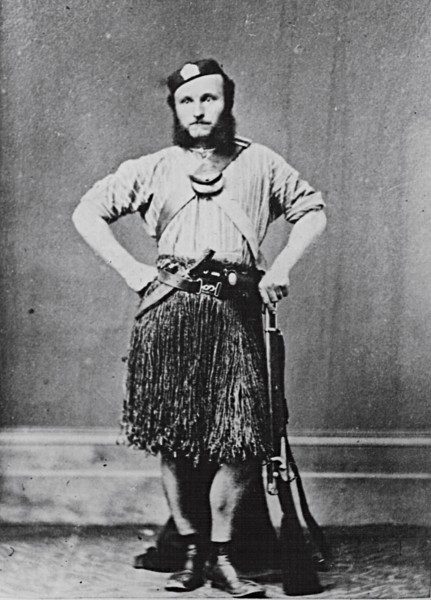

Corps of guides

Jungle Scouts of the Armed Constabulary

March 19, 1869. Stars twinkle through the trees: the Pointers, together with the Southern Cross, provide stellar orientation. Pickets cover the approaches. The bush camp is dotted with wharau (temporary shelters) and cooking fires, around which many warriors mill. All told the taua (war party) numbers 350 men, mainly Te Arawa and Whanganui, but there are also threescore Pakeha. There is laughter, also a tetchy Maori woman, one of the captives. A bittern booms from a nearby swamp. Bats flit overhead. At the closest fire the smell and sizzle of spit-roasted meat is all pervading.

At this fire Maori and Pakeha have come to watch. There is the commanding officer himself, a prominent ariki of a Whanganui tribe and also a highly decorated major. His mana is absolute. The constable alongside the major—a Scot picking at his pork trotter—will achieve fame in the 1880s as a Fiordland explorer. An unassuming pipe-smoking captain squatting on the far side of the coals will have fought in no fewer than 49 engagements in this war before he turns 26 in a year’s time. He will go on to become a stipendiary magistrate, and afterwards the New Zealand Government Resident at Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands. Many of the Maori present are literate, bilingual and commissioned officers in their own right. A big Pakeha lieutenant converses in te reo with them. This man will one day be adopted by Ngati Porou, attain the rank of full colonel, spearhead a two-year pursuit of Te Kooti, lead two Kiwi contingents in the Boer War, and go on to serve in the Great War. A laughing owl shrieks.

In cultured Victorian accents, gentleman officers discuss the imminent arrival of HRH the Duke of Edinburgh—Alfred, Queen Victoria’s second son. The colony’s first-ever royal visit! Two furlongs off a male and female kiwi call to each other, but no one cocks an ear: kiwi are a bob a bushel. The talk returns to the here and now: Titokowaru and the pursuit. The shimmering embers and red stones illuminate the faces of four men who will in the future win the New Zealand Cross, the colonial equivalent of the Victoria Cross. The onlookers—from disparate backgrounds—are united not only by their camaraderie and the fact they are veteran army scouts serving with, or enrolled in, the Corps of Guides, but by what they have come to see at this particular fire.

For this evening, whakapakoko nga upoko—the traditional process of smoke-drying human heads—has been reinstated by Her Majesty’s forces. Earlier, an umu was excavated, lined with stones and stacked with mahoe branches. A raging fire reduced the wood to embers, earth was heaped around the edge and the charcoal was raked back, exposing the red-hot stones to the night air. An enemy head, with orifices plugged, was then skewered with a green stake and is now propped low over the heat so that the neck faces downwards. Positioned thus, the head has been covered with fl ax mats and blankets to seal in the heat. The Whanganui tohunga periodically removes the coverings to wipe off the moisture and smooth the skin, and all eyes fi x upon that sizzling, dripping head…

The colonial army’s South Taranaki campaign against the army of Riwha Titokowaru was the nadir of the 1845–72 New Zealand Wars. By any standard these wars were small affairs. But what they lacked in scale they certainly made up for in brutality. Atrocity followed atrocity, with all and sundry implicated. Ancestral lands were confiscated, and scorched earth practices saw both kainga and township torched, water and food supplies spoiled, stock slaughtered and taonga looted. There were relentless pursuits and starvation. Hapu and iwi experienced degradation, segregation and exile. Pakeha and Maori women were raped. Not a few massacres occurred. There was torture, and there was execution. Maiming and death descended into the horrors of mutilation, cannibalism and head-hunting. As wars go it was nothing new.

