Mervyn Taylor

The renaissance man of Karori

My mother still has them: a collection of New Zealand School Journals from the 1940s, kept in her “antiquities cupboard” along with an ancient mahjongg set and an obsolete 8 mm movie camera, the recorder of family life. On sick days I used to pore over these journals, and what I remember most about them is the engravings, each one melodramatically captioned with a phrase from the story it accompanied: “Rajah Brooke hears behind him the crackle of flames as he runs”, “Soldiers, sailors and Maoris came rushing into the pa”, “His head was driven through an oil painting of Slugg’s father.” Whether it was these particular engravings that seized my imagination, or those from another favourite childhood source, the five-inch-thick family Bible with its depictions of the molten calf, the brazen serpent, Jonah being heaved into the sea, a love of engravings has stayed with me.

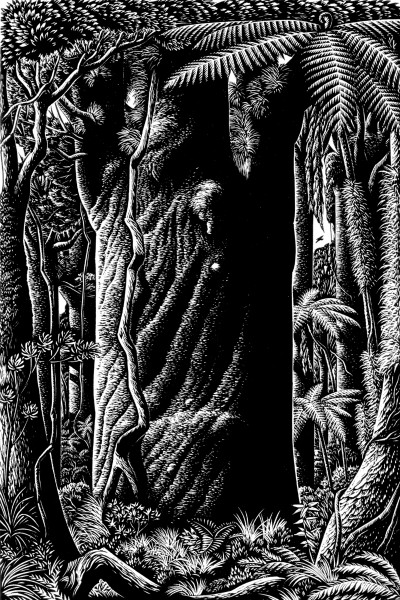

Looking back through the Journals, I see illustrations by Russell Clark, George Woods, E. Mervyn Taylor, and others. But it is Taylor who interests me. I seem to have bumped into him over the years—or into his work, at any rate. I went through a bookplate phase, and Taylor was a great designer of bookplates, those visual haikus that seek to capture the essence of the book’s owner. But it was his engravings of nature that really marked him in my mind as a kindred spirit. Flipping through my copy of his Engravings on Wood, I see his rendering of the kauri tree known as Te Matua Ngahere, “father of the forest,” its massive bulk offset by a delicate tracery of ferns, grasses and epiphytes. Here is his sublime tui, with its grave eye and flamboyant froth of white feathers at the throat. The pair of huia, poignant in extinction, his bill a dagger, hers a scimitar. The sacred kotuku rising through star-studded heavens, framed by lightning bolts and comets, guiding Tane to the source of spiritual wisdom. Each one is a work of inspiration. They move me still.

