The hard road

The tourism potential of Fiordland’s Milford Sound was recognised in the late 1800s. The problem was getting there. Pushing a road across the Main Divide was feasible, but between the headwaters of the Hollyford and Cleddau valleys was an almost-sheer 500 metre granite wall. The Homer Tunnel, 20 years in the making, provided the solution, and today visitors emerging from the Cleddau portal descend a sealed slalom that offers few clues as to the difficulty of building or maintaining a road in such precipitous country.

A thousand metres below me a bus grinds its way up the Milford road. From my vantage point on the side of Mt Talbot it looks like a Matchbox toy. With my thumb and forefinger I could pick it up, like King Kong. If I were to yell, sightseers on the road would be able to hear me, but to reach my perch would take them hours of difficult climbing. The bus driver changes down again and lines up his vehicle for the entrance to the Homer Tunnel. With a magician’s ease, the bus disappears into the side of the mountain.

The bus, bringing tourists to Milford Sound, has taken a couple of hours to travel from Te Anau to here, and its passengers will visit the area for only a few hours. I’m hoping my own journeys along the Milford road will never end. Certainly, to experience the mountains and the many wonders radiating off the road would take a lifetime. But recently I have become aware of a family connection to the road, and in particular the tunnel. As I get older, I find that such personal connections give me a great sense of belonging—to Milford, to Fiordland and to the whole of New edges blend together at the far end of the valley, drawing the traveller on towards the heart of the Fiordland mountains.

Beyond the Eglinton, the road passes several small lakes which fill depressions left by glaciers that melted 10,000 years ago. You need to encounter these lakes several times to experience their different moods. When the sun is making diamond patterns on their surfaces, speeding past seems like a crime. But when a gale rips down the valley, with the wind lashing the steely black water, this is no place to linger.

Past the lakes, the road sweeps over the Divide and deposits you on the West Coast. At the Divide, the mountains stun the imagination. To drive through this pantheon of peaks is to be profoundly humbled. The steep Marian hill forces your car into second gear—which is just as well, because the sight of the near-vertical wall of Mt Christina directly in front has been known to cause erratic driving.

The road continues beside the Hollyford River, at the bottom of one of the grandest glacier-carved gullies onearth, until emerging into the subalpine zone of the upperHollyford valley. To be given access so easily to this wild valley is a great gift, and a walk up the Gertrude valley is an incomparably inspiring way of easing driver’s cramp. Take a stroll in the Gertrude and you’ll want to throw away your car air-freshener in exchange for the memory of the scent of wildflowers and alpine air.

Back on the road, escape from the cirque seems impossible, but the next bend in the road reveals the entrance to the Homer Tunnel. Driving through the dripping blackness, broken only by headlights, is a way of refreshing overloaded visual senses before bursting out into the Cleddau valley.

Be prepared. If you’re an unbeliever, the view from the portal down the valley may bring you to your knees. The rest of the journey to Milford Sound is through smothering West Coast rainforest, with glimpses of side valleys that are mostly untracked wilderness. Mitre Peak is usually the mountain to look for, although it is a mountain whose soul has been stolen through being photographed too much. Mt Tutoko is much more incredible, a bulky glaciated peak rising from the head of the Tutoko valley, at 300 m, in one grand sweep of granite and ice to a 2723 m summit.

From go to whoa the Milford road is 119 km long, and it is the only stretch of tar seal in Fiordland National Park. Fiordland itself is part of Te Wahipounamu (“the place of greenstone”), which was listed as a United Nations World Heritage area in 1990.

The area’s Maori name refers to the fact that pounamu was collected from Milford, and sections of what is now the modern road were probably used during those expeditions. Europeans were quick to appreciate the area’s scenic value. As early as 1891, Milford Sound was considered a tourist destination, and a more direct route (other than the now-famous track through the mountains) was sought, with the goal of forging a road link. A local explorer, Henry Homer, who owned land at Jamestown, in the Hollyford valley, teamed up with George Barber to look for such a route in the upper Hollyford.

Homer and Barber traced the Hollyford River to its source and discovered the saddle which now bears Homer’s name. It is a rock wall which the glaciers and the Maori god Rum failed to breach. Legend tells us that Rum hacked at the bottom instead of the top, and failed in his effort to wear the saddle down.

