argentine Grand Prix with the Cooper team. He took second place at Monaco, Spa and Oporto. A third at Rheims, a fourth at Silverstone.

“He has out-driven and outclassed all other drivers in the game except Brabham,” wrote a reporter of his exploits.

But McLaren and Brabham were becoming frustrated at the development of the Cooper team. Despite Brabham claiming his second successive world title and Cooper winning the factory championship, Brabham broke away to develop his own team. McLaren started to think about venturing out, too.

He’d been busy designing his own car. He made sketch after sketch, complete with detailed notes on internal combustion and aerodynamics in his squat, scratchy handwriting. There were diagrams of chicanes from tracks he had raced, modifications he wanted to make to engines and braking systems. He outlined a company structure, made notes to himself of the type of people to employ. He listed his successes and failures and how his young family was getting on.

“It was never just the racing that McLaren longed for,” wrote biographer Richard Becht. “It was the complete picture.”

McLaren’s fascination with cars was derived from working on them, from understanding them. Becht called it “the mechanical sympathy”.

McLaren wanted to take that sympathy into his own world where he was in control. He called it “the start of something big”.

[Chapter Break]

“I don’t have much idea of business, as you know,” wrote McLaren to a prospective investor.

He founded Bruce McLaren Racing in 1963, at the age of 26. His wife Patty McLaren and friend Eoin Young were co-directors, and they leased a small factory in southwest London.

One of McLaren’s first employees, Howden Ganley, a New Zealand driver and mechanic, said it was the most basic workshop he’d ever seen.

The McLaren factory was in fact a concrete prefab building full of earthmoving equipment. The only clear space had a dirt floor, as the concrete had disintegrated under the weight of bulldozers.

“Against one wall there was a workbench, approximately eight feet long,” recalled Ganley. “Equipment consisted of a small drill press, a bench vice, and a set of oxyacetylene welding bottles with in-line gas fluxer. There were no chassis stands, but there was a large wooden crate that served the same purpose.”

McLaren was contracted to build two Coopers for the following year’s Tasman Series. He would use the suspension and steering components of Formula One vehicles but narrow and lighten the chassis. There was no bureaucracy requiring him to get official designers on board—they just sketched and built as they went.

By the New Zealand Grand Prix in 1964, the McLaren team had their two ‘specials’. McLaren lined up at Pukekohe against Jack Brabham, and this time they were rivals. His new creation held up, beating fellow New Zealander Denny Hulme, in second place, by four seconds. McLaren’s other car came third. Brabham retired from the race.