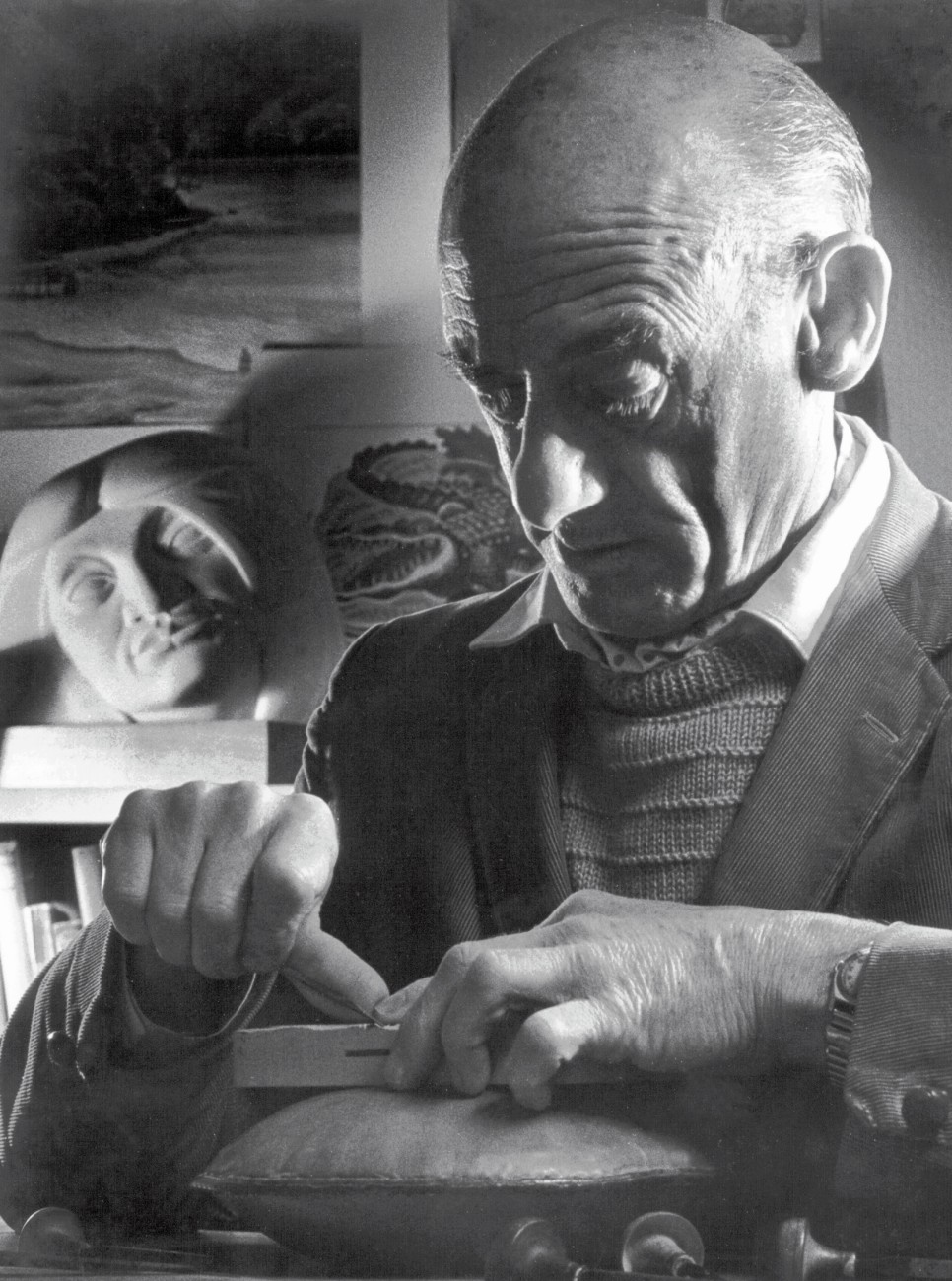

I knew next to nothing about the man. His brief introduction to Engravings on Wood is mostly about technique. I wanted to know about the hand that held the chisel. Now, with the publication of the superb E. Mervyn Taylor, Artist: Craftsman, by Dunedin printmaker and journalist Bryan James, that knowledge gap has been filled.

The story begins in 1906 in the Auckland suburb of Grafton. Taylor did not get off to a good start. A bout of scarlet fever around the age of five left him with a weakened heart, and several years later he contracted polio. Thanks to his mother’s nursing and daily massaging of affected muscles, Taylor recovered, but the disease shortened one leg and left a legacy of painful muscle cramps in his neck and back that persisted throughout his life. The long recuperation from polio meant he was not able to start secondary school until he was 15, and after a year of lacklustre progress in every subject except art, he left.

Remarkably, that single year at Auckland Grammar School sparked in Taylor the desire to become a professional artist—“a laughable prospect in New Zealand at this time,” writes James. Culturally, the country was in a period of stultifying conformity. Britannia ruled not just the waves but the tastes of her subjects. Innovation was discouraged and art careers non-existent.

What could have planted such an ambition in the young Aucklander? He certainly didn’t acquire it from his parents. Although his mother dabbled in watercolour and oil painting, both she and her husband, a postman, disapproved of their son’s artistic aspirations. Solidly middle-class, art for them was no way to get ahead in life. As in many lives, the seeds of eventual greatness would remain hidden. “[Taylor] never recorded what had prompted his passion,” writes James, “nor told anyone who remembers now, but it was a bright flame and it kept burning fiercely until his death.”

Nevertheless, from about this point in his life certain cogs began to be dropped into the mechanism that would later mesh to produce Taylor the artist. The first was his parents’ decision to apprentice their boy for six years to a manufacturing jeweller in the city. Years later, working in the studio of his Karori home, scribing with infinite finesse the hairline cuts of his wood engravings, he would no doubt look back with gratitude on that training; the oneness of hand and eye that marks the true craftsman.

