New Zealanders in the Spanish civil war

While officially we were neutral in this bitter curtain-raiser for WWII, a handful of volunteers became involved, most of them on the side of the left-wing government fighting Franco and his fascist supporters.

“My journey from Paris to Spain via the Pyrenees was made in company with a group of French anti-fascists…which exceeded 100. ”

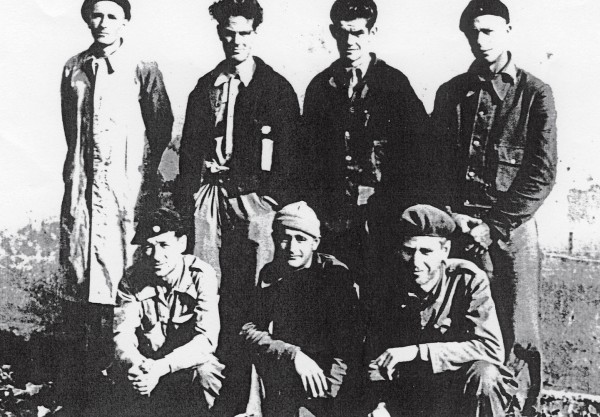

In this company, exchanging war stories with toughened veterans of the Foreign Legion, New Zealander Charlie Riley made the dangerous night climb on foot along mountain tracks into Republican Spain. He was among the almost 60,000 volunteers from more than 55 countries who made this journey, and one of the tiny handful who represented New Zealand. These were the fighters of the International Brigades, who arrived from around the world to support Spain’s democratically elected government following a 1936 military uprising proud to term itself fascist. Seventy years on, the International Brigades volunteers are widely honoured both within Spain and in many of their countries of origin. Yet in New Zealand they are nearly forgotten and, with the exception of an obscure public park in west Auckland, have no memorial. This, then, is the story of the New Zealanders who took part in the Spanish Civil War.

[Chapter Break]

Riley working as a miner in Australia’s Northern Territory when news reached him that the political turmoil that had engulfed Spain some years earlier had erupted into open warfare. He was already a convinced anti-fascist and political agitator, as well as a combat veteran who had reached the rank of sergeant-major in World War I.

Born a Cockney in London’s Tower Hamlets, Riley had migrated to New Zealand as a young man, joined the Royal Dragoons and been posted to France in 1915. His war service had ended when he’d been wounded severely and invalided home. During the Depression he had been active in the Christchurch Unemployed Workers’ Movement and, in 1932, imprisoned for six months for possessing “seditious literature”. After his release he had moved to Australia, where he’d become a skilled miner and an expert in explosives.

