Tramspotting

Discarded 50 years ago, a handful of old trams have been pieced back together by enthusiasts, and have now become a feature of the city.

Early morning, and the Christchurch tram barn is pleasantly cool. The gleaming paintwork on the old tramcars’ wooden panels shows the liveries of once-proud companies—and these are still gracious conveyances.

But the start of the working day for a motorman is far from glamorous.

Armed with a slopping bucket of window-washing gear, a clipboard and broom, I weave between the sleeping tramcars. My first duty is on Tram No. 152, the Boon, named after the city’s former tramcar builders, Boon & Co. It’s a 44-seat double-saloon car with clerestory roof. Coupled to the tram is a four-wheel trailer, No. 115, the Duckhouse, named after the antics of yesteryear’s conductors, who used to duck in and out to collect fares.

These are beautifully crafted vehicles, built for the Christchurch Tramway Board (CTB) in the first years of the 20th century, an era when craftsmanship favoured the ornate and was a matter of pride.

I haul on long ropes attached to the 600 V DC overhead poles, and, to clean the windows, stretch across varnished

seats of native wood that seem more in keeping with a luxury yacht than 21st century public transport.

Exteriors are Paris green and white with silver and red pin-striping—the colours of the CTB. Design features were probably modelled on stylish horse-drawn vehicles. Even the air compressor’s intermittent pumping is subdued, like tram chatter. “It’s nice to see you, Roy. Did you sleep well? I certainly did.”

The tinkling foot bell makes a friendly sound. The air gauge for the brakes sits at 80 pounds per square inch. Turning indicators blink, and the communications radio, a necessary concession to modernity, beeps.

As other trammies fuss around No. 178, the Brill, the atmosphere becomes even more companionable. One of two Melbourne cars, No. 244, and the diminutive No. 11, formerly of the Dunedin Corporation, will hit the tracks later in the morning. No. 411, the second Melbourne car, will rest until evening, when it will take to the streets as a stylish restaurant.

Time to smarten up uniforms. Trousers are black with red piping, the same as worn by old-time Christchurch motormen, and we don peaked caps. Black ties contrast with crisp, freshly laundered white shirts. We collect money bags, tickets and clippers. High roller doors rattle open, and, with a clanging of bells, the day begins on New Zealand’s only 21st century street tramway.

My trammie colleagues, a mix of men and women, have taken on the job having pursued a variety of other careers—as teachers, a university lecturer, a fire chief, a farmer, a backpackers’ proprietor, an environmental consultant, metropolitan bus drivers and a locomotive driver. Five years ago I tossed in my long-time job as a newspaper reporter to become a rookie motorman and willing partaker in front-line tourism.

The training, all in-house, was intensive, and the prospect of driving an intimidating rail vehicle amongst pedestrians as well as road traffic was challenging—alarming, even.

Tramway tutor Joe Pickering is a retired teacher and long-time member of the Tramway Historical Society. He patiently teaches wannabe drivers the idiosyncrasies of the veteran tramcars, each of which requires different driving techniques. At present, three motorman licences are needed to operate the entire fleet of five tramcars and two trailers. Driving tuition includes instruction both in basic electrical mechanics and in the safety requirements of the city loop.

Once mastered, the trams are fun to drive. Notch on the power, release the air brake, increase speed to full series, then parallel, notch off, and apply the air brake.

No. 11, the Boxcar, is the tramway’s equivalent of Thomas the Tank Engine. She rocks along the tracks on a single-truck bogie. No. 178 is so easy and smooth. No. 152 has a complicated air brake that takes time to feel confident with. No. 244 is easy to handle but does the most damage if it runs into something it shouldn’t.

“Driving trams is basically simple,” Joe tells his students. “But to drive them well takes some skill.” Since the tramway is a tourist attraction, it is important to be able to start and stop smoothly. Good drivers get to drive the restaurant tram.