It is indicative of Taylor’s strength of character that despite his serious childhood afflictions he plunged into competitive sports during his apprenticeship years, winning prizes in cycling and rowing and playing for the curiously named Epiphany Hockey Club. He was drawing and painting, too, but no record of this teenage work remains—Taylor burnt it all later in life, calling it “rubbish.”

Taylor finished his apprenticeship just as the Great Depression was beginning. It was not a good time to be in the jewellery engraving business. “Instead of buying jewellery or gold or brass plates, people were trying to sell their valuables,” recalled Taylor. Being “last on” at his firm, he was the first to be laid off as work dwindled. But even in this setback the well disguised hand of fortune was at work. With a friend, Taylor set up shop as a window dresser and ticket writer. This work would give him valuable experience in graphic design, freehand lettering and concept sketching, as well as enhancing his people skills and providing plenty of opportunity to work to deadlines.

And then, in 1935, another door opened. Taylor heard that a Wellington tobacco company had a vacancy for a designer in its advertising and publicity department. He applied for the job, and got it. Tossing his possessions into the back of his Morris 8, he set out for the capital.

Writes James: “Taylor was soon to discover that the act of leaving home and the city of his birth and upbringing released in him psychological energy that had been long repressed. He would spend the last 28 years of his life working at a furious pace, as if to make up for it.”

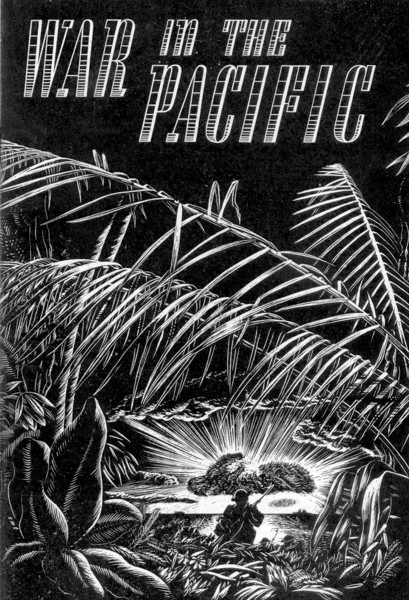

For the next few years Taylor’s life was a whirl of drawing cigarette boxes and advertising posters by day and working on his watercolour and printmaking techniques at night—along with a weekly dash of ballroom dancing and regular socialising with other members of Wellington’s burgeoning art community, among them Russell Clark, George Woods and Eric Lee-Johnson.

