Laughter in the night

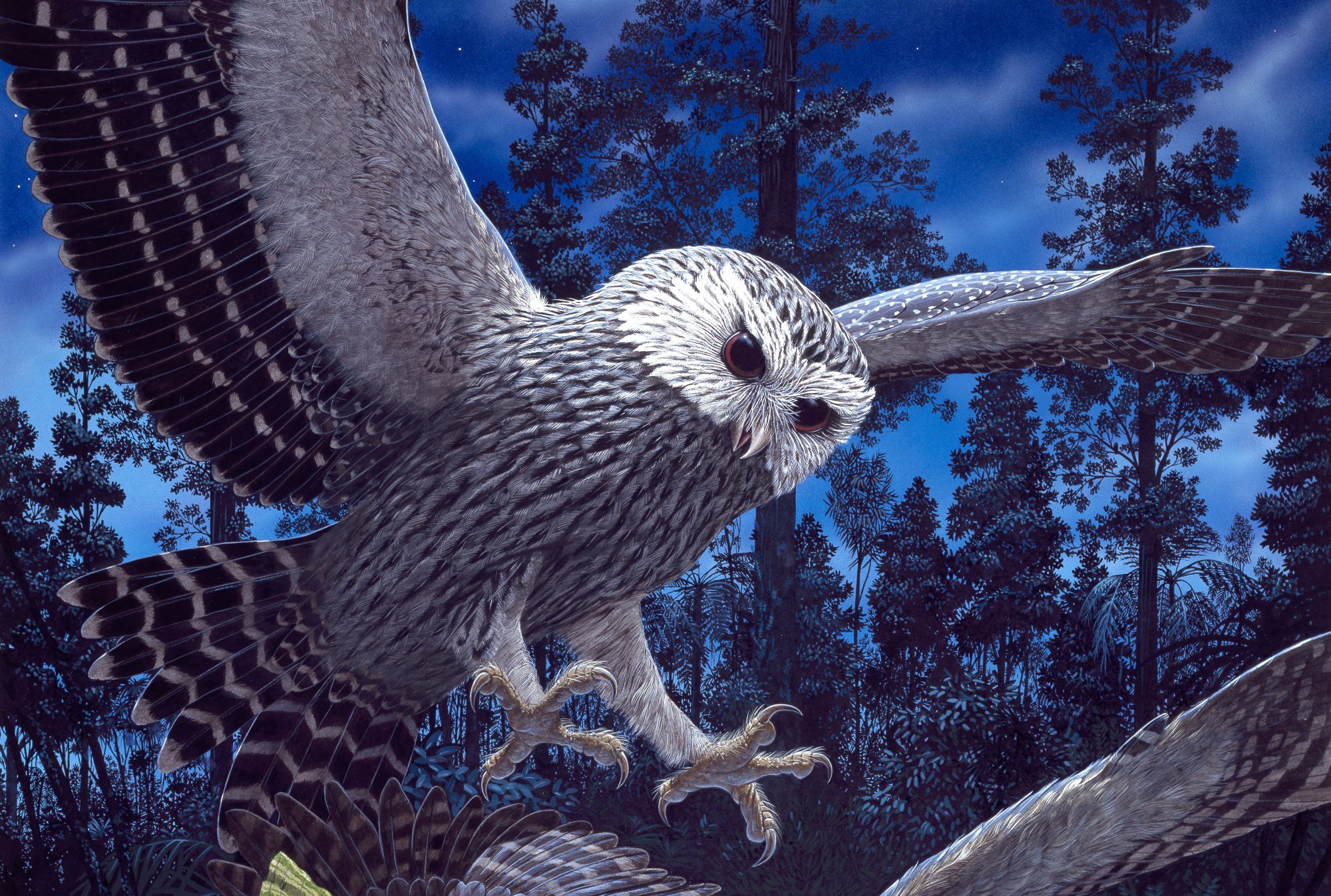

In days of old, the night forests of New Zealand echoed to the screeching “laugh” of an owl twice the size of a morepork, which preyed on any creature smaller than itself. Although the laughing owl has not been positively sighted for 80 years, its relics are yielding insights into our fauna as it was ten millennia or more ago.