If Homer was hoping for an easy route down the other side to Milford Sound, he would have been disappointed. The Cleddau side of the wall is so steep that a granite boulder trundled over the edge would hardly bounce before exploding on the valley floor. To better nature—and the gods—is no easy task, but Homer thought laterally and proposed a tunnel to link the Hollyford and Cleddau valleys.

His vision wasn’t shared by others, especially not E. H. Wilmot, a government surveyor who accompanied Homer to the saddle later that year and burst his bubble by saying, “It is quite useless for a route to Milford.”

But you don’t explore in Fiordland without having a certain amount of stubbornness, and Homer didn’t give up. He wrote to the Wakatip Mail: “No timber wanted, no climbing over ice and snow; no repairs and open all the year round. The size of the tunnel 7 ft 6 ins high by 6 ft wide, at say 1 pound-15 shillings a foot to a total of 2100 pounds. This should open a good horse track all through. A party can be found to accept the work at the figures tomorrow—and be glad of the chance.”

A third opinion was sought in 1890 from R. W. Holmes, the district engineer in Wellington. He reported that a tunnel 8 ft high by 6 ft wide could be put through Homer Saddle for 2000 pounds. Half a century later, when the tunnel was eventually constructed, the cost came to over half a million pounds. William Henry Homer never saw the inside of Homer Saddle via his tunnel. He died in the summer of 1894.