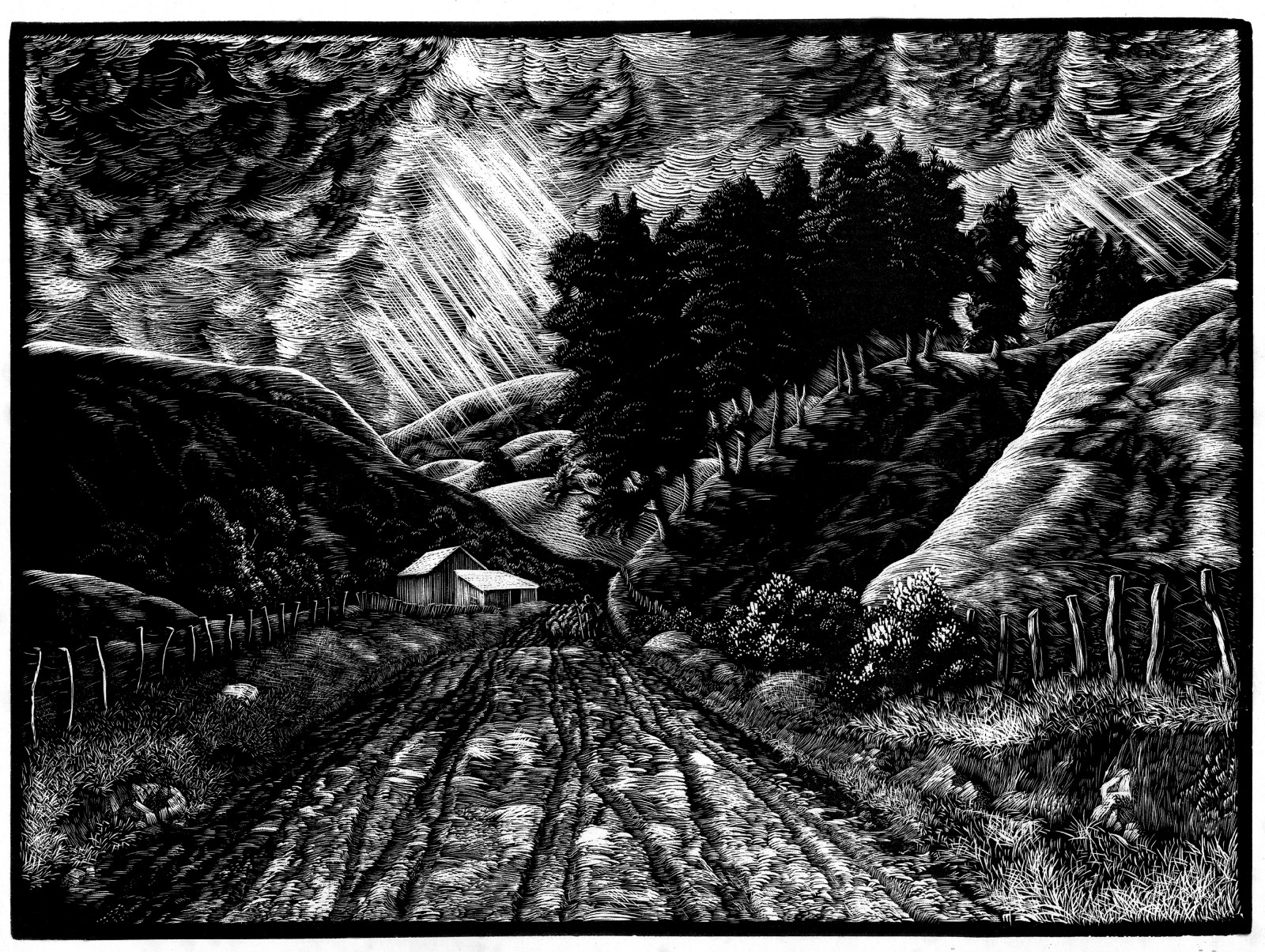

Already, in these formative years of his art, Taylor knew the direction he wished to take. Writes James: “In the back of his mind was the blank place on the map of New Zealand art that he wanted to chart: the natural world; not the distant landscapes that obsessed so many painters, but nature close to hand, nature within reach.”

Above all, he wanted his art to be accessible to the everyday New Zealander. He believed art should be for the common man as well as the cultured elite. Printmaking was a means of taking art to the people. “Taylor felt that woodcuts, linocuts and lithographs could find their way into the homes of people who would not otherwise buy original art of any sort, let alone original art by a living local artist,” writes James.