Before humans brought their retinue of mammalian predators to these shores, New Zealand’s birds fled only from birds. By day, Haast’s eagle (with a wingspan of three metres and talons the size of a tiger’s claws) and a huge harrier—both now extinct—preyed on the larger species, while the New Zealand falcon harassed the small.

By night, the forest was the domain not just of the morepork, but also of a much larger predator which hunted in silence and struck down prey ranging in size from beetles to birds as large as itself. Few creatures were safe from the fearsome whekau, the laughing owl.

When not hunting, this owl laid claim to its forest territory with a series of chilling cries, likened by some who heard them to maniacal laughter. Other calls, possibly to keep the members of a pair in touch in the dark bush, were like men “cooeeying to each other,” wrote W. W. Smith, one of the few Europeans to describe the laughing owl’s habits.

Laughing owls did not long survive the European assault on the land. In the preceding thousand or more years of Polynesian occupation, kiore, the small Pacific rat, had consumed much of the birds’ traditional fare, but the rats themselves had become a major food item for owls.

Then new animals arrived, and the owl changed its diet again, hunting mice and goldfinches. Later again, ferrets and stoats—liberated to stem the tide of rabbits—and cats began their deadly work. Predators that could kill females and young at the nest, they proved lethal.

Now little remains to remind us that the laughing owl existed at all. Twenty-two mounted birds and 28 skins reside in museums and private collections, two whole birds are preserved in alcohol, and 17 eggs lie in cotton wool in museum drawers. There are a few photographs, some stories and the fading memories of the remaining few people who saw or heard the living bird.

The laughing owl, Sceloglaux albifacies, was about 40 cm from beak to tail, weighed 600 grams and had a wingspan of about 70 cm—similar in size to the Australasian harrier. The owl inhabited all three main islands and probably Great and Little Barrier as well, but not the Chathams.

The first owl to be preserved was collected at Waikouaiti on the North Otago coast in 1843 by Percy Earl. He sent it to the British Museum, and it was described the following year.

Seventy years later, the last one was found dead on the road near Blue Cliffs Station in South Canterbury. Since then, despite many rumours and searches, no sighting of a living laughing owl has been confirmed.

Most of the sightings and preserved specimens have come from the South Island. Some were collected on Stewart Island, but only two from the North Island, where reports of the bird were rare, though widespread from Taranaki and the Ureweras south.

The surveyor Morgan Carkeek is said to have found one in an old whare at Porirua Harbour. “On entering an abandoned Maori but in the daytime he found one roosting there. It was very tame, and remained there for several days. He brought it food from time to time, and it made no attempt to escape from the hut. To the Maori of his survey party it was quite a new bird.”

In the North Island, the bird was known as the hakoke or korohengi rather than whekau, as it was in the South, but by the 1880s it was so rare that most people had not even heard its call.

One of the two preserved North Island specimens was shot in the Wairarapa in the summer of 1867/68; it went to the Colonial Museum in Wellington (now the Museum of New Zealand), but is now lost. The other was collected on Mt Taranaki in 1856 by a taxidermist, Martin, who collected for a Captain King. Martin was familiar with moreporks, and commented on the dark brown eyes of this owl (as distinct from the morepork’s bright yellow eyes). The bird went into King’s private collection, which has vanished.

The prominent New Zealand ornithologist Walter Buller belatedly described the Wairarapa specimen as the type of a new species, claiming that its reddish or rufous face separated it from the southern birds, with their whiter mask. However, as there are rufous-faced specimens from the South Island, and such colour variation is common in owls, the North Island specimens are now considered to have belonged to the same species as the southern birds.