[Chapter Break]

July 14, 2007 A scant 30 minutes ago, puffed and sweating, I was looking down from a ridge into the Upokorau Stream, where, at the confluence with the Ararata Stream, I believe the aforementioned head, and others, were smoke-dried over 138 years ago. My home in Eltham, south Taranaki, is barely 9 km away as the kahu soars. I was standing on a high point which was once part of the Taukokako Track, the inland Maori footpath connecting Tirotiromoana to the mid-reaches of the Patea River and the Wanganui hinterland beyond. A sharp south‑easter cut through my clothes, but I stuck it out with map and compass trying to make sense of the landscape.

Where once a 100,000 ha rata forest stretched from horizon to horizon, there is now just farmland and pines. Eastwards, though, stretching towards a frosted Mount Ruapehu, the lowland jungle remains. To the south-east lies the convoluted terrain traversed by both Titokowaru and his adversary Colonel George Stoddard Whitmore. Westwards, the Kapuni gas stack belches a wispy exclamation mark. Kapuni is very close to Te Ngutu o Te Manu, the kainga where Titokowaru won round one of the South Taranaki campaign with a haymaker to the solar plexus of the crown colony’s land-confiscation policy. Dominating all to the north-west is the majestic peak of Mount Taranaki. Sandwiched in the middle ground, between the mountain and my ridge overlooking the Upokorau Stream, is a patch of billiard-table-flat farmland. This is Rawhitiroa, once the legendary Te Ngaere Swamp, no less. Te Ngaere was to figure significantly in the closing days of the South Taranaki campaign. The first six months of the campaign were dominated by Titokowaru. Over that period the Maori general’s fighting force—not to mention his mana—swelled tenfold, and his undefeated army advanced towards Wanganui. Simultaneously, Te Kooti commenced guerrilla operations on the east coast, and suddenly the colonial government found itself waging jungle wars on two fronts. Titokowaru was deemed to be the greater threat. Colonel Whitmore, the army commander, reorganised his field force. One of the first things he did was form a small body of government scouts—the Corps of Guides—to act as pathfinders for a force largely reluctant to enter any jungle, let alone a Taranaki one. Experienced scouts were at a premium, as evidenced by a comment once made by Whitmore himself: “If the Ngatiporou are unavailable, and hounds to carry the trail considered to be improper agents for that purpose, I would suggest some Australian blacks should be engaged to supply what only very great practice can give to Europeans…”

[Chapter Break]

The corps of Guides was born in the bracken on January 25, 1869, the eminent historian James Cowan later recording: “That afternoon he [Whitmore] selected half a dozen of his most active men, some of them Constabulary, some volunteers, and as soon as night fell despatched them to the Okehu…” The field force under Whitmore was at the time about 10 miles (16 km) north-west of Wanganui township and probing for Titokowaru’s undefeated army (comprising Ngarauru and Ngati Ruanui iwi, Ngaruahine, Pakakohe and Tangahoe hapu, and many volunteers from Te Atiawa, Ngati Maru, Taranaki and Ngati Maniapoto iwi and various Waikato tribes), which was operating from the formidable Pa Taurangaika. Titokowaru was thought to have at least 500 warriors while Whitmore’s field force had 800 Maori and Pakeha. Whitmore advanced along the inland route—the west coast military road—between Wanganui and the Waitotara River.

