On a wing and a prayer

Maori kites were not only for children, but also a means of communication—between distant hapu, even between humanity and the heavens.

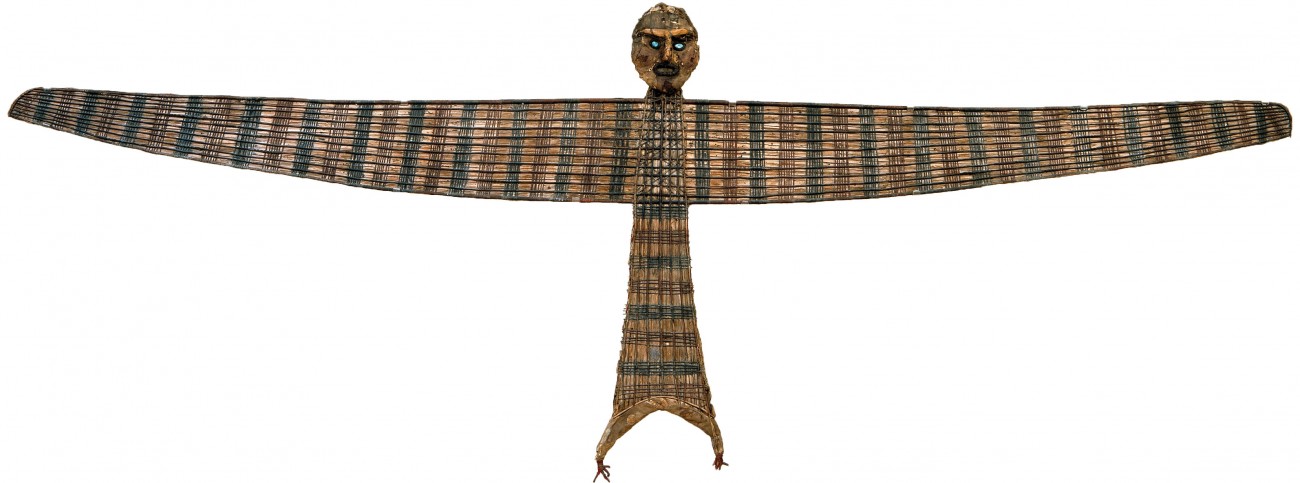

There were 17 named types of Maori kite, in shapes from ovals to fish, small diamond-shaped kites, and bird-like designs with great out-stretched wings measuring more than three metres in span. However, only seven known examples remain, representing just three designs.

Traditionally, Maori kites were made from light-strong timber framing, such as manuka, with lengths of split supplejack for components requiring flexibility. The frame was covered with aute, bark from the paper mulberry, until the tree became virtually extinct and raupo or cutty grass was substituted. Control lines were prepared from flax—scraped, dried, rolled and twisted or finely plaited.

The largest of all surviving Maori kites have a ‘birdman’ form, and only two examples are known, one in the British Museum and the other—with a wingspan of just over 3.5 m—gifted to Auckland Museum in 1886 by Sir George Grey, a former governor of New Zealand who went on to become the country’s premier.

The slender framework of this kite rarely exceeds 10 mm in diameter and is bound together with diagonal lashings of flax fibre. Raupo is bound to the back of the manuka frame, but the wings are not rigid, rather constructed to move gently when the kite was flown, perhaps mimicking the movement of a bird in flight. It features a head, covered with paper (including some strips from an 1884 Government Gazette) and beaten bark cloth. An 1890 photograph of the kite also shows teeth, a moko and hair made from hawk feathers, which have long since disappeared.

Kites were flown, as today, as a form of recreation and celebration to mark important seasonal events, such as Matariki. But they were also used for communication—signals that could be seen from a great distance to communicate between pa—and divination.

Like birds, they were called manu. And, like birds, they were seen as a link between the earth and the sky, between the physical world and, spiritual realm beyond.

The largest kites, manu whara, were the exclusive domain of tribal elders and tohunga, and used for divination.

Often they included an important accessory, a karere, or messenger, which was a ring of lightweight material, such as feathers, sent up the kite string by the wind as a message or appeal to the gods. As it went, incantations, or karakia, were made to assist its ascent and divine the response of the deities as the kite rose and swooped.

The birdman kite was gifted to Auckland Museum to “preserve the practice of making the kites”. Despite being made of fragile and perishable material, the artefact has largely outlived the kite culture that created it, and survived to be instrumental in the rejuvenation of that culture—a potent image of both the craft of Maori kite-makers and the necessity of institutions which preside over these taonga.