The dating game

A life in radiocarbon.

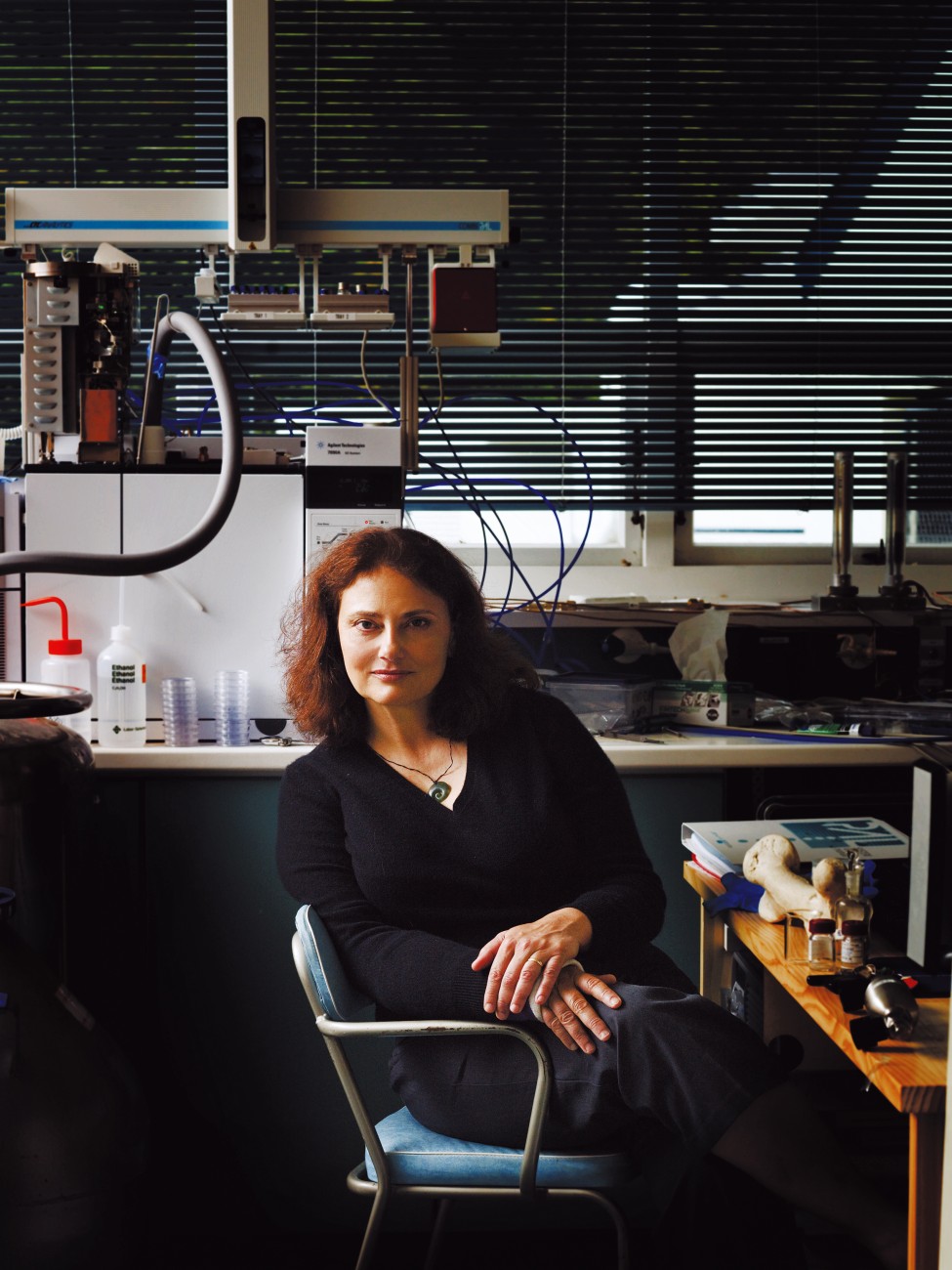

Nancy Beavan Athfield is fresh from a stint deep in the jungle of Cambodia’s Cardamom Mountains, where she has been working to unravel the secrets of ancient human remains discovered on a number of cliff-side ledges. The enigmatic remains, found in large ceramic jars and hollowed-out logs, have increasingly lured Athfield from her day job at GNS Science’s Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory in Lower Hutt and into the world of field archaeology.