Buller did not fare well with this owl. After naming it, he tried to sell the specimen to Lord Walter Rothschild in England, who declined to buy it as it had a morepork’s tail! It seems that its own tail had been damaged, and, there being no substitute laughing owl tail about, the taxidermist had installed one from a close Australian relative of the morepork. Buller was embarrassed at not having noticed such major damage.

The two men who have contributed most to our knowledge of living laughing owls are Thomas Henry Potts and William W. Smith. Potts wrote about the bird from personal knowledge gained during trips into the headwaters of the Canterbury rivers during the 1860s and ’70s.

He saw living and dead owls, but could not understand why Gray (the scientist at the British Museum) had named it a/bificies—white-faced—as none of the owls he had seen had a white face. Nor did he understand why the settlers had called the bird the “laughing jackass.”

He himself had “never been able to trace the slightest approach to mirthful sound in the unearthly yells of this once mysterious night bird.” Instead, he thought the calls sounded like the call of the Cook’s petrel, but that the petrel “lacks the intensity of the dreadfully doleful shrieks to which the owl gives utterance.”

Although he published some short notes himself, most of Smith’s knowledge has come down to us from letters he wrote to Buller. The letters were read to meetings of the Wellington Philosophical Society and published as extracts both in scientific papers and in the large books on New Zealand birds for which Buller was famous.

Smith was a gardener on the large estate of Albury Park in South Canterbury, and laughing owls lived in crevices in the limestone cliffs that are a feature of the area. On his days off, Smith tried to catch the birds. At first he tried using long wires to hook birds out of the crannies, but with little success. Then he collected “a quantity of dried tussock grass and burned it in the crevices, filling them with smoke. After trying a few places, I found the hiding place of one, and, after starting the grass, I soon heard him sniffing. I withdrew the burning grass, and when the smoke had partly cleared away, he walked quietly out, and I secured him.”

In 1881, Smith obtained five birds in this way. One was sitting on an egg that contained a well-grown chick. Some birds and the chick were sent to Buller, but Smith kept the others in captivity and made worthwhile observations. He recorded that laughing owls moulted during the summer, from December to February, and became almost naked. Two of the captive birds were, in fact, stung to death by a swarm of bees in January when they lacked feathers. Full feather loss during moult is extremely unusual in birds. It may be that the captive owls were suffering from some infection such as feather lice, or a dietary deficiency.

Near Nelson, Richard Kingsley also found laughing owls easy to catch. In 1891, one was “squatting on the ground by the roadside near Tadmor.” The finder captured it, tied it by a short length of rope to a pole, and continued on his way. Two days later the bird “had snapped, or in some way got disengaged from the flax string, and was perched on top of the pole.” It “permitted itself to be recaptured without the slightest resistance.” Jacobs, a Nelson taxidermist, bought it for a few shillings. It can still be seen in the Nelson Museum.

In the late years of the 19th century, it was obvious that the laughing owl was becoming very rare. Buller lamented to the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1893 that in the previous three years he had been able to procure only a single live pair. “This owl is now on the verge of extinction,” he concluded.

The live pair was sent off to Rothschild anyway, but not before Henry Wright, a Wellington businessman and early conservationist, had photographed one of them (see page 111). When taken from its cage for the photographs, the owl “manifested so persistent a desire to get away from the light, and to hide itself in the shade of the ferns among which I had placed it, that it was very difficult to obtain a momentary shot in focus, although in the end the result was a highly satisfactory one.” For many years, the Wright photographs were thought to be the only ones ever taken of a living laughing owl.

The decline of the owls was dramatic, but extinction was not inevitable. Laughing owls were easy to keep in captivity. Smith kept his alive for months. A bird caught near Cass in the Canterbury high country lived at the Acclimatisation Gardens in Christchurch for 18 years until 1887. It laid several eggs, but never had a mate, so the eggs and its skin in the Canterbury Museum are the only legacy of its lonely imprisonment.