Those first six scouts were placed under the command of cavalryman William Linguard, who had won the New Zealand Cross whilst reconnoitring Pa Taurangaika a few weeks earlier. Right from their first mission on the Okehu River it was obvious the Corps of Guides was different. For example, after shooting and skinning a horse, they fitted themselves with horse-skin moccasins. Hair on the still-warm footwear faced inwards. And quite apart from the de rigueur close-quarter hardware with which bush-fighters armed themselves, many Guides were dedicated two-gun men, a brace of holstered revolvers strapped round the waist. One Indian Mutiny veteran even carried:

…a two-ended steel knife, or dagger, of Afghan make, which he wore in a sheath at his back with a flap of skin over the top. One end of the dagger was a stiletto and the other was a double-edged cutting and thrusting blade, ground as sharp as a razor. It had the handle in the middle…he would throw it up into the air thirty or forty feet and catch it by the middle as cleverly as a juggler as it came whizzing down. He would stick a piece of paper on a post and, retiring twenty or thirty yards, hurl the shiny weapon at it and transfix the target in the exact centre, the knife quivering several inches deep in the post.

Alas, despite an exotic weapon and undisputed skill in wielding it, this particular Guide fell a few hours later to a crude bone-handled Taranaki tomahawk. He was the first Guide to be killed in action, and one of his fellows was badly wounded. However, despite the unit’s losses it foiled an enemy ambush in the wooded, gorge-like Okehu, which would almost certainly have inflicted heavy losses on the following main body of troops. Whitmore subsequently doubled the number of Guides to 12 and the advance continued.

In early February (despite being within a whisker of defeating the colonial field force yet again), Titokowaru’s army inexplicably abandoned Pa Taurangaika and withdrew towards the rohe of Ngati Ruanui, nearer Mount Taranaki. It was later discovered that Titokowaru had lost credibility on the eve of battle as a result of being caught with a subordinate’s wife. As Cowan quaintly put it: “The eternal feminine was at the bottom of it all. The chief of blood and fire, with all his mana-tapu, was vulnerable to the artillery of a dark wahine’s eyes and soft wahine blandishments.”

Forgoing the greater cause—defending south Taranaki/Whanganui tribal lands, kainga, whanau, forests, fishing grounds and waterways, not to mention mana and the right to self-determination—iwi and hapu broke away from the Ngati Ruanui general’s fighting core. His hapu and stauncher allies, however, perhaps 200 warriors, their women and children, stuck to their man, withdrawing into the bush and remaining mobile and elusive. There were further ambushes and skirmishes between his rearguard and Whitmore’s scouts as the latter launched recce after recce into the unknown surrounding bush. These missions were carried out not only by the Guides under Captain Frederick Swindley and Sergeant Christopher Maling, but also by the pick of the Armed Constabulary (led by Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas McDonnell) and the Whanganui, Ngati Apa and Ngati Raukawa iwi (led by Major Kepa Te Rangihiwinui).

The Guides experienced losses out of all proportion to their number—not only to enemy action, but also to exposure and exhaustion. Whitmore later recounted: “This little corps was limited to fifteen, but so many were the casualties that while I never had more than the fixed number available at one time, quite thirty were enrolled during the few months I had command.”

The next engagement of any size was at Otautu, several miles inland on the banks of the Patea River. This was the site of a temporary camp abandoned by Titokowaru after a hot gun-battle that saw six of Whitmore’s men, including yet another Guide, dispatched and 12 wounded. As Whitmore recorded:

He [Titokowaru] has escaped with comparatively light loss, though he has left seven or eight dead [The official count was four men. Were the others women?]…but he has lost all his camp, bell-tents, baggage, many arms, saddles, tools of every description, and even a very great many commonly used pipes, so great was the panic which must have taken him. A great quantity of food, fresh meat and potted meat, potatoes, clothes, blankets, almost everything down to Tomahawks and Maori spears, fell into the hands of our men.

After Otautu the campaign became a desperate jungle pursuit, which saw Titokowaru’s own elite—the Tekau-ma-rua or The Twelve—acting as rearguard. This was a body of veteran warriors selected by the rite of Whare-kura and, depending on the task in hand, might number anything up to 60 individuals. The Tekau-ma-rua staged an ambush near Whakamara, the major inland Pakakohe pa, winning an hourglass of time for Titokowaru’s main body encumbered with women and children. But the Guides, with Whanganui scouts and Te Arawa volunteers, led by Lieutenant Thomas Porter, pressed on and overwhelmed The Twelve. The pursuit became a rout. The Tekau-ma-rua, low on ammunition, were picked off as they defended stragglers.