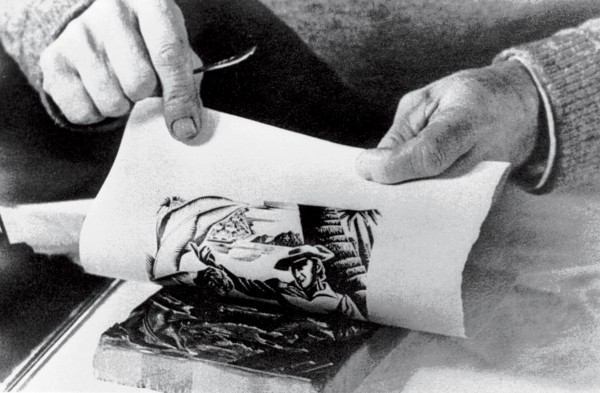

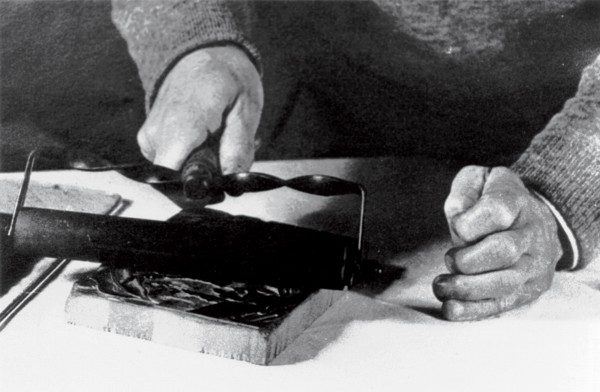

Within the galaxy of printmaking possibilities, Taylor gravitated towards one of the most demanding and least practised styles: wood engraving. While woodcuts can be produced by anyone with a piece of wood and a sharp knife, wood engraving where the work is cut into the end of a block, not its face—requires specialised tools (called gravers) and very hard, close-grained wood that can be polished to a mirror smoothness.

Why did Taylor choose to major in one of the obscure corners of the visual arts—a field in which materials were scarce, tools costly, teachers few, and demand limited? He had the technical savoir-faire, of course—the result of his years in the jewellery trade—but James believes it was visual directness and strong design possibilities of wood engravings that suited what Taylor was trying to achieve.

His first engraving, Dark Valley, depicted a rutted country road with a mob of sheep being driven towards a distant woolshed. Crooked fenceposts lead the eye towards sun-bathed hills, where a row of macrocarpas cast deep shadows. It was a classic New Zealand scene, and, rendered with Taylor’s loving attention to detail, a celebration of the natural world.

But Taylor was not satisfied. Engraving requires supreme self-confidence lines once cut can never be erased or reconsidered. Taylor, a perfectionist, felt he had not sufficiently mastered all the ingredients of perspective, lighting and design required for working in this unforgiving medium. So he put his gravers aside, and for the next eight years concentrated on his broader artistic development.

“When he resumed wood engraving it was with remarkable fecundity,” writes James, “as if he had been practising subconsciously all the time. In a sustained period of just ten years he cut more than 200 blocks, became nationally and internationally recognised, and produced most of the major creations of his artistic life.”

This period of intense productivity coincided with Taylor’s appointment as art editor of the New Zealand School Journal, in 1945. Here was an ideal vehicle for him to express his love of nature, and his engravings of fantail, kaka, weka, mahoe, even the humble garden snail masterfully capture the character of his subjects. The poet Denis Glover, a close friend and business partner of Taylor’s, wrote: “He looked at things we all know and presented them with a brilliance that alone can illuminate the commonplace.”

Yet after only two years at the Journal Taylor felt the familiar restlessness and frustration of walking to the beat of an employer’s drum. He was paid a pittance, beset by administrative demands, and felt his creative life slipping away. There was nothing for it but to take up the freelance life again.

His growing reputation meant steady work, but it was a trickle rather than a flood. As well as continuing to receive commissions from the Journal, he illustrated books of poetry by A. R. D. Fairburn and others, engraved native trees for Forest Service bulletins, and produced dozens of bookplates for bibliophiles. “He made do,” writes James, “but only just.”

The 1940s were testing times for an aspiring freelance artist, and not just financially. In his introduction to the 1946 Arts Yearbook, historian E. H. McCormack wrote: “In spite of some assuring signs, our cultural life is thin and erratic.” The New Zealand art scene remained overshadowed by European tradition. The Yearbook’s editor, Howard Wadman, argued that a truly indigenous artist must draw inspiration from his own history and adopt the resources of his own civilisation—and this is precisely what Taylor was doing. Wrote one art critic, “Unlike much shoddy New Zealand art and writing, his engravings are native in character and not merely by affectation. His Tui is a real tui, not a transplanted nightingale.”