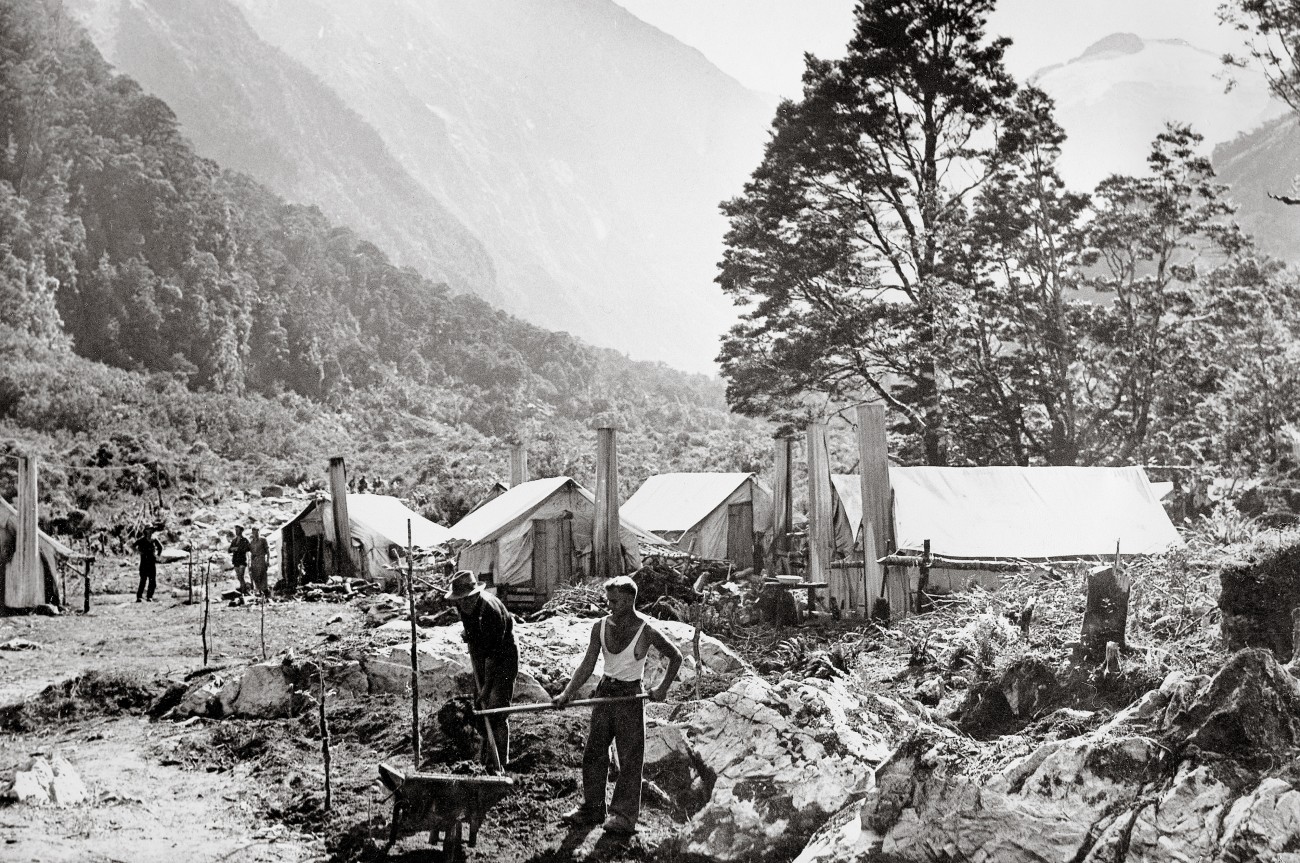

The Milford road concept, once approved promptly stalled until the Great Depression, at which time the government used the building of the tunnel and the road as a relief project to keep men in employment. Construction of the road began from Te Anau in 1929, with 200 men using picks, shovels and wooden wheelbarrows. My grandfather, Bert Tecofsky, was one of those men, and he worked on the tunnel for six months, until the Second World War suspended work in 1942. He used to write every week to my grandmother, but none of those letters have survived. Here I have tried to recreate one based on conversations with my grandmother. It gives some idea what it was like living in that alpine arena.

Dear Harriet, Thank you for the bag of coal. My but is cosy and the cockles of my heart are warm from the thought of you sending it. I use it sparingly and stack green logs either side. This makes the fire smoke, but saves fuel. When the nor’wester blows, the wind comes down the chimney and smoke puffs into the room. Still, better a cloud of coal smoke from a warm fire than a cloud of cold smoke from my mouth.

An unfortunate thing happened yesterday. A kea thought he would perform surgery on my truck seat. He had made some nice incisions and was busy ripping the innards out when I came back from smoko. I saw red and hurled a rock at him. Only wanted to scare him but he fell off his perch, like that budgie we once had. “Oh dear,” I said. “Sorry,” I said. I picked him up and gave him a shake, but he was dead. His parting flight was with my help, a not very graceful fling into the bush. A damn shame and the shocked look on his face still haunts me.

The full water bucket is sitting beside the fire like a cat. I have to bring it inside, otherwise in the morning it is a block of ice. Temperatures have been well below freezing for a few weeks now. Frost flowers have been growing in the bush, amazing thick carpets of ice that tinkle when you walk through them. I’d pick one and send it to you but it would melt. The cold isn’t all grim, and the snow can be fun. A few of us went out sledging yesterday with a piece of corrugated iron with one end turned up. I haven’t laughed so much in ages.

I’m off over to the Milford side for a spot of bulldozer driving so don’t come and visit until I’m back at the Homer. The Cleddau is damp and the huts aren’t as substantial as this one, with its corrugated iron roof. Which reminds me, have to nail that sledge back on tonight. Thanks again for the coal and warm cockles. Give the girls a hug from me.

[chapter break]

I descend Mt Talbot to the road and walk down to the Works Infrastructure building called the Chapel. This was the site of the Homer Camp, where my grandfather lived. Walking through stunted trees beside the road I stumble across rusting pieces of corrugated iron and bits of wooden floor rotting in harmony beside a dead tree stump. A battered chimney pokes out from a pile of rocks. I pause here and think of my grandfather, perhaps sitting in a small but at the base of this chimney cooking his tea.

As my car warms up at the Chapel, I hear a rumbling sound. I scan the surrounding walls for the source of the noise. At the head of the McPherson cirque a puff of white near the lip of the 1000 m bluff grows into a cloud, and an avalanche booms into the valley. My instincts say run, but a fascination for avalanches holds me fast. Billowing snow hurtles towards me, looking deceptively gentle. When I realise the snow won’t reach me I leap around punching the air, cheering the power of nature. I am safe, but in 1936 a road worker was killed by an avalanche, and in 1937 two more men died outside the tunnel.

Usually only the deaths make the papers, but at least 15 other workers have been seriously injured in avalanches on the road. One was hurled 400 m by wind blast, yet suffered only a disclocated shoulder.

From 1954 until the 1970s, the road was closed in the winter on account of the avalanche danger. Then, in 1977, tourism and fishing interests lobbied successfully for the road to be kept open year round.

Six years later—on September 23, 1983—Pop Andrews, the road-maintenance supervisor, and Wayne Carran, a young machine operator, were on the Cleddau side of the tunnel clearing debris from an avalanche. In hindsight, Carran says they shouldn’t have been there as the risk of another large avalanche hitting the road was high. However, knowledge of avalanches wasn’t as great then as it is today, and avalanche activity through the 1970s appears to have been less than average, and was certainly much less than during 1930-50. The level of hazard was underestimated.

