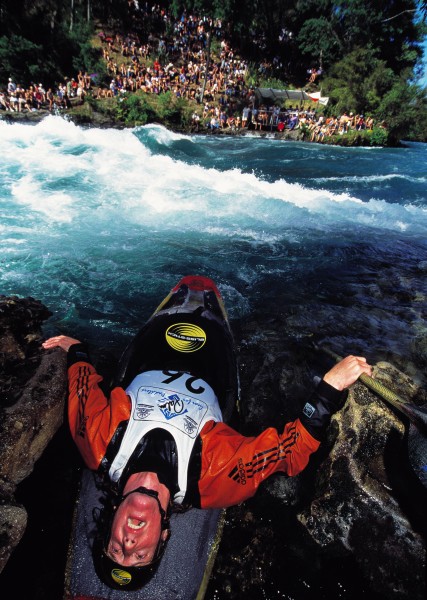

Battling the white dragon

Every two years, the world’s elite freestyle kayakers gather at a chosen river and compete in a championship whitewater rodeo. In 1999, it was New Zealand’s turn to host the event—at the Fulljames Rapid on the Waikato River. For months prior to the championship, competitors practised at the site to get the feel of the water and to learn the idiosyncrasies of its standing wave.

Driving down A dusty, dead-end road through parched December farmland, I find it hard to believe I’m going to watch a world-class sporting event. The location seems completely incongruous with the event title: World Whitewater Freestyle Kayaking Championships.

Even before I arrive I can feel the thumping musical beat that is the customary soundtrack to modern extreme sports.

The car park—at any other time considered busy when there are just a dozen vehicles—has overflowed to a second paddock and includes a couple of hundred roof-racked cars.

People speaking a range of foreign languages congregate around vehicles displaying product and sponsor endorsements. The sporadic roar of a crowd coming from somewhere beyond the barbed-wire fence drowns out the music and an American-accented commentary.

I follow the sounds to the banks of the Waikato River. Below me, overlooking the Class HI rapid known locally as Fulljames, or Ngaawapurua, hundreds of people are jammed on to a series of tiered river terraces. Some have climbed trees for a better view and others are standing on rocks just centimetres from the 300 cumec (cubic metres/ second) watery freight train that is speeding past.

All eyes are on a kayaker surfing the standing wave in the middle of the rapid. The kayaker spins 360 degrees and then tumbles into the folding white crest of the wave, known as the “pillow.” The ends of the kayak cartwheel through the air, then, impossibly, the boat and its owner squirt out of the pillow like a bar of soap and back on to the green part of the wave.

The crowd roars its collective appreciation. Unified by their mirror shades, surfwear, bizarre haircuts and body piercings, they pump their arms in the air, encouraging the hydro-acrobat in the rapid to even greater feats.

This is the sport of freestyle kayaking, and these paddlers are the best in the world.

[Chapter break]

Historically, competition kayaking was restricted to flat‑water sprinting, slalom and downriver racing. The “playboating” community existed, but regarded the idea of organised competition with disdain.

However, with every new technological improvement came new practitioners who refined and codified the sport, until, to the disgust of some paddlers, freestyle kayaking soon had international rules, points, times, regulations, judges, appeals and even drug tests.

In the early days of the sport, kayaks were four metres long and only one step evolved from a hollowed log. Tricks were restricted to standing your craft vertically—an “ender”—or perhaps throwing your paddle away and showing control by just using your hands. To add variety, paddlers tried anything from juggling balls while surfing the wave to shedding their clothes.

Now, at world-championship level, the best competitors have set moves, like a gymnastic routine, designed to gain maximum points in difficulty and variety within a set period of time.

Unlike land-based freestyle events such as skiing or skateboarding, where the substrate remains constant, a river wave constantly changes. The precious “fold,” which keeps the kayaker on the wave, is always flexing and surging, sometimes there; sometimes not. The green wave stands steep one moment and levels off the next, and random ribs and boils break up any uniformity that might start to appear.

Competitors talk of the feel of the wave beneath them, the feel of the hull sliding or grabbing as they move around searching for aquatic features to work with; as they look for patterns in the chaos.

Not only are they trying to read the water but also control boat, paddle and body—all of which can move three-dimensionally at any time. Somehow these athletes hold it all together to perform a range of moves with names such as verticality, ollie, blunt, reo, clean, splitwheel, green grind and cartwheel.