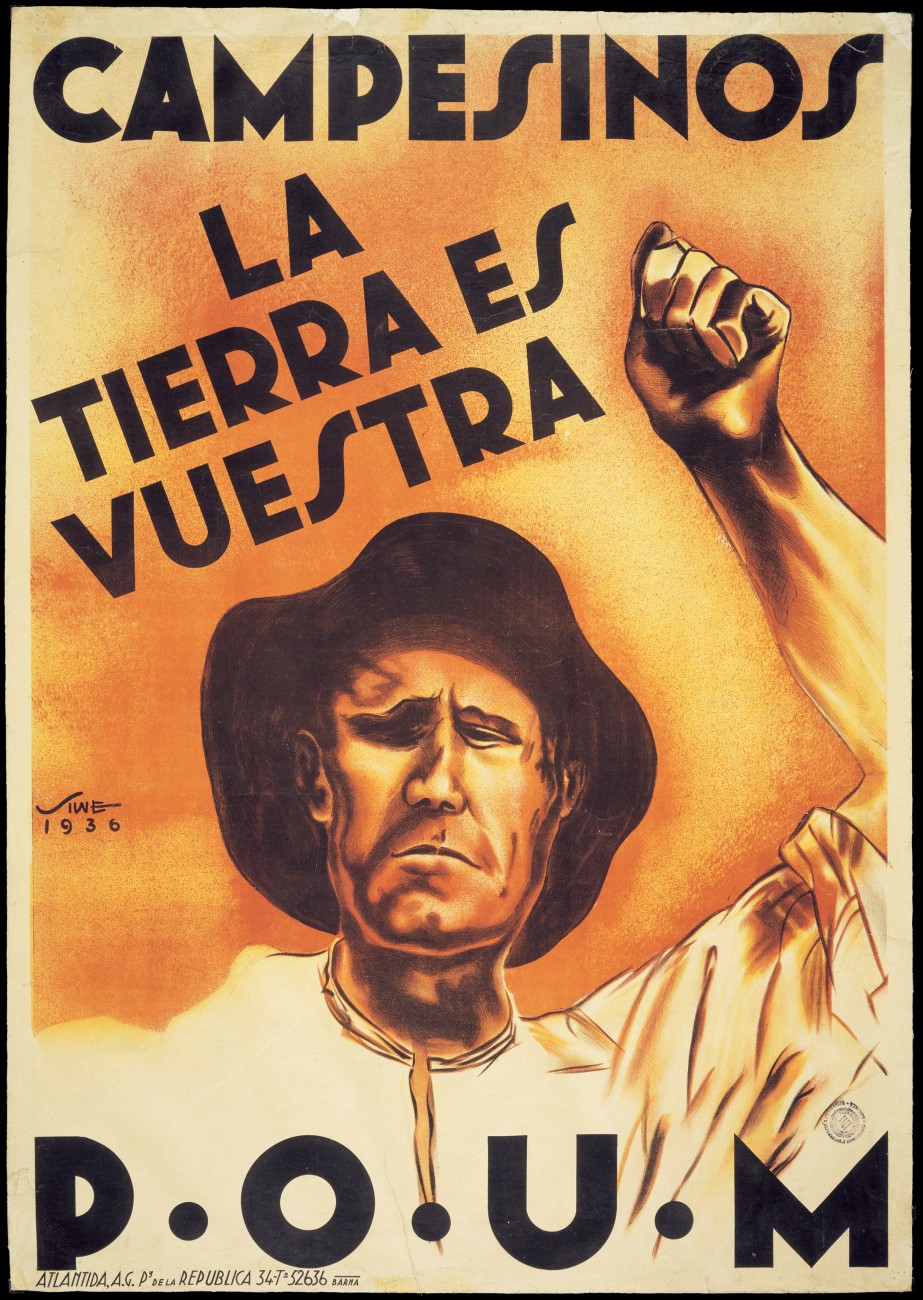

In July 1936, Spain’s centre-left Popular Front government, which had hopes of transforming a semi-feudal monarchy into a modern democratic state, faced a coup by a group of army officers. The coup leader, General Emilio Mola, almost immediately moved aside to make way for the considerably younger General Francisco Franco. The military revolt spread through much of the country’s rural heartland and smaller cities, but failed in the industrial zones and major centres. The navy and most of the air force stayed loyal to the government.