Carran recalls that earlier, as the two men had driven up the road, Andrews’ body language had betrayed a certain nervousness about entering the avalanche zone. But his intuition regarding the danger was dulled by the pressure coming from various quarters to reopen the road. Tourists were trapped in Milford. The road had to be cleared.

As the snowstorm continued, men and bulldozer made puny swipes at the huge pile of debris, a painfully slow job. High above them, the weight of new snow yielded to gravity, a fracture line opened up and thousands of tonnes of snow hurtled into the valley.

Andrews yelled a warning. Carran ducked down behind the dash of the bulldozer, while his boss sought shelter behind the machine. Then the avalanche roared into them. The wind blast picked up the 14-tonne machine, flipped it on its back and shunted it 70 m down the road.

Carran climbed through a window in the cab and spent three-quarters of an hour trying to find Andrews, digging with his bare hands through avalanche debris that had set like concrete. When he found him, Andrews was dead—probably crushed by the bulldozer.

After Andrews’ death, Carran was instrumental in setting up an avalanche-control programme to prevent such a tragedy happening again. He is now the supervisor for Works Infrastructure in Te Anau, and has worked on the road for 20 years. When I asked him if he thought fate had chosen him for the job, he replied matter-of-factly, “No one else stepped forward, so I did.”

Carran is a stocky man in his late 40s, with a bald patch that looks like an avalanche path swept clean of vegetation. The word “stress” isn’t in his vocabulary. He says he tends to slide down under the pressure at times, like diving in the ocean, only to surface refreshed. He tends to see life in black-and-white terms, not as a complicated kaleidoscope—an attitude that flows over to avalanches. When he thinks about them he closes his eyes, focusing on their weaknesses.

“I was in a wreckers’ yard in Australia, and two Dobermans lined me up, one on either side. They were big and black with shiny teeth, looking for a piece of action. I figured that so long as I didn’t move or breathe I was all right. I was relieved when the owner came out.”

He likens avalanches to those dogs. If he respects their power, doesn’t make a wrong move at the wrong time and doesn’t turn his back on them, the hounds of hell won’t descend on him again.

Out of necessity, the Milford avalanche-forecasting programme has developed into one of the most advanced in the world, and when Carran talks about it he is visibly proud. Not just for the programme, but also his men.

The programme has a “zero tolerance for deaths from avalanches on the Milford road,” says Carran. It relies on accurate forecasting—being able to read the mood of the snow-pack and predict when it will avalanche—and active control—using explosive “bombs” to release avalanches before they occur naturally.

Bombs are made from a substance which looks like pink polystyrene ball-bearings–ammonium nitrate with diesel added. It comes ready-made in 25 kg sacks, and when a small amount of priming explosive, a detonator and safety fuse are added, you have a powerful device. Bombs are dropped out of a helicopter on to the suspect snow slope.

Passive control is also used, when, as Carran says, “things get too twitchy”—usually when the weather is too violent to allow flying or when being on the road to monitor avalanche activity is too dangerous. The road is closed, with locked gates at both ends, and humans submit to the greater power of nature. Nobody goes near the area until it clears and active control can be carried out, or the new snow has settled or avalanched.

[chapter break]

On a mellow winter’s day I join a group of Search and Rescue personnel outside the Chapel. Every year, training exercises are organised to practice rescue scenarios, just in case an avalanche buries a vehicle. Lloyd Matheson of the Te Anau police briefs us on the techniques we will be practising, and talks about the damage avalanches are capable of inflicting.

“Modern buses have a glass-topped roof great for seeing the mountains, but the wind-blast from an avalanche would blow them in,” he says. “It only takes 50 kpa pressure to break that glass. The wind-blast from an avalanche generates 5000 kpa pressure—enough to burst your eardrums.”

Avalanches are one of the most powerful and complex phenomena in nature, and those which occur in the vicinity of the Milford road are in the largest category of avalanche: class 5. A class 5 event can destroy a 40 ha forest and deposit 100,000 tonnes of debris in a valley.

Wayne Carran moves to the skid of a helicopter and tells us about a new search technique for avalanche victims who are wearing a transceiver. A transceiver is a beacon the size of a cigarette packet which emits a radio signal and locates other signals on the same frequency. During winter every worker on the road wears one, and the workers have competitions to see how fast they can find each other’s beacons. A fast time is under a minute.