As they learn to master the antics of these painstakingly restored rail-borne vehicles, drivers are inescapably reminded that they are one-off originals.

[Chapter Break]

The Reinstated tramway has recaptured Christchurch’s urban-transport past. Electric tramways made their debut in the city on June 5, 1905, taking over from horse-drawn and steam trams, which had trundled up and down the streets since 1882. Being faster than their predecessors, they contributed to an increase in suburban development, and such was the rate of spread that within a few years there was a network exceeding 80 km of track. In its heyday, Christchurch had a tramway comparable with Melbourne’s extensive system.

Between 1905 and 1927, Boon & Co. built more than 70 tramcars, along with numerous trailers, at its Ferry Road works. Christchurch was one of nine New Zealand cities to build tramways.

As a kid I frequently boarded the trams, until, worn out, outdated and neglected, the last of them rattled to a stop on September 11, 1954. I had ridden the Port Hills trams to the Sign of the Takahe, the Riccarton trams, and, most memorable of all, the Sumner trams, immortalised in the lines of poet Denis Glover. In those days Cathedral Square was a shunting yard for trams.

The present city loop agreeably snares the past and present within its 2.5 km track. It introduces tourists to the city’s English aspect, embodied in the meandering Avon River and a number of striking buildings in the Gothic Revival style, several of them the work, or at least partly the work, of Canterbury architect Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort. This is the best of Christchurch, of particular note being Christchurch Cathedral (designed by Sir Gilbert Scott but with touches from Mountfort, who supervised construction), The Arts Centre (formerly the University of Canterbury, co-designed by Mountfort and a number of other local architects), the Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings (all Mountfort’s work), Christchurch Botanic Gardens, the Antigua Boatsheds, Christs College, and the huge Hagley Park, with its curious model-yacht club on Victoria Lake.

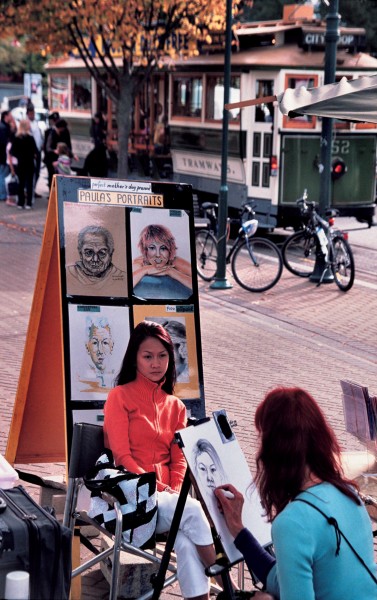

The tramway has ensured a lively existence for The Arts Centre and for the stylish new Christchurch Art Gallery, opened in 2003, as well as inspiring a new culture of inner-city markets, buskers and colourful businesses, especially in New Regent Street, with its Spanish Mission architecture.

In addition, three heroic figures featured on New Zealand bank notes are associated with the tram tracks along Worcester Boulevard suffragette Kate Sheppard, politician and land reformer Sir Apirana Ngata, and scientist Lord Rutherford of Nelson. Stories about each of these abound. An attraction of the motorman’s job is the freedom to spin intertwined versions of history and folklore while rattling round the tracks.

There is a memorial to Kate Sheppard, who appears on the $10 bank-note, on the river bank close to the Worcester Bridge stop and the statue of Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Sheppard’s suffragette movement appealed to American writer and humorist Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain when he visited Christchurch in November 1895.

Sheppard used a wheelbarrow of sorts to carry more than 30,000 petitions to Parliament. In September 1893, with the help of two Liberal backbenchers who voted with the opposition, the electoral-reform bill granting women the right to vote was passed into law. The rebels were an embarrassment to the government, especially to Prime Minister Richard Seddon.