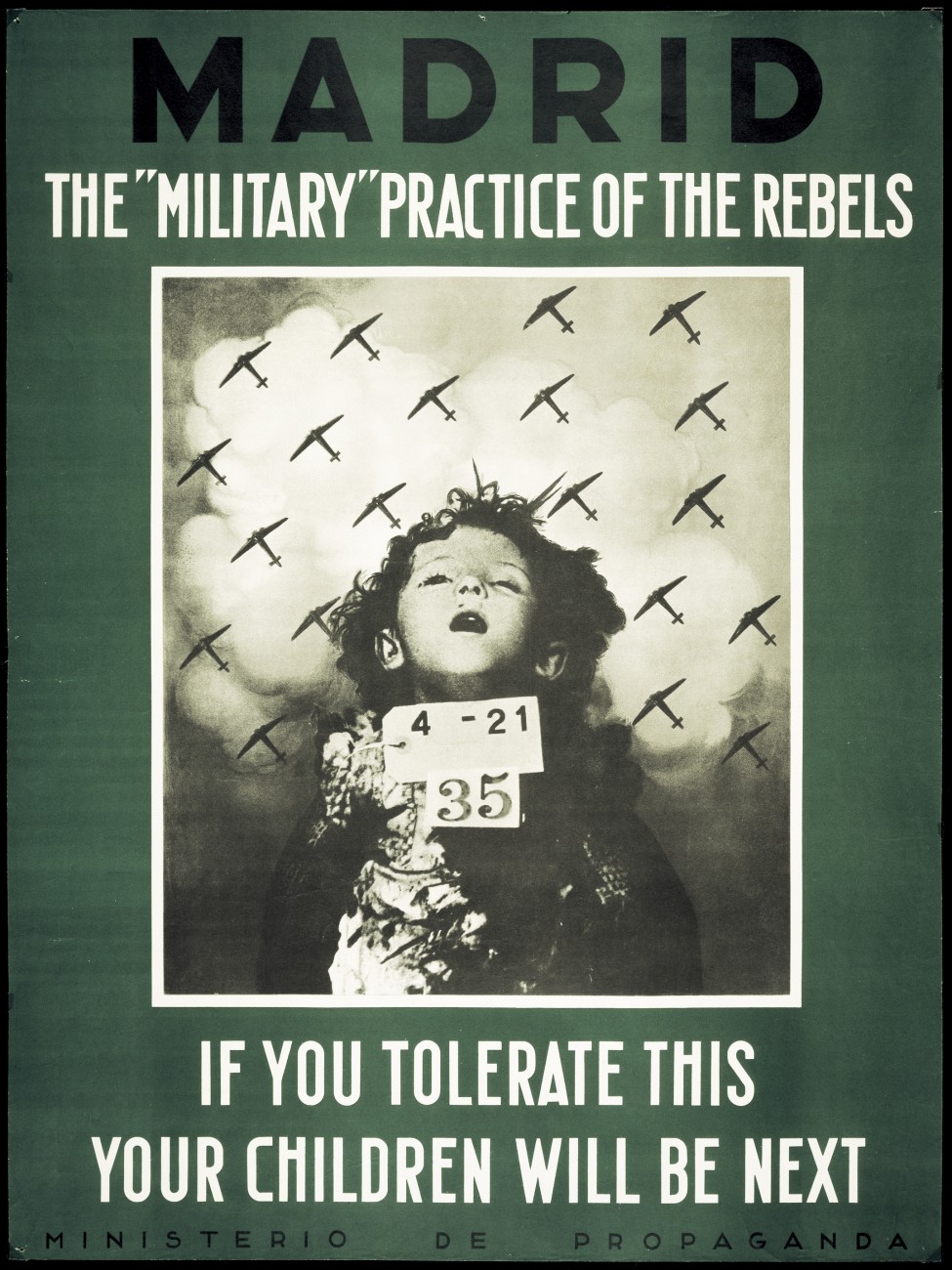

The conflict soon became a stalemate, and to break it, Franco called for support from Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. Both countries responded with contingents of shock troops and their latest military aircraft and artillery, enabling Franco to advance towards the capital, Madrid, with overwhelming superiority in both troops and weaponry. The governments of Britain and France, citing their adherence to principles of non-intervention, declined to support the Republican government, which, in desperation, appealed for military and humanitarian aid worldwide.

From the other side of the globe, Riley came to fight his second war.

“In the early fighting stages,” he subsequently recalled, “there was less than one rifle between each six defenders and many of the weapons were generations old.”

This situation had somewhat improved by the time he arrived and joined the British Battalion of the International Brigades, where his military experience and mining skills made him a valued bombing instructor. In fighting which was frequently hand-to-hand, he proved a disdisciplined and courageous soldier until, during the 1938 Battle of the Ebro River, he received a burst of machine-gun fire.

“After being wounded in the head, face and left jugular artery, both shoulders and arms, I must have presented a pretty sight. One side of my face was a mass of congealed blood, the khaki beret which I had held to my neck to try and stem the flow of blood that squirted from the jugular artery, being saturated with the thick bloody mass… I still remember walking up a hillside to contact the dressing station which lay on the other side.”

Thanks in part to a blood transfusion from his Spanish nurse, Riley survived his second wartime injury and recovered in a hospital in the Catalonian town of Valls before being invalided back to Australia.

“Sometime after I had left Valls, the hospital was bombed by insurgent air squadrons. Nevertheless it had remained untouched almost until the very end (of the war), for the reason that Franco had a country estate there.”

By early 1939, the rock-hard ex-miner was back in New Zealand and campaigning for aid for the refugees of the civil war. As soon as New Zealand declared war on Germany in 1939, he volunteered for the first echelon of what was soon to be known as 2 NZ Expeditionary Force, and, although aged nearer 50 than 40 and twice wounded, somehow made it through the medical inspection. In the Middle East he was wounded for the third time, and once again survived to be repatriated. As the narrator says in John Mulgan’s Man Alone, “there are some men you just can’t kill”. Charlie Riley ended his days in Naenae, a suburb of Lower Hutt, in the 1970s.

[Chapter Break]

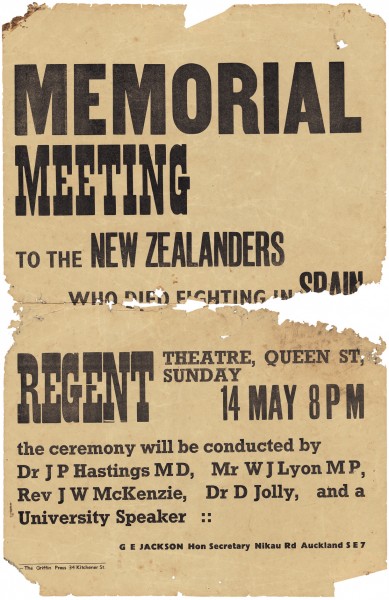

Other New Zealanders who fought in Spain were less fortunate: about half didn’t return. For the International Brigaders in general, mortality rates were appallingly high, and among those killed in the early months of the war were two New Zealanders. Steve Yates, also a World War I veteran, had been dismissed by the British Army for “insubordination” and was working as an electrician in London when he decided instead to join the anti-fascist struggle in Spain. By contrast, Griffith “Mac” Maclaurin was a brilliant young Cambridge mathematician from a distinguished Auckland family of academics who had been converted to left-wing politics after witnessing the rise of Nazism in Germany.

Maclaurin and Yates were with the first group of International Brigades which arrived in Madrid to strengthen the resistance to Franco’s rapidly advancing forces, and they marched up the city’s main avenue, the Gran Via, to the frontlines in the newly built University City. In the face of strafing by Italian planes, fire from German machine-gunners and deadly sniping from Moorish marksmen, they held a position inside the School of Philosophy and Letters. Along with British, French and Polish volunteers, they built barricades along the window sills from the largest books in the departmental library, finding that bullets generally penetrated to about page 350.

Less than two days after their arrival, according to another Cambridge graduate (who later became a professor of classics at Yale), “One gun team was sent ahead to an advanced position but was overrun during the night by the Moorish troops, as we learned from the one man who returned.” Two of the three who didn’t return were Maclaurin and Yates.