When a large avalanche occurs, like the one in 1945 that destroyed a 100 m reinforced concrete extension, built to protect the east portal of the Homer Tunnel, the amount of debris produced is mountainous, and to search on foot is physically taxing and slow.

[sidebar-1]

Carran tapes a transceiver on a ski pole on to the helicopter’s skid and plugs an earphone cord into it. As he works he tells us that this method was developed specifically for the Milford road. The earphone is worn by the helicopter pilot, who makes the initial hasty search by flying over the debris.

On the exercise I ride in the helicopter with pilot Richard Hayes. Hayes swings from side to side of the imaginary debris, using his magic wand to pinpoint the strongest signal. Just before I start to feel airsick he lands with one skid on the steep slope and indicates for me to get out. I leap out into knee-deep snow with a transceiver and a shovel and complete a fine search. The dummy, with straw leaking out of his blue overalls, doesn’t look particularly grateful. He should be: it has taken only five minutes to find him, instead of an hour or more.

[chapter break]

Accurate forecasting is the key to keeping avalanches off the road—and ensuring that dummies are all that the rescue crews ever have to search for. Computer programs at the Works Infrastructure depot in Te Anau are used in conjunction with instruments and remote weather stations positioned in the mountains around the tunnel. These instruments have been either invented from scratch by Carran or fine-tuned from other applications, using a liberal dose of Kiwi ingenuity.

Being a mountaineer with a vested interest in staying alive when climbing in winter, I decide to visit the depot in Te Anau to glean more information. Wayne Carran’s wife, Ann, who monitors the weather and correlates all the data coming into the computers, ushers me into the room where an avalanche forecast is compiled every day during winter. Freshly painted walls and a squeaky clean floor remind me of a doctor’s surgery. As she talks, a squawking data logger spits out information. I am amazed to see the cold and lonely snowfield’s inner secrets projected onto a computer screen by a series of blips and lines.

“This line here indicates the temperatures as measured by a buried snow pole,” Carran explains. “The snow temperatures are zero Celsius near the bottom—that’s three metres below the surface—minus-10 in the middle and minus-15 at the surface. The temperatures tell us if there is a temperature gradient in the snow-pack which could promote the growth of crystals. Crystals are a potential sliding layer. More importantly, these readings tell us when the snow-pack has become isothermic—an equal temperature from surface to base. That’s when the snow is most stable. The Canadians had a similar device, but they couldn’t get it to work; the sensors kept freezing. Wayne bought a windsurfer mast and drilled holes down its length and put the sensors inside with small wires sticking out. Then he filled the whole thing up with expanding insulating foam. Works like a dream!”

While we are talking, Ian Wilkins, the avalanche-forecasting technician, crackles over the two-way radio. He is at 2000 m on Mt Belle, testing a new device which measures water percolating through the snow-pack.

Carran explains: “Its a domestic shower tray buried at the bottom of the snow-pack and tilted slightly. Underneath the plug hole is a tipping bucket—a small cup that is balanced. When a measured amount of water has dripped in, it tips. The water falls out and registers here.” Simple, but ingenious. But why do they need it, I ask?

“We have trouble predicting rain-on-snow events in the spring. The great thing about this device is it tells us how much water is filtering down through the snow-pack and if it’s coming out the bottom on the rock and not lubricating an ice layer.”

A few days later I feel I couldn’t be in safer hands as I accompany Wilkins back up the road when he goes to “stick his nose in the snow”—his term for physically checking the conditions.

“It’s important to not rely on machines,” he says. “You need to use all your senses for working out when a slope might avalanche. Intuition goes a long way. All the instruments might be saying things are fine and your guts will be churning. That’s when it can be time to close the road.”

We drive past the Hollyford turn-off and pass below cloud-capped Mt Christina. Black walls devoid of snow tower up into mist that appears welded to the mountain. Up there is the start zone of the Gates path, a cold, south-facing snowfield where some of the largest avalanches are nurtured by westerly winds screaming across the mountains from the Tasman Sea.

“Nineteen ninety-four was a legendary winter,” Wilkins says. “There were 26 storms with very little stable weather in between. A hundred and eighty-six avos crossed the road, 87 the result of active avalanche control.”

Numbers don’t make me as nervous as the area we are passing, where a large forest has been levelled. It resembles a battle scene out of World War One.