At least 11 of Titokowaru’s people were killed and beheaded during this episode. According to Porter (via Cowan): “…they [the scouts] danced around the bodies like fiends, flourishing the tattooed heads of the dead by their long hair and shouting and yelling war-songs, and making hideous grimaces of the pukana. They were quite beyond control, mad with the lust of killing.” Porter tried to put a stop to the head-hunting by insisting the men take just the ears, but those concerned replied: “No, Witimoa said ‘heads’, and if he doesn’t get the heads he may not pay us!” Not wanting a .539-inch bullet in his posterior, Porter relented.

Titokowaru’s force was further reduced when the Pakakohe hapu broke away. With them went the infamous Pakeha-Maori Kimball Bent, who hid at Rukumoana, on the Patea River, for several weeks. Titokowaru himself was intent on getting to Te Ngaere.

The Guides, with Major Kepa Te Rangihiwinui at their head, followed the spoor. Whitmore’s despatch, penned four days later, described Te Ngaere and the action he took there:

I caused the swamp to be reconnoitred by a few Natives, and ascertained that the surface was treacherous…at length I decided to send a party across at a spot some hundred yards from an eel-pa where the swamp was narrowest, to gain the bank and entrench themselves, while with ladders and hurdles [the ‘ladders’, each consisting of three poles plus cross-sticks lashed together with flax and supplejack, were placed end-to-end to form a line] I enabled the force to cross the swamp without sinking by the regular track.

And so, four long days and nights after first sighting Te Ngaere, Whitmore’s field force finally reached the “island” in the middle of the bog. With little more in the way of sustenance than biscuit, bacon and brackish water over this period, and damp shawls and hollow rata logs in lieu of sleeping bags, and only the odd tiny fire, it was a commendable achievement. The Guides fanned out in the pre-dawn light and advanced ahead of the main body. When they hit the clearing they found non-combatants milling about and their quarry for the most part gone. In fact the lead scouts actually spied enemy stragglers disappearing into the swamp, heading west towards the Whakaahurangi Track, but no one wanted to risk drilling a “friendly” Maori by mistake as Ahitana’s hapu appeared from the surrounding flax, whare and fen. Some women and children approached the troops crying “Haere mai!”, and one brave soul even held up a white flag. To complicate matters further two pro-government Whanganui rangatira Kawana Paepae and Aperaniko—were found already in the camp with none other than the district’s resident magistrate, Mr James Booth Esquire!

[Chapter Break]

My eltham home is perched on the edge of what was once Te Ngaere. In fact, less than 5 km from my place—as the extinct crested mud-fish once wriggled—is Titokowaru’s camp site, and a little further east is the crossing point used by Whitmore’s field force. (The remains of the ladders and hurdles were found by the late Mr A. McLaughlin on his farm.) A local historian—Mrs Phyllis Every, now deceased—stated the swamp used to cover an area of about 2600 ha and that it was in fact two swamps, the northern (Te Ngaere) lying approximately 20 m higher than the southern (Eltham), the two being separated by a spoke of dry land running east–west. The two levels are plainly evident today as one drives along the Rawhitiroa Road. The spoke provided the escape route for Titokowaru, as it led directly to the Whakaahurangi Track connecting Waitara with the south Taranaki coast east of Mount Taranaki.

The Whakaahurangi Track once ran to within 150m of where I’m typing these words. The junction between it and the spoke of land was several hundred metres north. Where now one finds state house, “P” lab, barberry hedge, grass grub, windy cow and the road spoor of boy-racer rubber, there used to be a veritable Everglades, with rush, raupo, sedge, maire, kahikatea and silver pine. In the mid-19th century this bog carried a vast biomass, from bugs and bats through to bitterns, mudfish and eel, and possibly even a colony of kotuku. Alas, Te Ngaere is irrevocably gone—as was Titokowaru that March day in 1869. This time he had eluded his enemies for good. For Whitmore’s force, it was a bitter pill.

On April 4, the Corps of Guides led a column of troops along the Whakaahurangi Track to the north Taranaki coastline, a four-day, 74 km journey through heavy forest entailing no fewer than 68 stream and river crossings. At Waitara, the field force—with the South Taranaki campaign effectively over—boarded vessels and steamed off for a new campaign against Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki in the east, where the services of the Guides would be even more essential in scouting the route ahead.