Alex McLure, the son of wealthy Canadian parents, was studying at Otago University when the war broke out. He berated his fellow students for their indifference to the threat to Spanish democracy and cajoled them into helping him establish a local aid organisation to raise funds for medical and humanitarian relief. The passionately partisan McLure, however, was not content to work from the sidelines. In early 1937 he returned home to Canada, and in March that year sailed to Spain with a large group of volunteers. He was posted to a unit of the mainly Canadian McKenzie-Papineau Battalion and was killed in its first action, at Fuentes de Ebro, on the Aragon front.

McLure’s former classmates from Otago, who included the writer and Rhodes scholar Dan Davin, were deeply affected by his death. According to Keith Ovenden’s biography of Dan Davin, A Fighting Withdrawal, a short story written several years later contained a rueful indirect reference to the two mens’ lives, with a McLure-like character named McGregor killed in Spain. “Spain was a place you got killed in, for something. Oxford you just went on dying in, for nothing.”

Very little is known of another New Zealander, the young Wellingtonian William Madigan. Apparently a striking figure with a keen sense of adventure, he had spent time travelling as a hobo in the United States before arriving in Spain in early 1938. He was killed some months later, probably during the Battle of the Ebro.

Others to die included Jack Kent of Hawera who was drowned off the coast of Valencia in May 1937 along with 500 other volunteers when their ship, the troop carrier Ciudad de Barcelona, was torpedoed by an Italian submarine.

Fred “Robbie” Robertson, a roving left-wing seaman and hero of the Napier earthquake, left New Zealand by ship in 1936 and arrived in Spain later that year. He was killed in February 1937 in the horrendously bloody Battle of Jarama.

Robertson’s best mate from Napier, Tom Spiller, was the best-known public face of New Zealand’s International Brigaders. A lanky and athletic type, he laboured on government work schemes during the Depression and left the country in 1936 seeking revolutionary action. In January 1937 he set out for the war from London, and, like Charlie Riley, entered Spain by climbing mountain trails across the Pyrenees at night. In Barcelona, he was joined by Robertson. The two men received their Russian-made rifles just 24 hours before being ordered to the front, and the first bullet Spiller fired was directed at the enemy.

He later went up to the Jarama front as part of a 10-man machine-gun unit. On its first day in action, the unit was hit by a shell and only Spiller and one other man survived. One night, he buried 80 of his fellow International Brigaders in a single grave. In a letter to his parents, he described a night bayonet attack to regain lost positions: “It was in this attack that Robbie (Robertson) was killed.”

Deeply grieved at the loss of his friend, Spiller carried on fighting and took part in the ferocious and disastrous Republican counter-attack at Brunete, west of Madrid. He stopped three bullets, and while recuperating in Spain was asked to return home to recruit more volunteers. This he did, having to overcome personal anguish in the process. In early 1938 he wrote: “At times I get to thinking things over and get terribly depressed over our frightful losses in Spain. At times I get very near crying and it’s only with great difficulty that I prevent myself from doing so.”

Nonetheless, Spiller toured Australia and New Zealand, living out of a small truck and speaking vehemently in favour of aid and military support for Republican Spain. His dedication was unquestionable but he failed to recruit other New Zealanders, and, by the time he tried to return to the war himself, all International Brigaders were being withdrawn. In later life Spiller became a prominent trade unionist and an icon of the Auckland left. He returned to Spain in 1981 to visit the Jarama battlefield and lay a wreath in memory of his friend Fred Robertson.

Another survivor pyschologically scarred by the war was Timaru-born Bert Bryan. He arrived in Spain in early 1938 and came through the horrific Battle of the Ebro before being repatriated. He was severely affected by his experiences under fire, never fully recovered and died of alchoholism in 1961.

The war attracted youthful thrill-seekers along with those acting out of principle. William “Murn” McDonald, the son of a prominent Dunedin doctor, left New Zealand in disgrace after serving a sentence for robbing a bank in Palmerston North. He arrived in Spain while transporting a military aircraft and decided to sign up with the American Battalion of the International Brigades. Apparently a well-liked and dedicated soldier, McDonald survived several major engagements, including the Battle of Jarama, in which he was wounded in the shoulder, the only member of his five-man patrol to survive. In World War II, he joined an elite British unit, possibly the Special Operations Executive, and spent a long period as a prisoner of war.

Perhaps the most colourful figure of all the Kiwi volunteers was Eric Griffiths, the quintessential dashing young aviator. Raised in the Wellington seaside settlement of Eastbourne, he started taking flying lessons in high school and joined a New Zealand air circus while still a teenager. He spent time in China ferrying planes for warlords, and took part in the American expedition to Antarctica led by Admiral Byrd.

When war broke out in Spain, its government desperately needed fighter planes and pilots, and Griffiths signed a lucrative mercenary contract. There is no question, however, that he was firmly on the side of the Republic, with his one good arm.