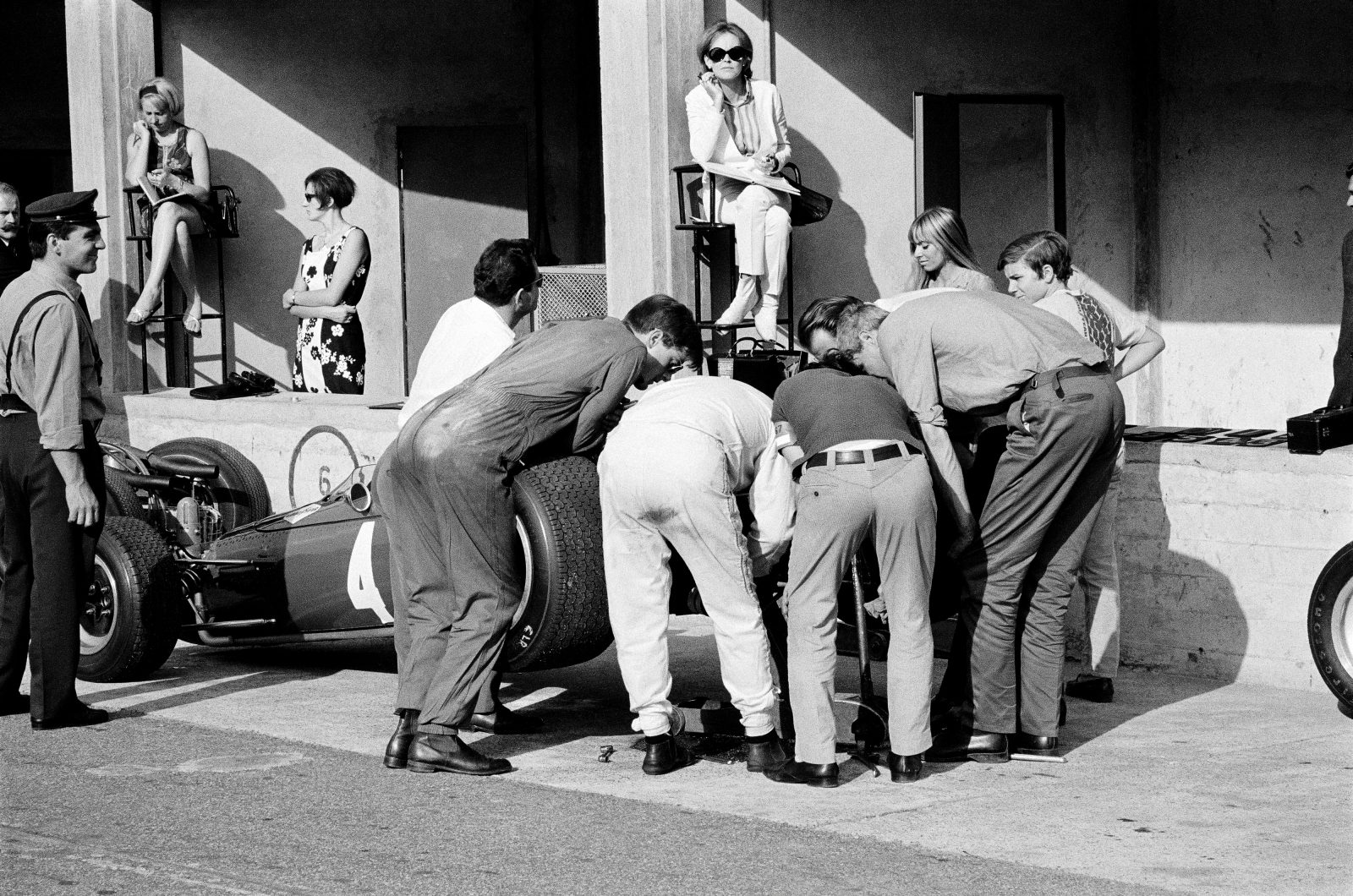

Soon, the McLaren factory was decorated with large framed photographs of drivers adorned with winners’ wreaths, grinning down past the low-hanging lights at engineers hunched over workbenches. Car frames were strewn across the floor. There were scale models of proposed racing designs, new incarnations of radiators and transmissions.

The same year, the team were testing at the Goodwood Circuit in West Sussex when a mechanic became tired of removing the front section of the body to check the fluid levels of the brake and clutch. Instead, he cut a small area at the top for access to the fluid cylinders, and covered the hole with a flap.

On the next test run, McLaren noticed air pressure lifting the flap rather than pushing it down—the opposite of what they’d assumed would happen. Instead, the hole rerouted hot air, helping to exhaust it from the radiator.

McLaren pulled into the pit, and another mechanic picked up a pair of shears and cut a large square hole in the top of the body, folding it down behind the radiator to deflect air upwards. On the next run, the car seemed to grip the track better.

The holes looked like nostrils, and they became a defining characteristic of McLaren cars for years to come.

“It seemed every day some new project or idea came from Bruce,” said Ganley, who quickly progressed from workshop gopher to fabricator. “He would bustle into the workshop in the morning with his yellow legal pad covered in sketches made the previous evening.”

McLaren made the rounds of each employee, congratulating and encouraging them in their work, then introducing the next idea.

“Every team member was encouraged to lift their game constantly, to strive to do more, and everyone wanted to be the best,” said Ganley. “It was all for Bruce.”

[Chapter Break]

“To win a race now is not only to do the job properly from the driver’s angle,” said McLaren. “It means that we have beaten other teams, other constructors, and very often we’re going against what we feel are bigger and more-supported teams. This is very thrilling.”

In the mid-1960s, McLaren’s attention shifted to the world of Can-Am racing. The series took place in Canada and the United States, and was known as an arena that permitted almost anything design-wise— unlimited engine sizes and virtually unrestricted aerodynamics—as long as it made cars faster. It was the place McLaren thought he could push his vision to the limits.

He’d already created the fastest Formula One cars on the planet. Now, he’d build 600-horsepower monsters.