She first learned of the discoveries in 2003 when National Geographic Channel asked her to carbon-date bone samples for the documentary Riddles of the Dead. The film-makers were investigating the idea that these jar burials marked the final resting place of people associated with the last royal household of Angkor, which once ruled much of Southeast Asia.

It was an intriguing prospect. For 600 years, the seat of Khmer power lay at Angkor, several hundred kilometres north of Khnorng Sroal. At its height in the 13th century, Angkor was home to a population 30 times the size of Parisat the time, but in 1431 it was over-run by invading Thais and was abandoned. Stories were told of members of the royal family fleeing to seek refuge in the Cardamom Mountains.

Athfield dated the Khnorng Sroal samples to as late as 1620 AD, seemingly dashing the possibility of Angkorian royalty. However, over the years, other sites have emerged to deepen the mystery, including Khnorng Perng and, more recently, Phnom Pel in the far south.

Pondering the origins of an unknown people in the malarial jungle of Southeast Asia is quite a departure from Shakespearean scholarship—Athfield’s first ambition—but then her career trajectory has always seemed guided by fate.

Born in the United States, Athfield abruptly ended her school education in her sophomore year, at 16, when she ran away from home. Much later, she took courses at a small community college in New York. Then someone suggested that she sit an entrance exam for Columbia University. She did, and to her surprise she was accepted.

At Columbia, she gravitated towards physical geography, and while an undergraduate landed a job at the university’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. There she met Wally Broecker, a geology professor who became a mentor. Called the “grandfather of climate science”, Broecker at the time was developing a radical new theory—that ocean currents acted as massive conveyor belts to transport heat around the planet. He was also pioneering radiocarbon and isotope dating, both essential tools for mapping climate fluctuations in the Earth’s distant past.

“From him I learned to think like a scientist,” says Athfield. “He believed that as a scientist, the best place to be was where everything you know is shaken by a new piece of information.”

When Athfield’s then husband was offered a post at GNS Science, she accompanied him to New Zealand and took a job as lab manager in the Rafter Laboratory. Soon after her arrival, she became involved in a raging controversy over radiocarbon dating which seemed to suggest that the Polynesian rat, the kiore, and therefore humans, had arrived as early as 100 AD.

“I realised that it was a good time to get a PhD,” she says. “I wanted to look at how you ascertain the reliability of radiocarbon dates. It was the perfect subject.”

Having ruled out faulty lab procedures, Athfield identified anomalies caused by diet—her doctorate was based on five years’ worth of papers exploring that very issue.

She then began embracing broader issues in archaeology, and contributed to a 10-year project with English Heritage, fine-tuning Anglo-Saxon chronology. But it was the call from National Geographic Channel in 2003 that ignited her passion for fieldwork. “I was excited by these jar burials and driven to find out the answers,” she says.

Keen to continue their research in Cambodia after the camera crews left, Athfield and her colleagues were hampered by that universal bugbear, a lack of funding. In 2009, after years of “crying in the wilderness”, she made a breakthrough when the Australasian Research Council funded her and a team based at the University of Sydney to return to the Cardamoms as part of a larger project to create a Cambodia-wide isotope database.

“We are starting from scratch because the country doesn’t even have extensive geological maps,” says Athfield of the isotope project. And, in an echo of her old mentor: “We must always be open to new ideas and new insights on the past.” To date, the project has brought together geologists, physical anthropologists, ceramic specialists, ethnographers and even a dendroclimatologist (who determines past climates from trees).

With Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture having learned of freshly discovered jar burial sites, she has already scheduled a return trip in July. “I will spend the rest of my life working in the Cardamom Mountains,” she says.