The live pairs shipped to Britain and Europe also survived well, or at least long enough to be painted and exhibited. G. D. Rowley, author of one of the sumptuous bird books—Ornithological Miscellany—for which Victorian England was famous, exhibited several live owls at a meeting of the Zoological Society of London in 1874. The fate of these birds is unknown, but two were painted by the bird illustrator John Gerrard Keulemans for Rowley’s book. (Rowley noted: “More gentle animals could not be; they allow themselves to be handled without any resentment.”)

The last birds that Buller sent overseas survived a succession of owners. Smith captured them at Albury and kept them for some time, then Buller himself had them in his aviary in Wellington, before shipping them to England where they ended their days in the care of E Dogget in Caius Street, Cambridge. Their skins are now preserved in the American Museum of Natural History.

Zoos had some luck, too. Even after the long voyage, two owls from Stewart Island lived in Amsterdam zoo from 1882 to 1886. One of them is now in the Museum of New Zealand.

Buller sold several thousand New Zealand birds, many of them rare, to overseas collectors and museums, among them at least a dozen laughing owls. Had a concerted effort been made, the species could have survived in captivity even after it succumbed in the wild. The moves afoot in the 1890s to remove kiwi, kakapo and huia to offshore islands did not include laughing owls. Perhaps the laughing owl, as a predator, was not considered worthy of such attention. Indeed, gamekeepers in England at this time were still slaughtering birds of prey as enemies of grouse and pheasant.

No owls were sent to Little Barrier or to Resolution Island, or anywhere else except to the seat of Empire. Although they were still common enough for Sir Francis Boileau to be able to buy a live one in Christchurch in 1895, they were going fast.

W.W. Smith lamented in 1903 that “our old and genial friend is now almost extinct in Canterbury. My last visit to Albury, on the Tengawai River, resulted in a long and unsuccessful search for specimens. Although I found its castings, which were probably one or two years ejected, I could not find any fresh signs of the bird. The district is now closely settled, and sheep roam in large flocks among the limestone rocks the birds formerly inhabited. The residents of the district informed me that they rarely hear the laughter-like call of this once-common owl.”

Smith attributed the disappearance to the introduction of the “weasel by the Government for the suppression of the rabbit nuisance,” but it is likely that the stoat and ferret were far more dangerous to the owls.

After the turn of the century, there were very few reports of laughing owls. In 1914, the bird was picked up off the road at Blue Cliffs that has gone down in history as the last of the laughing owls.

However, some of the most important laughing owl records date from the years just before 1914. South Canterbury, and the Raincliff area in particular, had always been an owl stronghold in European times. At that time, the Parr family lived in a house at the entrance to a small side valley of the Opihi River. The side valley was guarded by limestone cliffs, and blocks of limestone from the cliffs lay on the valley floor.

About 200 metres up the valley from the house was the “owl rock.” Here, in 1909 or soon after, brothers Cuthbert and Oliver Parr photographed a fledgling taken from the nest. Ted Parr, Oliver’s son, showed us the place in 1995. He had last been there about 1940, when his father, anxious that he see the owls, took him to the old nest site. Sadly for Ted, they found nesting material but no owls, though they may have persisted at the site until the 1920s.

To this day, the inscriptions on the rock—”OWL ROCK” and “OLIVER”—bear mute testimony to the owls’ former presence, and to two men who knew the birds as boys.

[Chapter Break]

The Rapid Decline of the owls during the period of European settlement meant that little was recorded of their diet and behaviour in the wild. Some have speculated that because the bird had large feet and legs, and was often seen on the ground, it was a poor flier. However, we know from the fact that Smith noted birds flying over his aviary at night and from the anatomy of the bird that they were good fliers. Avian predators that take big prey need large, powerful legs—and laughing owls took on most things. Which is not to say that they turned up their beaks at humble fare. Smith reported that owls visited marshy ground to collect the large native earthworms found there, and this habit was also reported by the Pans from Raincliff. They said that the owls swooped down from the cliffs and walked around among the sedges in a swampy paddock.