In his book Mark Twain in Australia and New Zealand, Twain quotes the 1891 census, which gives the population of Christchurch as 31,454. Of those, 6313 men voted in the November 1893 election, along with 5989 women voting for the first time. Twain estimates 85.18 per cent of the 109,461 women registered to vote nationally went to the polls, proving that women were not indifferent to politics, and he applauded their right to vote in New Zealand:

“Man has ruled the human race from the beginning—but he should remember that up to the middle of the present century it has been a dull world, and ignorant and stupid…”

Well, that’s something for us present-day trammies to smile about, especially knowing we work for a company keen to promote a multicultural workplace along with equal opportunities for women.

Sir Apirana Ngata, on the $50 note, and Ernest Rutherford, on the $100, attended Canterbury College during the 1890s. John Campbell, author of Rutherford: Scientist Supreme, believes the two students were good friends. Apirana Ngata, from Te Araroa, on the East Cape, was the first Maori to graduate in New Zealand, completing a BA in political science (2nd class honours) and, three years later in Auckland, an LLB. He is recognised as the father of biculturalism in New Zealand.

Ernest Rutherford was the father of nuclear physics. In 1917, as a research director at Manchester University in England, he became the first person to split the atom. Subsequently, in 1937, he became the only New Zealander to have their ashes interred in London’s Westminster Abbey. Among other honours, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1908 and received 20 or so honorary doctorates from universities around the world. Yet when a TVNZ news team recently set up their cameras outside Christs College and asked passers-by what Rutherford was famous for, most had little idea. His academic life is superbly rendered in Rutherford’s Den, behind the Arts Centre Clock Tower tram stop.

[Chapter Break]

Across rolleston avenue the clock tower, close to the entrances to Christchurch Botanic Gardens and Canterbury Museum (another Gothic Revival design by Mountfort), a circular bronze plaque is set into the pavement at the foot of a statue of William Rolleston, a former superintendent of the province of Canterbury. It catches my eye as I negotiate the tight curve from Worcester Boulevard into Rolleston Avenue, and is inscribed with one of those typically visionary statements uttered by pioneers of colonial New Zealand:

“We have sketched out in our imagination a handsome central street running through the city, terminated at one end by the College and the Gardens—at the other the Cathedral in the Central Square.”

These words are not, however, attributed to Rolleston, but to Henry Sewell of the Canterbury Association, who stood on this spot in 1853. At that time, Sewell, who was to become (briefly) New Zealand’s first prime minister three years later, was standing amongst swamp, tussock and cabbage trees—prominent features of 1850s Christchurch. Another decade would pass before work began on the cathedral, while the college (Christ’s College) was yet to arrive on its town site and the museum wouldn’t open until 1870, seven years before the university. The plaque was unveiled to mark the opening of Worcester Boulevard by Mayor Vicki Buck on September 7, 1991.

Worcester Boulevard, including a wide pedestrian path stretching from Cathedral Square to Canterbury Museum, was an attempt to link Christchurch public facilities and create a cultural precinct that would appeal to tourists. A heritage tramway with eye-catching veteran tramcars was part of the council’s plans for the boulevard, and part of a wider effort to make Christchurch a worthy tourist destination rather than a mere entry point to the wonders of the South Island. It was, however, the brainchild of members of the Tramway Historical Society, who had been restoring tramcars and operating a museum tramway at Ferrymead Heritage Park since the 1960s.

The painstaking scraping-away of old paint had revealed original tramway liveries, and the society had gained many skills rebuilding wood-and-sheet-metal tramcar bodies. While some power machinery and bogie wheels had to be sourced from tramways around the world, including those in Melbourne, Brisbane, Brussels and Nagasaki, some, including the New York Peckham maximum-traction bogies for the Boon, were made from scratch and without the benefit of engineering drawings. This was a world-first for a tramway museum.

Max Taylor, the last general manager of the Christchurch Transport Board (formerly the Christchurch Tramway Board) before it amalgamated with the city council, smiles when he recalls the beginnings of the Tramway Historical Society.