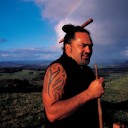

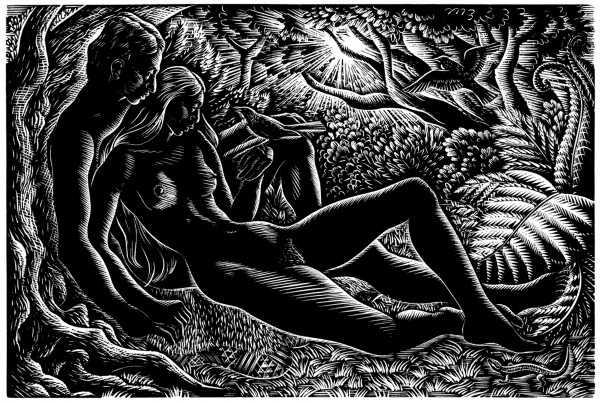

It wasn’t just indigenous flora and fauna that interested Taylor. Increasingly, he felt drawn to Maori mythology. In fact, it was his wife, Edelweiss (everyone called her Teddy), who suggested he explore Maori themes. She had grown up in Wanganui, and heard the legends first-hand from local Maori. Taylor had met Teddy on the ballroom dance floor. They married in 1937, and by the mid-1940s had two children, Terence and Jane.

James notes that without Teddy’s support—not just artistically, but in her willingness to accept the financial vicissitudes of her husband’s career—Taylor could not have become the artist he was. She was his agent, model, publicist and exhibition organiser, and his greatest admirer.

Spurred by the artistic possibilities of Maori tradition, Taylor immersed himself in the subject, reading Sir George Grey’s Polynesian Mythology and making repeated visits to the Dominion Museum to sketch Maori artefacts. Out of this passion for Maori culture came some of his most iconic work: Hinemoa and Tutanekai, Maui taming the sun, Maui stealing fire, and a spectacular engraving called The magical wooden head, in which a tohunga challenges the occult power of a carved totem.

As with nature, Taylor felt it was his role as an artist to make Maori culture accessible to his countrymen. He saw himself as an artist-craftsman or artist-designer, writes James, someone rooted in the community and whose duty was to improve the lot of his fellow man. “He had little time for art that did not have a direct function of purpose, that could not be part of everyday living.”

This belief in the utility of art also showed itself in a deep interest in architecture. Taylor came to regard architecture as “the mother of the arts”, recalled one of his friends, the eminent Wellington architect Maurice Patience. “[He] loved our profession, and one could guarantee that if he were in architectural company discussion would soon turn to the artist’s role in buildings.” Every contract for a major new building, Taylor argued, should include a sum of money allocated to a commissioned work of art to be associated with the building. There was a degree of self-interest here, of course: Taylor hoped he would be one of the commissionees.

Taylor and his architect friends didn’t just talk about the importance of art in everyday life, they established an incorporated society and gallery, the Architectural Centre, to give public expression to their ideas. Its chief activity was the publication of a bimonthly magazine called Design Review, which explored the essence of good design in modern life. Taylor was its art editor and publisher, and ran the magazine for five years. It folded soon after his departure to pursue his greatest dream.

For some time Taylor had had in mind the idea of illustrating all the major legends of Polynesia—from New Zealand to Easter Island to Hawaii, the three apices of the “Polynesian triangle.” There was no way he could tackle such an immense project without jettisoning his freelance illustration work, and no publisher was willing to fund him. So he applied for the only scholarship available to New Zealand artists for full-time study, a five-hundred-pound annual bursary offered by the Association of New Zealand Art Societies. In his application, Taylor stated that he would start with the New Zealand legends, and to amass the necessary background knowledge he would live in a Maori community for a period “to make studies and drawings of types.” Attached to the application was his engraving of the magical Maori head as a taste of what could be expected.

The selection panel was unanimous: Taylor could have the scholarship for two years. With Teddy minding the fort in Wellington, Taylor set out for Te Kaha, a strongly Maori community on the East Coast. Living in the Te Kaha hotel, sketching taonga in the local marae and setting up his easel for landscape work, he became a familiar figure in the isolated community. His presence at the local school, where he talked to the pupils about his work, and sketched several of them, would have an unexpected but significant repercussion: two of the pupils went on to become important New Zealand artists: Cliff Whiting and Para Matchitt.

But it was to be a short-lived idyll. The dream foundered on finance and ill-health. The muscular pain left by his childhood bout of polio was becoming an increasingly debilitating presence, and he found that supporting his family in Wellington while living in paid accommodation in Te Kaha was impossible on the scholarship money alone. Then there was the pressure from regular clients to accept special commissions, such as those relating to the 1953 visit of Queen Elizabeth. Taylor could ill afford to offend these clients, as he would have to rely on them for future work. With reluctance, he informed the association that he could not complete his project.