“Boulders were plucked out of the river bed, hurled across the road and found 200 m up in the bush,” says Wilkins. “Granite boulders are heavy. One the size of your pillow is hard to budge, and an air blast picked them up like confetti.”

Wilkins drops another sobering fact as we pass the no-stopping signs: “Moving traffic is harder to hit. If you were parked here and saw an avo come down you’d have roughly 20 seconds to get out of the way.”

After a tour of other start zones, Wilkins drops me back in Te Anau, with me a lot wiser to the ways of the Darran Mountains snow-pack. He tells me a parting anecdote: “I was out checking the road early one morning—there was snow on it almost to Milford Sound—when I came across kiwi tracks. They went for miles, petering out as the snow thinned.” We decide that the bird must have been in the habit of using the road as a track through the forest to get away from the snow—another example of kiwi ingenuity at work on the Milford road.

On one of my trips up the road I hitch a ride with Chris Hughes, who drives a minivan to Milford Sound and back each day. At 8 A.M. we pull out of Te Anau, “dodging the rush-hour traffic,” as Hughes describes it. There isn’t another car in sight. On board are visitors from England and the United States, and, like most people who visit Milford Sound, they are hoping for a sunny day to view the scenery.

Hughes has some bad news for them. As we leave Te Anau he points out that the mountains are shrouded by cloud and rain is almost inevitable. He counters the party’s disappointment by keeping up an enthusiastic banter about how driving along the road in a storm is one of the most fantastic things you can do. He confides in me why he is confident the passengers will perk up.

“On one trip I had a van full of elderly folk with really long faces. It was raining. Couldn’t see a thing. When we got to Marian corner, one of them yelled, ‘Look at that!’ Everyone on the other side of the van rushed across, josding for a view of the waterfalls. Then someone spotted a massive fall on the other side. Back they went. I had trouble controlling the van as it lurched up the road. Age was stripped off them and they were kids on summer holiday!”

As we pass through Knobs Flat, in the Eglinton valley, the first drops splatter against the windscreen. Knobs Flat, Hughes explains, is a place where a retreating glacier left its calling card in the form of small hillocks covered in grass. “The knobs out to our left are called kames, and consist of gravel washed into the hollows of a large area of stagnant glacier. When the ice melted 10,000 years ago, this rubble was dumped and left behind.”

Forty minutes later he announces: “We’re now passing over into the West Coast. This pass, the Divide, is the lowest pass in the Southern Alps, at an altitude of 450 m. The Hollyford valley to our right runs out to the sea. The forest is now a mixture of beech and rimu trees with a jungle-like understorey of ferns and vines, and those light orange trees without leaves are a giant fuchsia—glad they’re not one of my pot plants.”

The windscreen wipers slap across on high speed as we sweep down into the Hollyford valley. At Marian corner we climb again towards the subalpine. This is where the waterfalls become too numerous to count, and on one wall it’s as if an ocean is pouring off the edge of a flat earth. We stop at Falls Creek, and Lyttles Fall is as noisy as crashing surf. By this stage, any disappointment among the passengers at not having a sunny day has evaporated, and everyone hurries off the van into rain bouncing to knee height off the road.

Back in the van it is a fight for the towels to keep the windows clear of condensation. Nobody wants to miss the “water-ups,” as Hughes calls them. A water-up is when the wind accelerates down the narrow canyons and hurls a waterfall back into the sky, vaporising it.

We continue up the Hollyford with classical music playing, matching the mood of the day perfectly, and enter the tunnel. Halfway through, Hughes stops and asks us if it’s all right with us to turn the lights off. “I ask this,” he explains, “because once someone hit me over the head with an umbrella and demanded I turn them back on.”

Darkness invades us, and for a split second I think of bashing Hughes myself, but then I enjoy the rest from light. With the lights back on we continue down on a gradient of 1 in 10 towards the daylight.

The tunnel is a bare-bones structure 7.3 m in diameter and 1256 m long, with ribs of rock sticking out where it has been blasted. It is intimidating in its nakedness. A fellow passenger who is used to European tunnels is surprised it isn’t lined and lit, but adds that it would be a shame if it ever was. Water has found its way down through cracks in the mountain and pours down underneath protective corrugated-iron arches, making the tunnel feel as wild as the valley we have just driven up.