On his return to New Zealand, Griffiths had a flying suit tailored to accommodate his shattered limb. He soon headed for Hollywood to seek film work with fellow Antipodean Errol Flynn, the Hollywood action hero, whom he had met in Spain. When his attempt at a career as a stunt-flier didn’t work out, he left for China to courier planes for the nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. World War II brought Griffiths back to New Zealand, where he became an airforce test pilot and was later sent to Fiji. There, bearing the rank of flight lieutenant, he died in 1942 while testing a new American plane, the AiroCobra.

Of similarly mixed motivations, the young Masterton man Bernard Gray was working as a chef in London in the early 1930s and saving to marry his fiancée. When he heard of the International Brigades, he joined up with the aim of increasing his earnings. Despite this unlikely background, Gray proved an able fighter and earned the coveted title of tanquista after knocking out an Italian tank (which he named Sylvia, after his beloved). He later drove an ambulance and, although he made no secret of his mercenary status, was evidently popular with his comrades. Gray was yet another International Brigader who later served in World War II, and he lived until 1980.

[Chapter Break]

In all, perhaps a dozen New Zealanders served as combatants in Spain, although there may have been others as yet unidentified. However, a great many more, including some very prominent individuals, supported the Republican war effort by supplying funds and humanitarian assistance. The main body that provided aid to Spain was the Spanish Medical Aid Committee. This nationwide organisation, commonly known as SMAC, grew out of the small Dunedin relief committee of which the secretary and guiding spirit was Alex MacLure.

From these modest beginnings SMAC expanded to become one of the most effective relief organisations New Zealand has seen. It held public meetings, film screenings, raffles and exhibitions, and organised speaking tours of civil war veterans, all aimed at jolting New Zealanders into supporting Republican Spain’s resistance to the menace of fascism. The most generous supporters were the trade unions, whose members sometimes pledged regular deductions from their pay, along with lump sums from their national bodies. In this way SMAC funded the purchase of a field laundry truck and an ambulance for the Republican forces, and in the later stages of the war provided medical supplies for the huge numbers of refugees held in camps across the border in France.

The committee’s highest-profile activity, however, was selecting and funding three New Zealand nurses to travel to Spain to work in field hospitals there. The leader of this trio was René Shadbolt, then aged 33 and head sister of Auckland Hospital’s casualty ward. In the words of her nephew, writer Maurice Shadbolt, she was “tall, angular and acerbic”. Of no pronounced political leanings, she had little respect for authority and held very high principles.

Shadbolt was joined by the younger, fresh-faced Isobel Dodds, a staff nurse at Wellington Hospital who came from an activist Labour family in Auckland. “There is in everyone, hidden or otherwise,” said Dodds, “some spark of idealism… This was perhaps the reason I started nursing, and now, when I may put that knowledge to some real use in a land divided by civil war, which threatens democracy, I am proud that I should be one of those to help in unfortunate Spain.”

The final member of the party was 40-yearold nurse aide Millicent Sharples, who was working in a private hospital in Levin.

The three were given a series of lavish public farewells, but on the day their ship was to leave, in May 1937, they were detained for several hours by Auckland police. Shadbolt, accused of being a card-carrying communist, snorted with derision and declared that she had “never even been the secretary of a tennis club”. The women finally managed to board their ship, and Police Minister Peter Fraser, an old friend of the Dodds family, later admitted that the police had acted on orders from the newly elected Labour government, which had been deeply alarmed at the prospect of “three dedicated revolutionaries flying New Zealand’s flag in Spain”.

Greeted in Barcelona by air-raid sirens and the drone of bombers, the three women were first taken to the central Spanish town of Huete, where they worked with a multinational staff at a makeshift hospital in an old monastery. After some months, Sharples, who held a driver’s licence, was posted to the Aragon front, where she drove an ambulance and was wounded by shrapnel. She then returned to New Zealand, while the other two remained at the Huete hospital, treating an endless stream of casualties with limbs either missing or frostbitten.

The following year Franco’s army broke through the Republican defences, bringing the fighting close to Huete. Truckloads of casualties would arrive straight from the battlefield to be laid on the floor in rows, which doctors and nurses inspected, deciding who should be given the chance of surgery. The two New Zealand nurses worked 48-hour shifts without a break, Shadbolt giving anaesthetic while Dodds struggled to keep the equipment sterile. Eventually, the wounded were operated on with unsterilised instruments. When it was no longer safe to remain at the hospital, it was evacuated at three hours’ notice. The two nurses were devastated at abandoning so many of the wounded. In a group of about 1000 people, including as many International Brigaders as possible, they left in the middle of the night on a three-day train journey to Barcelona, coming under fire from Franco’s troops. Next, Dodds and Shadbolt were transferred to a hospital in the foothills of the Pyrenees. They arrived with only a uniform and a nightgown each, so they wore one while they washed the other. Their final posting was to a very large hospital at Mataró, on the coast north of Barcelona. There they came into contact with the brutal “war within the war”, as anarchists, socialists and “Trotskyists” (revolutionary Republicans accused, bizarrely, of being fascist terrorists in league with Franco) were imprisoned and executed by communists acting on the orders of Stalin.