Ironically, most of what we know about the owl and its habits has come from studies of its food remains and roost holes, rather than from the living birds. When a bird of prey eats something, the material is taken into the crop and gizzard and flooded with acidic digestive juices. Later, the indigestible remains are cast back up as pellets, which contain pieces of insect chitin, bones, fur and feathers.

The pellets are cast at or near the roost, one or two a day. As they accumulate below the roost site, or on the floor of a fissure, they dry out and begin to disintegrate. Some roost sites appear to have been in use over tens, hundreds and even thousands of years, and the pellets have formed rich fossil deposits up to half a metre thick.

The first person to notice such sites was W. W. Smith. Then, in the 1990s, we discovered deposits on the West Coast and near Takaka. Since then, laughing owl prey deposits have become one of the most important sources of information for reconstructing the small vertebrate faunas that once existed in New Zealand.

But how do we know that the prey remains were accumulated by laughing owls and not by some other predator? Three lines of evidence point to the owls: the nature of the site itself, the marks of digestion left on the bones and the prey species represented.

Historical reports, especially those of Smith, make it clear that laughing owls preferred deep, dry fissures in cliffs for their roosts. Other records refer to nests under large boulders. The site at Owl Rock is one such. Here we know that owls nested, and the prey remains excavated from the sediments in the hole beneath the rock are typical of those found in cliff fissures elsewhere. Falcons, by contrast, use open pockets on cliff faces rather than fissures, and harriers roost in swamps and tall vegetation.

The digestion patterns are important clues as to which bird was responsible for the bone deposits. The stomach acids of a hawk or falcon are strong enough to completely dissolve most of the bones. Owl acid is weaker, so there are many more bones in the pellets, and the bones have characteristic patterns of damage. Falcons also tend to break up their prey much more than owls do; owls usually swallow small birds and mammals whole.

More evidence for the identity of the predator comes from what it has been eating. Identification of the tiny, damaged bones of the prey is a specialised and time-consuming process. A large owl site will contain several thousand identifiable intact bones and fragments. But the volume is a bonus as well as a chore, since the large sample provides a more complete picture of the bird’s diet. Falcons, for example, consumed diurnal species such as skinks; owls nocturnal geckos and bats.

Once a deposit can be confirmed as having been made by laughing owls, analysis of the prey can begin. So far, our analysis has shown that the owl’s diet included 43 species of native bird, 3 species of bat (the two living bat species plus the extinct greater short-tailed bat), 7 lizards, a species of tuatara, 2 species of native frog and some fish. There were even some remains of a baby seal in one site.

After humans arrived, first the Pacific rat, then at least 10 species of introduced birds and two more rodents were added to the list. Or rather, the introduced species replaced native species that were lost as a result of the rat invasions and deforestation of the past 1500-2000 years.

The native birds included species from the smallest wrens up to kiwis and ducks. Wading birds on the riverbeds, seabirds breeding on the forest floor, even other predators such as the morepork and the extinct New Zealand owlet-nightjar were all fair game for the whekau.

Large beetles and weevils were also taken. The largest carabid beetle in the owl sites has a head capsule up to 10 mm in diameter, and is up to 50 mm long. Populations of this or a closely related species are found today only in small areas of the Southern Alps.

The owl sites have helped to fill the gaps in our knowledge of the natural distributions of these animals, since the present distributions are artefacts of modern influences. For example, very large geckos similar to Duvaucel’s gecko were regular items on the menu for laughing owls in North Canterbury. Now, such large reptiles are found no closer than small islands in Cook Strait.

Laughing owls nested in holes and crevices. Before the forests were destroyed, they would have lived, as moreporks do, in tree holes. Nests in cliffs sometimes became traditional sites. Owls lived in a cave on Takaka Hill, generation after generation, for over 10,000 years.

Holes were typically on north-facing cliffs, where the adults could sit in the evening and bask in the rays of the setting sun. They needed to be warm and dry, protected from cold, wet southerlies, and deep enough for the owls to retreat from daylight.