By his second year of participation in Can-Am, the McLaren team won five out of six races. In 1967, they won all 11.

“How is it that inside a decade, New Zealand drivers have come so far in this fiercely competitive business?” asked a British reporter in 1968. “Whatever the future holds for McLaren, he has made his mark. He is recognised not only as one of the most able and successful people in the business but also as one of the most pleasant and unassuming.”

For Howden Ganley, the answer was obvious: McLaren was a gifted leader.

“It has always been my view that had Bruce come in the workshop one day and said, ‘Men, today we are not going to work on the cars, we are going to march across the Sahara Desert,’ there would have been total support along the lines of, ‘Okay, Bruce. If that’s what you think we should do, then that is what we will do.’ His men would have followed him anywhere. I know I would.”

McLaren came to symbolise an understated New Zealand way of being: passionate about his work, humble about his achievements. His charisma was defined by a soft-spokenness that demanded respect, reminding many of another famous New Zealander: Edmund Hillary.

Hillary’s father and McLaren’s father were friends, and would recount their sons’ achievements to each other over the phone. Bruce won Le Mans. Ed reached the South Pole.

McLaren was starting to think about retirement—but he first wanted to gain a reputation for running a racing team. He would retire, he said, when he finally felt that he was not as young as he used to be.

“I can’t put a time thing on it,” he said. “Ever since I’ve been 20 years old, I’ve said I’ll stop racing in three or four years.”

[Chapter Break]

There are adverse cambers on the Goodwood Circuit. There are double apexes and slight undulations in unexpected places. The 3.8-kilometre track is famous for keeping drivers busy and throwing cars about without a moment’s respite. If a car handles well at Goodwood, it’ll hold up anywhere.

In 1970, the Can-Am series was looming, and the McLaren team had just made their debut in the Indianapolis 500. They weren’t as successful as hoped, but there was no time to dwell.

McLaren needed to get back to testing the new M8D car ahead of the first Can-Am race. Which brought him to Goodwood on a summer’s day: June 2, 1970. Not long after noon, he set out from the pits. The previous month he had tested the same car on that same track. “500 miles trouble free,” he wrote.

As McLaren accelerated hard out of the Lavant corner, a pin missing from the tail section of the car loosened the body. The wind pressure ripped the rear bodywork off the car, removing all downforce and with it all stability. The M8D spun, left the track and slid into a post at 160 kilometres per hour.

Nobody saw it. There was noise and then smoke. McLaren was pronounced dead at 12.22pm.

He’d once called his life’s dedication “the cruel sport”. When teammate Timmy Mayer was killed in an accident, McLaren wrote an epitaph that could have been his own: “The news that he had died instantly was a terrible shock to all of us, but who is to say that he had not seen more, done more and learned more in his few years than many people do in a lifetime? To do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy. It would be a waste of life to do nothing with one’s ability, for I feel that life is measured in achievement, not in years alone.”

The team would carry on with the Can-Am season, said McLaren racing director Phil Kerr.

“How would Bruce have felt after all the hard work he had put into the organisation, that we just gave it away like that?”

Kerr knew the team were capable of building soundly engineered cars—but from now on they would not have McLaren’s inspired touch.

“This means we will have to work harder to build the same sort of car,” said Kerr. “But we will.”

Twelve days after McLaren’s death, Denny Hulme—though his hands were still healing from burns—insisted on getting behind the wheel for the first Can-Am race of 1970. Joining him was American driver Dan Gurney. The pair took first and third. Of the 10 races in that year’s series, McLaren drivers won nine. The following year they did the same, demolishing the opposition. Three years later, they took both the drivers’ and manufacturers’ championships of the 1974 Formula One. The team became one of the most successful in the history of motor-racing.

“Such was the strength and depth of Bruce’s organisation that it was able to not only survive the loss of its founder, but after the blow, it regrouped and went on to achieve many of the ambitions and goals that Bruce had set,” said Howden Ganley.

Bruce McLaren’s epitaph does not dwell on his races, his trophies, or the moments spent on podiums around the world. He represented more than that: a certain spirit, an understated ambition, executed with passion, good humour and humility. Etched onto a black marble memorial stone at Goodwood is a simple message: “Engineer, constructor, champion and friend.”