In September 1938 came the announcement that all International Brigades would be withdrawn from Spain. On their return to New Zealand, the nurses embarked on a nationwide appeal for medical supplies and funds for the victims of the war, especially the thousands of refugees crowded into camps in Perpignan, just over the French border. One who was of particular concern to Shadbolt was a former patient of hers at Mataró, “an elegant, eloquent and wispily bearded” German officer named Willi Remmel. In all her appeals on his behalf to the New Zealand government and other agencies, she made no mention that Remmel had become her husband during the war. Her efforts to gain entry to New Zealand for this dedicated anti-Nazi were unsuccessful, and the outbreak of war with Germany prevented the two ever meeting again.

Starched and formidable to the end, Nurse Shadbolt spent many years as matron of Rawene Hospital, beside Hokianga Harbour. Eventually, and with great reluctance, she accepted an OBE for her services, but she was also the recipient of a less widely heralded form of recognition. On her return from Spain to her home in New Lynn, Auckland, the local council decided to honour their courageous citizen by naming a new park after her. Shadbolt Park stands today at the end of Portage Road in Waitakere City, its political significance long forgotten.

In addition to the three SMAC-funded nurses, other New Zealand nurses worked in Spain in a variety of roles. One, who spoke good Spanish and was described as dedicated and efficient, was a young Christchurch woman named Dorothy Morris. She had trained as a nurse during the Depression and, like Shadbolt, was strongly affected by the plight of the unemployed. When war broke out in Spain she joined the University Ambulance Unit, which set up a children’s hospital on the Costa Brava to care for refugees fleeing from Franco. The following year she was placed in charge of a Quaker-run children’s hospital in Murcia, in southern Spain, where she contributed to saving many sick and starving children. After evacuation to France in 1939, she continued working with the Quakers, running the office that established camps for the Spanish refugees who had poured into France and organising milk supplies, libraries and education for both children and adults. In May 1940, as the German army advanced on Paris, Morris became a refugee herself.

Aucklander Una Wilson worked with an Australian medical unit at a frontline hospital during the siege of Madrid. Some of her accounts of treating up to 600 casualties a day under near-constant aerial bombardment have the quality of nightmare. She and an Australian nurse were often the only theatre sisters available, and they worked day and night. “I used to just flop down on the theatre floor or somewhere if there happened to be a couple of hours to spare,” she recalled later. In 1937 she treated further floods of critically wounded men from the Battles of Jarama, Brunete and Teruel.

A rare bright spot in Wilson’s memories was the 1937 May Day celebrations in Barcelona, which included a ceremony at the city’s cemetery, newly filled with war dead. “We, sprinkling flowers over the graves while at the edge stood the military men at attention with the village folk forming a background giving the ‘Salut’, while the band softly played the ‘International’. It was a touching scene, believe me. When we had finished all our flowers we stood on one side while speeches in every possible language were made… If I hadn’t been there New Zealand would have been left out, and so I’m quite pleased with myself.”

[Chapter Break]

In spite of the dreadful working conditions and the need to improvise, the standard of medical treatment during the civil war was remarkably high. This was probably due to the arrival in Spain of volunteer medical personnel with the freedom to use their initiative to improve existing systems. In his definitive history of the civil war, British historian Sir Hugh Thomas states that, “Medicine generally gained enormously from the new methods of treatment of war casualties introduced into Spain by the Republican Army.” One of the principal medical innovators was Dr Doug Jolly, whose achievements place him among the greatest figures in New Zealand’s medical history.

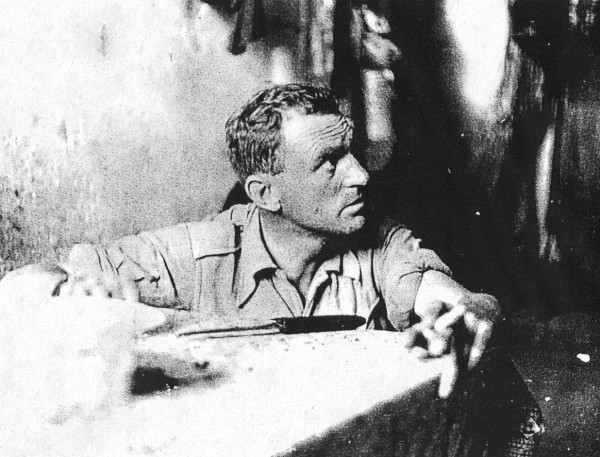

Born in Cromwell, Jolly graduated from Otago Medical School and, in 1932, left for London to gain specialist qualifications as a surgeon. He was due to sit the final exam when he learned that doctors were desperately needed by the Republican Army Medical Service, to replace those who had joined Franco’s forces. A Christian socialist by conviction, the 28-yearold medic dropped his studies and made the journey to Spain. There he was placed in charge of a mobile surgical unit of 14 people who between them spoke half a dozen different languages. The unit was promptly posted to Madrid, which, in late 1936, was the first European city to face mass aerial bombardment. With erratic supplies of only rudimentary medical equipment, Jolly and his team were faced with an endless stream of casualties, both military and civilian, of all ages.