“We had a redundant wing in Moorhouse Avenue where there were stored a couple of old tram trailers that looked more like hen houses by that stage. I hadn’t been with the board long when youngsters, including Bruce Dale and John Shanks, started making visits to scrape off the old paint. If anything they were a bit of a nuisance. But they were persistent to the stage where they could preserve the old Christchurch Brill tram No. 178, which now runs on the city loop.

“They did this magnificent restoration at Ferrymead by begging, collecting, borrowing—I don’t think they stole—pieces from around the world. The board soon held members of the Tramway Historical Society in high regard, and we were prepared to assist them whenever we could or do work at favourable rates. As a last gesture, when the CTB was amalgamated with the council in 1989, we deeded to the Tramway Historical Society all the property they had on loan from the former board.”

That property included a Kitson steam tram built in 1881, an 1887 American-built horse tram, and two AEC-built heritage buses. In retirement, Max Taylor joined the Tramway Historical Society, serving as its president and treasurer.

[Chapter Break]

Laying the tracks for the city loop began in Worcester Boulevard in 1991. While on my rounds for the newspaper I would frequently stop to watch the construction and was intrigued to see how the rails were set in concrete. But many Christchurch people, having little confidence in the $6 million venture, would shake their heads and walk past mumbling about absurdities. It was “the influence of over-enthusiastic council tram-buffs pushing their agenda,” wrote one correspondent to the Press.

When a prominent architect presented a somewhat exaggerated sketch depicting the overhead power supply as an ungainly arrangement of pylons and cables, the project temporarily stalled. A serious proposal to operate a horse-drawn tram service instead was dismissed when it was pointed out that horse droppings and the accompanying pong would be even more repellent than overhead wires. The doubters were largely appeased when the pylons were redesigned to be more pleasingly ornate than originally intended.

The rebuilt tramway opened with great fanfare on February 4, 1995, and more than 10,000 people enjoyed the novelty of a tram ride over the three-day Waitangi weekend.

Although the city council backed the project, it didn’t plan to operate the tramway itself but to lease it to a private company as a sort of franchise operation, creating income for both parties. Shotover Jet of Queenstown was the inaugural lessee, since superseded by the present incumbent, Wood Scenic Line, which also runs the Mount Cavendish gondola and the Avon punting operation. The tramcars remain the property of the Tramway Historical Society and, like the track, are leased to the operator.

Tramway staff are regular paid employees. They usually work a shift of seven to nine hours, which equates to 13 to 18 trips round the loop. A few rounds are spent working as conductor on a two-person tram, providing a respite from the live commentary (the motorman’s job) but involving instead a flurry of ticket selling while keeping an eye on the timetable. Communication between conductor and motorman is with bells—two to start, three for an emergency stop, when, for example, someone decides to board or alight while the tram is moving. The signals are much like those used by the old-time trammies.

[Chapter Break]

Weekends can be the busiest as well as the best days on the trams. Local people and their families turn out, joining the tourists in the city. Weekends also bring the buskers to The Arts Centre cultural precinct. Among them is Lord Livingston (actually Chris Devious), Christchurch’s only fidgeting “stone” statue. He’s so convincing that even seagulls land on his head. Chris says he’s been a busker since 1988, having performed in the Australian outback, at university campuses in the United States and at orphanages in Romania. He moves in slow motion, enticing children with sweets, posing for photographs and feigning falling in love with passing women.

Ellie, displaying a sign that reads “Donations make me happy,” plays saxophone and sells CDs. And there’s Rex and his well-trained Polly. Rex lost an arm when he crashed his motorbike. He found Polly, a sort of terrier–border collie cross, in the dog pound facing a foreshortened future. Man and dog teamed up, and Polly now rides a skateboard and performs impeccably to the crowds. People lean out of the tram windows, firing off their digital cameras. As Rex says: “Polly keeps the wolf from the door. And if the wolf knocks on the door, I’ll invite it in and teach it a few tricks.”