[Chapter Break]

One month later, in early May 1869, Whitmore launched a two-pronged assault into Te Urewera. Ruatahuna was the destination, and Te Kooti the target. The left wing, comprising 421 mixed Maori and Pakeha troops under Lieutenant-Colonel J.J. St John, followed the Whakatane River upstream from the Bay of Plenty coast. The right wing, with 300 Maori and Pakeha men under Major J.M. Roberts and Whitmore himself, breached Te Urewera via the Rangitaiki and Whirinaki Rivers. All up, 13 Guides were employed on what would later become known as the Urewera Expedition.

Te Urewera was the domain of Tuhoe Nga Potiki, an iwi second to none when it came to jungle fighting. Most of the Tuhoe hapu were allied to Te Kooti, who at the time of Whitmore’s invasion was based at Pa Matuahu, on the shores of Lake Waikaremoana. Many Tuhoe toa were absent with Te Kooti, so it was left to a scratch force of warriors to cover all the approaches into Ruatahuna and stage what delaying actions they could to win time for the balance of the tribe to fortify the main pa, called Orangikawa, evacuate non-combatants, alert Te Kooti and organise hidden food caches. Under the circumstances they did exceedingly well, even as they were pushed back by the well-armed and determined government army. Small as the tribe was it still had teeth, and when it struck it was the Guides who were on the receiving end.

A Tuhoe ambush on May 7 killed one of the army’s best Guides, Lieutenant David White, as he was fording the upper Whakatane River at Te Paripari. Brave scouts pulled their leader out of the water and into cover as the leading divisions swept past, engaging the enemy. There on the river bank a service was read, and White was buried amid the manuka as combat raged around the small group. The Tuhoe ambush party fought it out and only withdrew when they were in danger of being outflanked.

The same day another Tuhoe ambush at Manawahiwi, 2 km upstream of Ngaputahi, engaged Major Roberts’ scouts. One of the Guides, Trooper Steve Adamson, later described what happened there: We came to a very narrow part…where a big landslip had come down and dammed up a part of the creek, and on the soft mud there ‘Big Jim’ observed the prints of naked feet. He was stooping to examine the marks closely, and was pointing them out with the butt of his gun to Captain Swindley, when all at once a shot came from the bush half a dozen yards away. Two or three shots followed in quick succession from our hidden foes, and ‘Big Jim’ received two bullets through the chest and lungs. Captain Swindley yelled to us to take cover, when a great volley came into us, crashing like thunder through the gorge, and Bill Ryan, a big man like the Maori, fell shot through one of his knees. He lay with his legs in the water. My brother Tom was shot through the right wrist, and another bullet struck one of the two Dean & Adams revolvers he wore slung on lanyards from the neck, crossing each other in front—we each carried two revolvers—and flattened out on the chamber, putting the revolver out of action; the blow cut his chest, although that bullet did not actually hit him. From whatever cover we could find we gave the Maoris a volley from our carbines. A dozen or so of the Hauhaus appeared and made a rush out upon us, but we took to our revolvers. They thought to dash in upon us while we were reloading our carbines. With our brace of revolvers each we fired heavily on them at close quarters and drove them back. Bill Ryan was lying partly in the water, and I saw a Maori with a tomahawk crawling through the bushes and around a log to despatch him. I quickly shoved a cartridge into my carbine, capped and fired, and nipped him in the bud.