For almost two years Jolly and his overworked team moved from one battlefield to the next, always operating near the front lines. Aurora Fernandez, one of his nurses, recalled “dear Dr Jolly performing a Maori dance from New Zealand. He was never tired. Once in the middle of the night an ambulance came with an urgent case. It was after a fortnight when no one had slept… Dr Jolly got up as if nothing had happened and operated on the man.”

“During my earlier days in Spain,” said Jolly, “we were able to choose the largest vacant house in a village…in which to set up our field hospital… Soon, however, with the increase in aviation and the enemy’s numerical superiority “During my earlier days in Spain,” said Jolly, “we were able to choose the largest vacant house in a village…in which to set up our field hospital… Soon, however, with the increase in aviation and the enemy’s numerical superiority in planes, all villages near the front were unsafe.” His unit tried using camouflaged tents, but soon learned that “enemy night bombers, unable to find their legitimate objectives in the dark behind our lines—crossroads, ammunition dumps, etc.—were in the habit of unloading over any available light. No matter how we tried to camouflage our tents with caked mud, branches, tarpaulins, etc. there was always the glow from our high-powered lights… After receiving a number of unwelcome loads of bombs we were forced to go underground whenever possible.”

Jolly established five different hospitals in unused railway tunnels by boarding up the ends and laying down a floor. “We were safe in the tunnels,” he recalled later. “Once, near Bisbal de Falset, we found a great natural cave which, after a hundred sappers had spent a day levelling the floor, was adequate for the installation of 150 beds and an operating theatre.” Surgical instruments were sterilised in fish kettles on Primus stoves, and the only warmth for the patients was from alcohol burned in open pans, a dangerous practice when ether was used as an anaesthetic.

To deal with the sometimes overwhelming numbers of casualties, Jolly developed his own “three-point forward system” of triage.

A front line clearing post sorted casualties into those with critical injuries and—far more numerous—those less badly hurt. Emergency transport—as rapid as possible but sometimes only mule carts—carried the most serious cases to a field hospital, often in a cave, tunnel or wine cellar. The effectiveness of this system, Jolly maintained, depended as much on the courage and speed of the transport crews as on the doctor’s surgical skill.

In late 1938, Jolly, along with all other foreign nationals, was repatriated from Spain. By then he had been made a lieutenant-surgeon (the equivalent of a major) and awarded the Ebro Medal for his work during the Battle of the Ebro. His repatriation report stated: “He has always wanted to operate as close as possible to the firing line. His relations with the comrades are magnificent. Although not affiliated to any organization, he is an excellent anti-fascist.”

Back in New Zealand, Jolly took only a brief break before undertaking a nationwide speaking tour. Together with fellow veterans of the war Bert Ryan and Charlie Riley, he travelled throughout New Zealand to bring attention to the desperate situation of Republican refugees following Franco’s victory. He also found the time to draw on his experiences in Spain to write a textbook that described in detail his three-point forward triage system. Field Surgery in Total War was published in the United Kingdom in late 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain. The Lancet urged that it “be read at once by every young surgeon who may be called upon to treat war casualties”. The British Medical Journal later described it as “compulsory reading for all young aspiring war surgeons on both sides of the Atlantic”. Adapted for use by the US Army during World War II, the three-point forward system was said to have “undoubtedly contributed more to saving the lives of patients with abdominal wounds than any other single factor”. Jolly’s book continued to influence the principles of wartime trauma care for 50 years after its first publication.

The author, however, was not content with providing information for others to implement. Like Riley and many other International Brigaders, he signed up at the outbreak of the next anti-fascist war, joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was posted to the Middle East. For the next three years he served with the same dedication he had shown in Spain, winning promotion to lieutenant-colonel and a military OBE. The award citation refers to “Lt Col. Jolly’s untiring zeal”, while a later testimony says he “showed a willingness and capacity to do most exacting work beyond what seemed to be the limits of endurance for long periods of time”.

This extraordinary medical pioneer and lifelong humanitarian was certainly one of the most notable war surgeons of the 20th century. The internationally respected British medic Dr Archibald Cochrane worked with Jolly in Spain and described him as “a man of the highest competence, for whom I developed a great admiration. He was…in my opinion, the most important volunteer to come from the British Commonwealth.” Like all the other civil war participants named here, with the sole exception of René Shadbolt, Jolly doesn’t rate a mention in the proudly inclusive New Zealand Dictionary of Biography

[Chapter Break]

Only New Zealander is known to have joined Franco’s army in the civil war, and he did so enthusiastically. Philip Cross, the son of a doctor from Island Bay, Wellington, was an improbable character—an actor, film-maker and apprentice bullfighter who left New Zealand in 1928 to seek his fortune. By 1936 he was shooting a film in the small Spanish village of Alcala de los Gazules, in a region that supported the Francoists.