Discovering new things to ensure a lively commentary is a constant challenge. Walking the city loop occasionally on days off certainly helps. Chatting with the cathedral staff and climbing the spire for a bird’s-eye view of the trams can be as enjoyable as trying the latest beers from the Dux Deluxe brewery, visiting Johnson’s old grocery store in Colombo Street, discovering the World Peace Bell in the botanic gardens, or catching up on the latest exhibitions at the art gallery.

An occasional visitor to the tramway is Geraldine Bowman, probably the sole remaining conductor from the days of the CTB. Now in her 90s, she turned out impeccably dressed in her trammie uniform in September 2007 when the Brill celebrated 100,000 city-loop circuits—250,000 km in just 12 years.

Geraldine joined the tramways in 1942, when her husband was a prisoner of war in Germany. She lived at Sumner and, when on the early shift, rode her bicycle 17 km into the Moorhouse Avenue tram depot for a 5.55 a.m. start. Predictably, her first run was on the Sumner tram.

“At the end of a day working on Christchurch trams I would go home at night thinking, ‘I’m not going back there again.’” She laughs. “But you always did.”

She chats about trammies being cautious on the Hills tram while on early-morning trips in winter. Descending Hackthorne Road on icy rails was sometimes more than a little frightening.

Winter was always worst. “When you had to pull down the poles and change them around, water would always run up your sleeves. Sometimes, sparks would be flying everywhere.

“And there were things trammies were forbidden to do. One was to step from the moving tram to the trailer. It was highly dangerous but we did it. If you didn’t, then you would never get all the fares. Then you would be in trouble when you got into town.”

The late Rita Curzons was another old-time trammie. I chatted to her back when I was still working as a reporter. “I loved the work,” she told me, “it was just up my alley.”

She hit it off well with the motormen, who, unofficially, taught her—a conductress—to drive. She recalled the day when she got into trouble for driving a tram without a certificate. On the way into town, at Redcliffs, the motorman, Jack Lumis, collapsed with a heart attack and she took over. A deputation from the company met her in Cathedral Square and was going to punish her with dismissal. But when it was recognised that her actions had saved the motorman’s life, she was congratulated instead. And she did get to drive trams lawfully during the war years, when several women took over the jobs of motormen.

Rita continued as a conductress for about nine years after the war—until her husband told her it was time she had a rest.

“‘One man in the family is enough,’ he told me. I used to wear the trousers, literally. But I wouldn’t mind if some of those tram days came back.”

Trams rattle across the Avon twice on the city Loop. Even though the river is considered to impart a certain Englishness to the city, there are contradictions. The weeping willows lining the grassy banks are believed to have grown from cuttings brought to New Zealand in 1838 by French whaler François Lievre, said to have obtained them from trees sheltering Napoleon’s grave on the island of St Helena.

Mark Twain knew the trees’ supposed origins and thought them “the stateliest and most impressive weeping willows to be found in the world.” He attributed their superiority to “the line of a great ancestor”.

As for the name of the river, it does not come from the Avon of Shakespeare’s hometown. It was bestowed in the 1840s by Canterbury pioneers William and John Deans after the Kilmarnock Avon, which runs into the Clyde in their native Ayrshire, in Scotland.

The tram stop in New Regent Street, amid the colourful Spanish-style facades, is a popular place to alight. When opened on 1 April, 1932, the street was described by Mayor Sullivan as “the most beautiful street in New Zealand”. Its architect, H. Francis Willis, was sent broke by the project.

George, the Swiss-born proprietor of the Swiss Café, says New Regent Street has been consistently tenanted in full only since the tramway opened. Brought up in a Lausanne orphanage, George was the only Christchurch retailer proudly to display an Alinghi poster in his window during the 2007 America’s Cup regatta.

I am intrigued by the Groom Room for Gentlemen. The business is owned and staffed by women, as I discovered while relaxing in an old barber’s chair, one of three recovered from an Invercargill barber’s shop, as Margo Flanagan’s nifty scissors attacked my overgrown mop.