Though domestic difficulties were pressing upon him, internationally his star was rising. The American Museum of Natural History showed an exhibition of 50 prints. Taylor, the first New Zealand artist to have a solo exhibition in New York, could not afford the fare to attend. In any case, he considered it a “half-and-half” recognition of his gifts. As James notes, “The museum’s reason for showing his work was not because it was ‘art’ but because the prints depicted very accurately New Zealand’s natural history.”

His bread and butter still came from commissions for wood engravings or its quicker, less refined, cousin, scraper-board illustrations. A Forest Service calendar, a logo for the Historic Places Trust (still in use), a health stamp, a steady call for bookplates. He was also called upon to redesign the Official Crest. For 45 years the two figures on each side of the crest—a flag-bearing woman and a taiaha-wielding Maori chief—had faced outward. Taylor had them face each other, immortalising his wife in the process by using her as the model for the female figure.

But Taylor realised he could no longer expect to make a living exclusively from engraving. The New Zealand market was too small to focus on one technique, and a fringe one at that. And the physical and mental demands weren’t getting any lighter. As Taylor pointed out to an interviewer, “You have to think out every move before you touch a block. Once a cut is made, there’s no undoing it. I once tried repairing a mistake with ‘plastic wood’ (an artificial filler), but it was no use at all. It’s hard on the eyes, and it’s hard on the neck. I won’t touch this work in the evening, either. The shadows from the lights make it deceptive, and I can’t gauge the depth of the lines properly. When you’ve put several days’ work into a block, you daren’t risk making a mistake.”

And there was the persistent problem of materials. In today’s environment of commerce at the click of a mouse, it is hard to appreciate just how frustrating it would have been for Taylor to obtain the materials he needed. Foreign currency restrictions were such that he could not buy boxwood or rice paper himself, and art supplies dealers would not import such specialised items. Once, in a stroke of good fortune, a returning soldier brought him a large piece of top-quality Turkish boxwood. Taylor eked it out for many years, using it only for his finest work. He commented, “Sometimes, when I have designed an engraving, I get out a piece of boxwood, but after I have almost caressed it like a miser, I put it back and use beech. Oh for a forest of boxwood in my back yard!”

As a result, Taylor began to produce watercolours, murals and, in a marked departure from the two-dimensional, sculptures. Again, serendipity was involved in the decision to sculpt. Taylor was in Christchurch to check the page proofs of a book of his engravings. While visiting the studio of his artist friend Russell Clark, the latter handed him a small piece of Mt Somers limestone, cleared a bit of bench space and suggested he “have a go.” The work, Hina, completed a couple of years later, is a Maori woman’s face tilted on an angle. On seeing it, Clark told Taylor he was “a natural”. The experience, writes James, “sparked a passion for carving in the round that was to give Taylor some of his greatest personal satisfaction, and open a new pathway in his career.”

Still more surprises were in store. In 1958, the artist who described himself as a “real homebody” was invited to visit the USSR, US and Britain. For the host nations, the invitations were as political in purpose as they were cultural. Writes James: “The USSR was particularly anxious to show the West that it was not a nation of backward serfs, but a technologically advanced, modern state… Similarly, the United States felt it vital to show the Eastern bloc the successes it was having with capitalism and democracy. With each government fighting the Cold War on the cultural front, giving all-expenses-paid visits to artists and businessmen was a regular feature.”

It was the chargé d’affaires of the Soviet Embassy who set the ball in motion, approaching Teddy Taylor at a gallery opening in Wellington to ask if her husband would be willing to visit the USSR and provide a touring exhibition of his work. (That exhibition would turn out be the largest in Taylor’s lifetime, comprising over a hundred works.) When, at another cultural function, Teddy mentioned the Soviet invitation to an American diplomat, a matching offer to spend four weeks in the US was promptly made. Later, when Taylor reached London on his return from the USSR, yet another invitation awaited him: an offer of two weeks in the UK courtesy of the British Council. (Clearly, if you’re an artist, it pays to have your wife attend cocktail parties!)