Whitmore wrote of the fight a few days later: The march of the 7th…was mainly in the bed of a river, in a narrow defile. The crossings were however more numerous, being no less than fifty-five. The Corps of Guides led with the greatest caution, but in such narrow passes it is impossible to avoid receiving the first fire… At length the enemy opened fire, and after a smart skirmish was driven off, probably with some loss, as a mat shot through and saturated with blood was picked up, and a man fell in another place close to the leading guides. Three of our men were hit, all of the Corps of Guides. One of these was Hemi, a well-known Native from Taranaki, much respected in this force, and who wore a watch and pistol presented to him by the officers of the 43rd Light Infantry, for his gallantry on many occasions when acting as their guide. This poor fellow died the same evening…

On the day I visit the scene of the Manawahiwi ambush, a discarded bag of KFC bones thrown from Highway 38 marks the spot. Pockets of native hardwoods cling to steep gullies and, on the bank opposite, scruffy farmland, plantation forest, tree fern and bracken cloak the land. Further downstream, in the Okahu Gorge itself, where the Guides scouted all those years ago, little has changed. Lichen-draped tawa and rimu forest, waterfall, canyon, slippery boulder, log jam, landslide—all conspire to make the path treacherous enough without the further danger of an enemy volley. At Te Whaiti, stands of columnar rimu, kahikatea and miro dot the confluence of the Okahu and Whirinaki Rivers and still attract flocks of kereru. The old-growth podocarps witnessed the Guides’ advance in 1869, and it is quite likely that the three or four kereru Hemi, a.k.a. “Big Jim”, is said to have speared the day before he was killed met their end in some of these very trees.

Away from the main road, the Urewera back country today still largely retains the bush cover that was there during the 1869 campaign. Logging has been restricted to the flatter, more accessible valleys. All told nearly 300,000 contiguous hectares of primary forest allow a person on foot to get a real feel for the wilderness the Guides encountered.

Despite ambush and counter-ambush, a battle at Pa Orangikawa and several skirmishes about Ruatahuna, Whitmore’s army failed in its objective of killing Te Kooti and destroying his Ringatu fighting force. The government troops withdrew to the coast. In the colonel’s words:

The total loss of the enemy it is difficult to say exactly, but twenty bodies were found… Fifty prisoners have been taken. Immense quantities of provisions have been consumed or destroyed, and every kainga of note, except the settlements of Maungapowhatu [sic] and Waikare[moana], have been destroyed. The prestige of this unknown and difficult country have been lessened, and for the first time in their history the “Tuhoe”…have seen a war party enter their country, pass completely through it, sit down and occupy their principal settlement, and leave it without serious loss. (In fact a Ngapuhi taua under Pomare had invaded Ruatahuna in 1823 and could have made a similar boast.)

[Chapter Break]

After a short break, the Corps of Guides, along with No. 2 Division of the Armed Constabulary, boarded a vessel at Matata and steamed south to the Wairoa district. The detachment made its way overland to Onepoto to reinforce the army of Lieutenant-Colonel J.L. Herrick, then engaged in building an inland naval flotilla on Lake Waikaremoana. In the end no shots were fired during this ineffectual operation, although the scouts themselves did undertake reconnaissance missions into the forests about Onepoto. Historically the Guides next resurface at Tokaanu, in the central North Island, in September 1869, participating in what would later become known as the Taupo Campaign.

This saw the main government field force under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas McDonnell, a.k.a. Fighting Mac, once more fighting Te Kooti. It was a campaign of open expanse, spyglass and horse, conducted from early September until the end of the year. In snow-smothered tussock under the shadow of an erupting Ngauruhoe, three battles were fought as well as an ambush or two launched. Once again the Corps of Guides was instrumental in providing intelligence, and—almost certainly mounted—ranged to all points of the compass, sweeping and glassing the open country of the Central Plateau and the headwaters of the Whanganui River, and skirting Pureora Forest and both sides of the Waikato River. Like Te Kooti, Fighting Mac was operating mainly inside the boundaries of theRohe Potae—consecrated turf of the dreaded, albeit neutral, Ngati Maniapoto and other Kingitanga tribes, who, before throwing in their lot with any one side, awaited developments between the antagonists. Both Fighting Mac and Te Kooti were skating on thin Taupo ice.

It was the Guides who found Te Kooti, with Horonuku Te Heuheu, paramount ariki of Ngati Tuwharetoa, entrenched at Te Porere. After the climactic battle at that prepared position, which saw Te Kooti wounded and 37 of his men killed, the Ringatu leader vanished into the hinterland. From that day until early January 1870 the Guides worked to relocate their quarry, and none risked his life more than Sergeant Maling. Maling had by this time assumed command of the unit, and recce by recce he quickly became a legend for his escapades in hostile country. For his efforts he was later awarded the New Zealand Cross. Finally, in December, two scouts, Te Honiana and Wiremu, located Te Kooti at Taumarunui, but before Fighting Mac was able to react his quarry again disappeared.