We emerge at the head of the Cleddau valley, and the road swings like a snake down the glacial-cut U-shaped valley. We are swallowed by towering mountain walls. Before we get to Milford Sound we will have dropped 792 m in 20 km through subalpine scrub consisting of southern rata, koromiko, mountain lacebark, wineberry, kiokio, silver beech and mountain holly with spiky leaves.

A compulsory stop is the Chasm, and we slosh along the graded track. Despite being soaked, nobody stays in the van. Stout bridges straddle the gorge where the river has carved a groove through fine-grained diorite. We pass an information board explaining how the Chasm was formed. “Harder crystalline stones, trapped in cracks and fissures, are swirled around creating moulins or potholes.”

At the bottom of the sign are some apt words by Henry David Thoreau: “The finest workers in stone are not copper or steel tools, but the gentle touches of air and water working at their leisure with a liberal allowance of time.” Time is something that seems almost to stop among the ancient rimu and beech trees; even though the water is rushing below me it doesn’t seem to be in a hurry.

[chapter break]

For the return trip, I hitch a ride with Works Infrastructure surfaceman Fred Culling and his sidekick Joel Waitiri. Culling is a gentle man who used to be an ambulance officer. He’s near retirement, and his cauliflower ears remind me of my grandfather’s.

Up the Cleddau we go in Culling’s truck, stopping at most of the small bridges to sweep away grit, which is spread when the road is icy. Waitiri uses a mechanical sweeper; Culling and I, shovels. There are more than 20 of these bridges on the section from Milford up to the tunnel. In a place where the rainfall averages 7 in a year, every rivulet needs a bridge if the road is to remain passable. The rain has eased to a drizzle, but the rivulets still rage.

Waitiri turns off his motorised broom, and except for the scraping of shovels the only sounds are from nature. Just as we are finishing, a raucous clatter starts up in the trees above us. The racket is exactly the same as the scraping of the shovels. It increases, until in the trees above us appears a kaka. These parrots, closely related to kea, live in the bush. It is the first time I’ve seen one, and I’m excited by this revelation on the road. To have called it out using a road worker’s shovel seems to me perfect—a metaphor for the relationship between the road, the wildness and the workers. If Works Infrastructure didn’t constantly care for the road, nature would claim it back. Whole sections would cease to exist after a flood; seedlings would grow in the cracks, and avalanches would cover it in debris. Even now as we drive along, moss is growing in the asphalt where tyres fail to pound; resilient strips of green, biding their time.

Culling isn’t a naturalist in the accepted sense of the word, but having worked for 16 years on the road he has learned to notice things.

“Saw a weka down here for the first time the other day. I made sure it went down the bank off the road. Got to look after them,” he says. He has also seen a pair of blue duck in the head of the Hollyford.

Waitiri adds, “We call Fred ‘Tuatara.’ You know, a tuatara’s eyes move independently. Fred’s got one eye on the road and the other on the birds.” We all laugh at the double meaning, and Culling wiggles each eye by way of demonstration.

In the Eglinton, where the flats lap at the feet of the mountains, we have smoko. If the Milford Track, which is several kilometres to the west of us, takes in some of the most beautiful scenery in the world, then driving along the road, which is similar to going tramping in your car, gives access to the most beautiful valley in the world. This place is so friendly you could shelter under a red beech and forget to leave. As we sit there in the sun the driver of a passing coach flicks a newspaper to Culling.

“Notice he gave the paper to me, not to young Joel here. Age before beauty,” he says. “They give us a paper every day as a way of saying thanks for helping them out with the odd tow.”

Culling points out the birds of the Eglinton. There are mohua, or yellowheads, flitting high up in the canopy, their call musical like a canary, with colourful parakeets following. Bellbirds chime away and a pigeon’s whooshing wingbeat is heard. There are tui, fantail, tomtit and brown creeper as well. Kaka live in the valley, but we don’t see any. The Eglinton is rich in birdlife thanks to the efforts of the Department of Conservation, which has traplines set up the length of the road, keeping the rats and stoats under control. If it weren’t for the road, this work would be expensive and difficult to maintain.

A few months later, I return along the road, bound for the mountains. At Marian corner I stop at one of my other favourite places on the road, a small car park close to the Hollyford River. I slither down the short track and squat on a river-worn granite boulder. The river here is a noisy series of boiling cauldrons, with small geyser-like eruptions and swirling green eddies. Ten metres off the road, I can’t hear or see the traffic. I’m next to the road but immersed in Fiordland. Just the way I like it.