Taylor’s letters home during his trip away reveal the downside of such junkets: a break-neck schedule. In the USSR, force-fed on interminable cathedral and museum visits, not to mention operas, ballets and plays, he wrote “I don’t think there is anything so tiring as going on day after day acquiring culture… As for double-breasted marble women, I’ve seen enough to last a lifetime.”

The trip’s impact on Taylor was considerable. To his delight, he found that Europeans and Americans tended to place artists on a pedestal—a far cry from the tall-poppyitis of New Zealand. This recognition made him even more certain of his calling as an artist-craftsman. “I have been able to see myself in a better perspective,” he told Teddy as he prepared to return home.

The trip gave him the confidence to put aside his engraving tools and turn to less physically demanding methods of making art. With failing eyesight and worsening arthritis, there was little chance he could have continued to produce the intricate engravings of the previous decade, but it was still a courageous step for a man whose income depended exclusively on his artistic success, an artist-craftsman. “I have been able to see myself in a better perspective,” he told Teddy as he prepared to return home.

Wood sculptures satisfied his growing love of the three-dimensional, and the mystical process of stripping away the surface to reveal the inner form, while murals offered the chance to work on a grand scale. Of this impulse, his friend John Beaglehole, the famous Cook historian, wrote: “No doubt every man with creation in him wants to do something big…to be known for a large gesture against the sky.”

By the early 1960s, murals were Taylor’s major form of work, produced in ceramic tiles, carved in wood or painted. James notes of Taylor’s work in this period that a distinguishing feature was his incorporation of Maori elements. “It was something he consciously set out to do, because he saw Maori as an essential part of the natural order of life in New Zealand, who could no more be excluded from his art than could the bush, the landscape, or the individual creatures he featured.” Few other non-Maori artists of the time cared to feature Maori culture so prominently in their work.

One of his most ambitious projects was a wooden mural for Wellington’s Broadcasting House, depicting the signs of the zodiac. Carved from a single slab of kauri measuring almost two metres by one metre, the panel took him 700 hours to complete.

The commissions were coming thick and fast, and in 1964 he was invited to submit designs for decimal currency, due to be introduced in 1967. He felt, notes James, “at the peak of his creativity.” In June, just prior to beginning workon the new notes and coins, he began to feel unwell, and complained of chest pains. After a restless night, Teddy took him to hospital the next morning. He died that day of heart failure, aged 57.

His death was front-page news. Wellington’s Evening Post called Taylor’s passing “a grievous blow to this country’s artistic community” and a “loss to the New Zealand public whose interests Mr Taylor so effectively served during his life.” Bill Ngata, private secretary to the Minister of Maori Affairs, said his people had lost a champion.

A retrospective exhibition at the National Art Gallery in 1967 included 570 works. The Dominion said it was the largest retrospective of a single artist’s work ever held in New Zealand. Of Taylor’s artistic journey, the newspaper wrote: “At 57 many an artist has said all he has to say and is drying up or repeating himself. But not Mervyn Taylor. At 57 he was finding new paths to explore.”

Shortly after Taylor’s death, Teddy came across a note he had written and pinned inside a cupboard in his studio. “As an artist I aspire to become a craftsman, and as a craftsman I aspire to become an artist.” The thought echoes the words of the great engraver and typographer Eric Gill, in whose company Taylor would not have needed to feel humbled. “Art is skill; that is the first meaning of the word.”

First and last, skill was what Taylor was all about. A modest man, a family man, he pursued his artistic calling resolutely, even when more comfortable avenues of making a living were available. Like the craft in which he excelled, he cared not about the surface of things but rather the substance beneath.

“He was more than a mere artist, two a penny when people want to ‘express their nothingness’ today,” wrote Denis Glover, “he was a craftsman-artist. The Renaissance would have understood him exactly.” His biographer, a printmaker in his own right, has understood him well, too. James has crafted an informed, sympathetic account of an artist who is less well-appreciated than he should be. Perhaps in time, like the kotuku rising, the full sweep of his contribution to New Zealand art will be realised. And not just to art, but to a couple of generations of New Zealanders who learned of their world through his eloquent images.