Sometime in mid-January 1870, the Ringatu force turned up at two settlements in the Bay of Plenty. The kainga at Kuranui and also Pa Tapapa were located on the edge of the Mamaku Plateau, where the Ringatu allies—the Pirirakau and Ngati Raukawa tribes, Ngati Porou exiles, a hapu under Kereopa Te Rau, and two Arawa hapu (Waitaha and Ngai Tapuika) under the leader Hakaraia—had established themselves. Bolstered by these staunch warriors, and having recently been resupplied with ammunition, Te Kooti was more than ever a force to be reckoned with. He still had his fighting disciples, known as the Whakarau—The Sixty—made up for the most part of ex-Chatham Island prisoners. These were veteran fighters, mounted and armed with Enfield rifles, the latest breech-loading carbines, sawn-off shotguns (tupara), revolvers, swords and the ubiquitous tomahawks. Woe betide any Guide who blundered into their path!

Yet some of the Guides did just that. Over two days of confused and inconsequential fighting around Pa Tapapa on January 24 and 25, 1870, one Guide was mortally wounded. On February 3, no fewer than three were killed and a fourth mortally wounded in a brilliant ambush staged by the Whakarau at Paengaroa. These scouts had been leading a second government field force under Lieutenant-Colonel J. Fraser inland from Tauranga. Afterwards, the Ringatu ambush party broke away and vanished. Despite such losses, jumpy Guides with twitchy trigger fingers strove to re-establish contact with their foe, roving the woods between Tauranga, Rotorua and Taupo, as well as continuing to escort orderlies between Fraser, Fighting Mac and the Armed Constabulary Commissioner, St John Branigan, in Cambridge.

Despite a sterling effort from the corps, Te Kooti eluded the closing net of the two government armies. Chased south of Rotorua by Lieutenant Gilbert Mair and his Te Arawa Native Contingent, the Ringatu leader managed to regain the Urewera wilderness in February, where he was to remain at large for another two-and-a-bit years. From that point on the native contingents (Ngati Porou, Te Arawa and Whanganui) took over the pursuit, and, apart from the notable exception of Private Thomas Adamson, who scouted for Major Kepa Te Rangihiwinui on his March 1870 expedition, the Corps of Guides found itself at a loose end. In June of that year, after 18 months on active service, the elite unit was withdrawn from the theatre.

Man for man, its achievements and casualties exceeded those of any other colonial or imperial unit—including the famed Forest Rangers—on active service over the entire 27-year span of the New Zealand Wars. The Guides were a bitter-sweet concoction of discipline, pragmatism, motivation, efficiency, aggression and spirited loyalty; yet their corps had no fancy badge, no flag, no Latin motto, no mascot, and was never officially gazetted. No section-sized unit in the entire British Empire could boast five Victoria Cross holders to match the Guides’ five recipients of the New Zealand Cross, as well as a close association with a further five. Despite these facts, the Guides the definitive Legion of the Lost—have over the years faded into historical obscurity.

And what of those trophy heads taken during the Whakamara pursuit? At least four of them are known to have reached Colonel Whitmore before the advance on Te Ngaere. Whitmore had earlier put a bounty on the enemy, offering to pay £10 a head for chiefs and £5 for ordinary men. When those trophies rolled out of their flax ketes onto the floor of his tent, he was forced to pay up. Subsequently, he stipulated there would be no further payouts for decapitations, and, interestingly, the smoke-drying incident never raised its ugly head in any of his military despatches.

Finally, how did that first royal visit work out? The Duke of Edinburgh arrived in Aotearoa in April 1869, blissfully unaware that the crown-colony army had been engaged in whakapakoko nga upoko. Even as Prince Alfred’s loyal subjects toasted His Royal Highness at one gay event after another, the troops of Whitmore’s field force were still lopping off the odd Ringatu head in Te Urewera. Of course, the Guides were nowhere to be seen.