The typical clutch of two rounded, white eggs were laid on dry nesting material or directly on the powdery dirt of the chamber floor.

According to Smith, most clutches were laid in September and October, and the eggs were incubated for 25 days. The male of his captive pair fed the female on the nest as she incubated. The owls were quiet during the nesting period, except for the low call that the male gave as he brought in the food. That call was described as low and hoarse, and the female replied with a “peevish twitter.” Food for the nestlings was “large blackish worms” collected at the edge of swamps as they came to the surface at night. Later, they would be fed rats, birds and lizards.

None of the early observers records more than two eggs or nestlings. Owls often have larger clutches, and raise larger broods in years when prey are abundant. Perhaps the years of abundance were indeed past, and the food supply limited the production of young owls. More likely, the bird was like many other New Zealand species: slow-breeding and long-lived, in an environment with no mammalian predators. When the crunch came, with the introduction of species against which the owl had no defence, the reproductive rate was too low to cope with the high losses. The slide to extinction began.

[Chapter Break]

Even in death, the laughing owl is still part of the New Zealand scene. The effects of its nocturnal depredations have lived on in the habits of former prey, such as short-tailed bats, which wait until it is completely dark before leaving their roosts. Their chances of survival would have been slim if the owls could see as well as hear them.

The habits of some forest birds were also probably affected by the owl, but we know too little of the biology of too many of them for the details to be clear yet.

Most importantly, though, the owl deposits have given us the clearest view so far into the lives of the smallest members of the “lost” New Zealand fauna—those creatures which existed here before the foreign invasions that transformed the wildlife of this country. Beetles, frogs, lizards, small petrels, songbirds and bats were all taken as they presented themselves to the laughing owl’s watchful gaze and sharp ears, then returned to a single site, where the preservation of their indigestible remains was possible—indeed, likely.

Like most owls, whekau probably had small territories which they knew extremely well. We can be fairly sure that most prey would have been found within a kilometre or two of the roost or nest.

It was as if an animal vacuum cleaner was operating, sucking information into the dustpan of time. Examining the contents of that dustpan has proved to be one long treasure hunt.

But what of the vacuum cleaner itself? Can we be sure that it is no more? That it is just another obsolete model in the zoological panoply of these islands?

Once birds become very rare, it is easy to write them off. That is what happened to the takahe, thought extinct for 50 years until the memorable day in 1948 when a remnant population was discovered in Fiordland.

Even on small islands, species have avoided detection for decades. Given that owls are difficult to locate at the best of times, could a handful be holed up in some inaccessible limestone bluffs somewhere?

Persistent reports suggest some laughing owls might have hung on into the 1970s in the South Island. The late Archie Blackburn, a former president of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand, thought he heard one at Lake Waikaremoana in 1927. There have been supposed sightings in Fiordland and near Nelson, but the most convincing and continuous reports emanate from the drier eastern ranges and foothills.

One station owner is said to have kept an owl in his woolshed for some months in 1956 to control the mice. In the mid-1970s, possum trappers on another farm were advised to “take no notice of the owl calls.” A scientist working on New Zealand falcons found cavities on cliff faces that contained cast pellets that were too large to have come from even a large female falcon. Such pellets can survive for decades, but their presence in the same area as the sight and sound records suggest that a small population of laughing owls may have survived well after the supposed extinction date.

Reports based on calls are particularly difficult to verify. There are no tapes of laughing owl calls, and the written descriptions, such as those of Potts, point out that the calls resembled those of petrels. Petrels visit their burrows at night, and colonies of the larger species may have survived in a few mainland sites into the 1950s and ’60s. Sandy Bartle of the Museum of New Zealand thinks that calls heard in the western Ruahine Ranges in the 1950s were more likely to be those of the rare black petrel than of laughing owls.

Could the birds have survived? The answer is yes. There is a slim—a very slim—chance that the owls could yet have the last laugh.