The Groom Room captures all the imagined nostalgia of an old-time barber’s shop, with its “candy” pole, memorabilia and a pampering service, nicely complementing the tramcars trundling by every few minutes. “Guys relate well to being groomed by women,” says Margo. “We’ve never had a guy apply for a position here,” she laughs. “And, although our clients are typically men, a woman would not be turned away—providing she was happy with a short back and sides. I have my hair cut here.”

In the mirror I note that Margo’s haircut, with long twisted strands, is anything but a short back and sides.

Cut-throat razor shaves and facial massages are listed on the price board. And the experience can be enhanced by sipping freshly brewed coffee or even a warming port.

“The guys enjoy being totally pampered when lathered up with traditional Trumper’s soap from the UK and soothed with hot towels and a facial massage,” Margo says as she trims my eyebrows, nose and ear hair and tidies my small beard.

“The best of it is having a groom room in a beautiful heritage street with tramcars. Often we are asked to turn the chairs to face the window so our clients can watch the trams trundle by.”

[Chapter Break]

The last stop before Cathedral Square is Cathedral Junction. This is a large, impressive glass atrium emulating an English railway station of the Victorian era, and the brainchild of John Britten, better know for his beautifully crafted motor cycles. Britten had taken over his father’s property-development business and was keen to create an elegant shopping mall for the tourist tramway, but he died of melanoma in September 1995. The partly demolished site remained in limbo until it was redesigned by the Buchan Group, with the incorporation of many of Britten’s concepts. In the meantime the trams carried their passengers through the wreckage, known irreverently as Little Bosnia.

I arrive back from a coffee break to find the Boon, plus trailer, waiting at the junction. Both cars are jammed full, as they would have been in their heyday, mornings and evenings, transporting workers to the city and home again. Off-peak, the tramcars would have carried well-dressed women on their city shopping sprees. Eager children would have pressed their faces to windows, smearing the glass and risking a scolding from the conductor. Well, some things don’t change.

Wheels squealing, their flange-contacting surfaces not having been greased since heavy rain earlier in the day, the Boon negotiates a tight curve round the Citizens’ War Memorial, where dawn services are held on Anzac Day. The intriguing bronze figures here are the work of sculptor William Tretheway, who studied at the Canterbury School of Art. They are modelled on real people who lived in Christchurch during the 1930s. The decidedly sexy figure of Victory is bending a sword. Is she about to break it, to signify the end of all wars? The memorial was unveiled in 1937, not long before WWII.

And so the day continues, with a nod to the statue of John Robert Godley, founder of Canterbury and Christchurch.

Come evening, I get to drive the restaurant tram—without overturning one glass of wine. But I get an earful from the chef for knocking him off his feet while descending the track into Victoria Square with a touch less sedateness than desirable.

The atmosphere at night, with calm on the streets and the city’s lights glowing, is quite different from the bustle and glare of the day. Especially enchanting are the art galley’s glass facade, the discrete illumination of the museum, and the colours of the triple-sphere Ferrier Fountain before the steps to the town hall. Cold air rushes through the cabin door I choose to leave open. Despite being isolated from the diners, I hear the murmurs of companionable chatter and enjoy the wafting aromas. No whirring microwaves here. Everything is cooked in the compact on-board kitchen. Unfortunately, I don’t get to share in the repast. When feeling peckish, I dig into my Spartan lunch box and pour instant coffee from a Thermos.

At the end of the day, trammies usually feel they’ve done their dash. Manoeuvring amongst traffic and pedestrians while being a tour guide and trying to be accurate with tickets and change requires constant concentration. In 18 circuits we’ve covered a distance of just 45 km—at the pace of an arthritic turtle. But the trams are not about speed. They are sedate and gracious relics of a less frantic time—and possible harbingers of what might be to come.