“Most of the able-bodied men in the village joined the Royalist army and the five men in the (film) company joined up with Franco as well,” Cross subsequently related. He fought in the siege of Madrid, was captured at the town of Boadilla and, along with a pair of Castilian aristocrats, was sentenced to death by firing squad. He and his co-condemned escaped this fate after Franco’s troops retook the town. Cross was later wounded and invalided out of the war.

In a New Zealand newspaper article Cross recounted an atrocity story that reads like and may well have been—the plot of a B-grade movie of the period. One of the actresses in his film, said Cross, was a young Spanish woman, Pastora, the daughter of a noble Castilian family and sister to his friend Jacinto, one of the two who had faced execution with him in Boadilla. Cross stated that after recovering from his wound in England, he had returned to Barcelona to make a film about the work of an “entirely neutral” relief fund for women and children. There, very improbably, he had found Pastora again. To prevent her father from supporting Franco, the Republicans had taken her hostage and forced her to work as a frivola, or naked dancer, and “singer of lewd songs” in a Barcelona nightclub filled with “ruffians of every European nationality”. Later, while returning to England, Cross had been informed that Pastora’s father had been killed in Madrid, and that Pastora, on learning that she no longer needed to act as hostage for his life, had killed herself.

There is no evidence to support this lurid tale, which conforms to the pattern of atrocity stories circulated by Franco’s supporters throughout the war. It is possible that Cross wanted to counter the prevailing public mood of admiration for the International Brigaders and to justify his own decision to fight on the other side. His motives do not seem to have been coloured by religious conviction, although the Catholic Church in New Zealand gave prominent support to Franco during the war.

In several local Catholic publications, the war in Spain was interpreted simply as an attack upon the church by communists and anarchists, while claims of atrocities by the Nationalist rebels were invariably discounted. The national Catholic paper Zealandia in fact pursued the line, promoted by Franco’s press chief, Luis Bolin, that the Basque town of Gernika had not been bombed by the German Condor Legion, but rather had been blown up by retreating Red saboteurs.

In 1939, the editor of Zealandia, Father (later Cardinal) Peter McKeefry, met Franco in Spain at a mass to dedicate a monument to General Mola, killed in an air crash less than a year after he’d proclaimed the generals’ revolt. The paper reported that Franco shook McKeefry’s hand and told him “he had been deeply touched by the sympathy and help of his fellow Catholics in all parts of the world”.

[Chapter Break]

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War coincided with the election of New Zealand’s first Labour government, which found the conflict presented it with a dilemma. Although the government had emerged from a defiantly left-wing tradition and still retained ties and obligations to the union movement, which now strongly backed the Republicans, it was cautious about alienating its broad base of supporters, including many who were staunchly Catholic. It was also reluctant to take a position that might align it with New Zealand’s minuscule but influential Communist Party, the guiding force behind SMAC. Accordingly, although it had a Republican sympathiser at the League of Nations in the person of its high commissioner, Bill Jordan, it was content to allow its foreign policy to be determined by Britain, which maintained a non-interventionist stance despite the massive and ominous military interventions of Germany and Italy.

Britain’s insistence on standing by as Spain was used as a testing ground for the military might of the Axis powers was the cause of deep dismay to those with first-hand knowledge of the war, including a young Southlander who witnessed its early stages.

Geoffrey Cox was a Rhodes scholar who preferred to enter journalism rather than the more prestigious professions for which he was eligible. He was a junior reporter on the liberal London daily the News Chronicle when, in late 1936, the paper’s star foreign correspondent was arrested by Franco’s forces on suspicion of spying. The world’s press expected the Republican government to fall before the rebel advance in a matter of weeks, so the News Chronicle picked Cox—young, unmarried and dispensable—to replace its jailed war correspondent and cover what was widely anticipated to be the imminent fall of Madrid. Instead, Cox found himself reporting the city’s successful resistance and the arrival of the first International Brigades, a scene unprecedented in modern times.

When, after six weeks, it became apparent that Madrid would not fall easily to Franco, and that the war would be both prolonged and internationally significant, Cox was recalled to London and replaced by a more experienced journalist. In a feverish few weeks he turned his experiences in Madrid into a book, which was rushed into print by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz. Defence of Madrid, an outstanding work of committed reportage, has recently been reprinted in an expanded edition. Its author is still alive at age 96 and still writing, and delighted to see the reissue, after almost 70 years, of his first book.

It appears at a time when the civil war is again a subject of intense interest both inside and outside Spain. In July 2006, the Spanish parliament passed a “law of historical memory”, aimed at recalling the identities of those killed in the war, including thousands of civilians who lie in unmarked mass graves, and those who suffered afterwards under the long dictatorship of General Franco. Only in the last decade has it become safe to discuss the war openly in Spain, and the new law marks the first move by the state to address the demands of victims’ groups for moral and material compensation.

The law has come into force only now that nearly all adult survivors of the civil war have died. Of those New Zealanders who shared the Republican cause, only Isobel Dodds, today known as Isobel McGuire, remains alive, in Auckland. Many years after her return from the conflict, she said of her decision to go to Spain, “I thought it was the right thing to do at the time and never changed my mind.”