New Zealand gets cable

The nation’s first connection with the world could receive just 10 words a minute

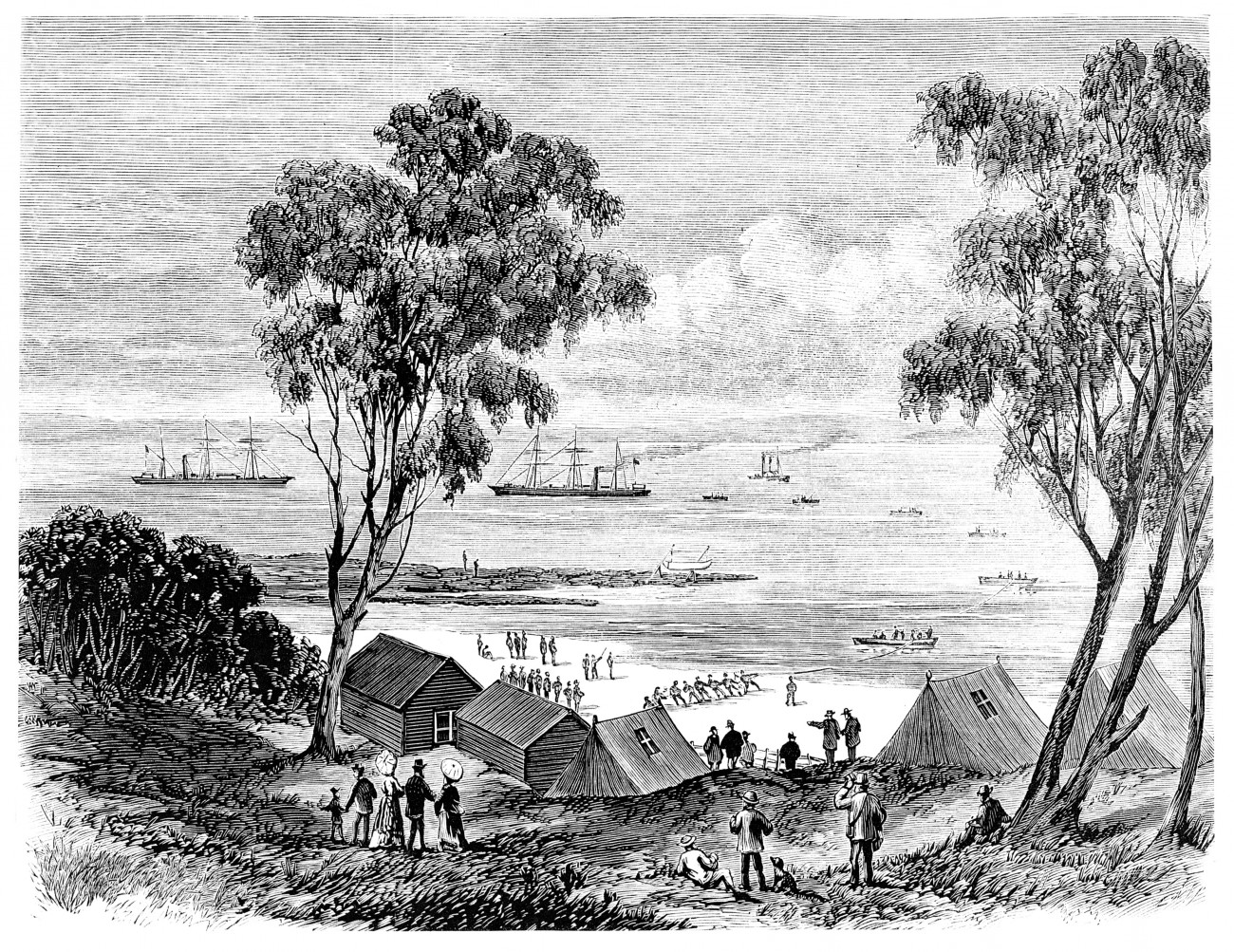

On the afternoon of Thursday, February 17, 1876, Hemi Matenga stood on the shore at Schroder’s Mistake, north of Nelson, watching a ship’s boat in the bay labouring a hawser to shore. At the other end was the cable-layer Edinburgh, and not far off, the larger Hibernia. Matenga, from nearby Wakapuaka pa, waded into the foaming sea until only his head was above water and grasped the thick rope. With the help of a score of men the line was secured, and more ship’s boats then tied up to it at intervals to feed a thick cable from the Edinburgh to a purpose-built cable house.

It was the last link in an ambitious 24,000-kilometre telegraph wire that ran by land and sea from London to India and through Southeast Asia to Australia before taking a last plunge beneath the Tasman to finish up at the farthest outpost of the British Empire.

Now, thanks to this most modern of technologies, the country would for the first time be connected to the world. Instead of existing in a time warp, where ripples from momentous events elsewhere took months to reach its shores, New Zealanders would henceforth exist and act in the same moment (more or less) as people in London or Paris.

At the time, the South Island was more populous than the North, and Nelson, the country’s fifth-largest town, was an obvious choice for the terminus of New Zealand’s first international cable. However, the place name “Schroder’s Mistake” didn’t inspire confidence in the new venture and it was soon changed to the prosaic “Cable Bay”.

Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel had conceived the idea of an international connection in 1870 as part of an economic development policy. The world was then in the grip of cable fever; overland lines criss-crossed Europe, Russia, India and the United States and with increasing daring they were being draped beneath the sea. In 1866, an Atlantic cable had been laid in spectacular fashion by the 19,000-tonne leviathan, Great Eastern.

Faster ships and a Suez isthmus crossing had cut the time taken for mail to reach New Zealand from five months in 1840 to two months by the 1860s. And the Panama Canal cut it even further—to just 48 days. But New Zealand’s new submarine cable eclipsed everything that had gone before, conveying news around half the world in a matter of hours.

The cable was state-of-the-art—a copper core insulated with gutta percha (a latex from Malaya), wrapped in jute and steel wire. But operators at Cable Bay and elsewhere were obliged to sit in a darkened room painstakingly decoding incoming electric signals with the aid of light focused on the twitching mirror of a galvanometer. The best of them could manage merely 10 words a minute.

Now, almost 140 years later, we are again laying cable. As in 1876, light is involved, but this time not to carry mere words, but sound and moving images that cross oceans in a fraction of a second. One thing, though, hasn’t changed: we still do it in the name of economic development.