The tools of the trade dictate the performance level. Over the past 10 years kayaks have evolved from a plastic log with a hole in the middle (with loglike performance characteristics) to hydrodynamically designed, radically shaped two-metre trick machines.

Modern freestyle kayaks have flat, broad, low-volume ends—which are easy to “initiate” into the river to start a manoeuvre—and a high-volume pod around the torso of the paddler for buoyancy. The hulls and edges are designed to make the boat “slippery”—to reduce the surface tension holding the boat in the water, so it can move on its own axis.

The fit of the kayaker to the kayak is also critical. Like the transfer of angle from ski boot to ski, the transfer of body torque to boat is crucial for sending subtle messages to the craft. Competitors have their kayaks fitted to them like a glove—or a vise. Releasable winch straps are used to ensure that every nuance of body position is transferred to the kayak—but don’t expect to get out in a hurry.

[Chapter break]

The world championships are held every second year, with a “Pre-Worlds” competition in between, allowing kayakers to experience the venue and make design modifications to their craft for the following year.

The event is divided into heats, semis, finals and sudden-death super-finals. Competitors get a warm-up period on the water, then, at the signal of the head judge, they have 60 seconds to “shred” the way c with as many moves and tricks as they can manage. In each round they have five chances on the wave to amass points.

On the day I arrive at Ngaawapurua, the finals are just getting under way. The pressure has built to boiling point. The rides are increasingly important to competitors as they focus on making it to the super-final.

Some stretch and warm up on the bank before crushing legs and feet into their impossibly tiny craft. Others spin lazily with the currents and boils in the holding eddy—a large backwater which provides an easy ride back to the wave.

Prior to competing on the wave, paddlers have to move upriver to the final collecting eddy, formed by one defiant finger of bedrock which pokes into the river and offers a micro pocket of respite from the speed and turbulence. This eddy wriggles, bounces and surges like a sack of excited piglets, making pre-ride preparations difficult.

Here paddlers go through their mental rehearsal and build-up. Some focus inwards and mime certain moves and body positions. Others do breathing exercises, and a few yell, wave their arms around and chant strange incantations to the river gods.

The judges give the thumbs-up for the next competitor. It’s show-time, and playing to the crowd is just as important as pulling the moves. Enormous speakers compete with the roar of the river to thump out the paddler’s favourite music, chosen to get the crowd grooving to the beat and creating the party scene synonymous with the modern extreme-sport performance

The paddler eyes up the surging shoulder of water. Even getting on to the wave is no easy feat. The speed and angle of the kayak have to be precisely chosen to accelerate from a standing start to paddling upstream against a current moving at around 18 km/h. Miscalculate and you will be flicked downstream in an instant. This sometimes happens—even at world-championship level.

Once over the shoulder, the paddler surges on to the green part of the wave and places a blade in the water. A slight lift of the upstream edge breaks the surface tension on the hull, and the kayak comes to life.

Eyes, head and torso twisting in symphony, the paddler drives the kayak into a 360 spin. With the boat spinning well from the torque provided by the body twist and initiating stroke, the competitor removes the paddle from the water and holds it up for the crowd and judges to see. The judges call rapid-fire points to the scorers for the flat spin and the “clean” (controlling the spin without paddle strokes). The paddler is washed into the folding crest and sets up to spin in the other direction. More points, more cheers from the crowd.

Flat spins are one of the easier freestyle moves. Competitors use them at the beginning to get the feel of the wave and gain initial, but low-scoring points. Extra points are added for alternating spin direction and doing cleans.

The paddler is feeling good now, and starts eyeing the folding pillow. The nose of the kayak drops downstream and the boat picks up speed across the river. It looks like the paddler is going to shoot right off the wave, but with precision timing a rotating stroke is jammed into the upstream flow. As the kayak hits the fold, the paddler unweights the boat—as in a ski turn—and throws body weight forward and upstream.

For a split second the boat is almost completely clear of the water. Now the nose comes around and lands back in the flow. With a lightning-fast re-trim of the hull, the kayak continues the spin in the flat plane. An aerial blunt to a flat spin is good; the paddler knows it and the crowd knows it—lots of pumping fists and “Yeaaahh!”

Time for the big-scoring but high-risk moves. Returning to the fold, the paddler looks for an exact angle in the horizontal and vertical planes. Using precise strokes and body positioning, the nose is buried just enough to stand the kayak vertically. Too much and it will bury off the wave; too little and the move won’t happen.

Caught by the current, the nose whips underneath the paddler faster than is consciously controllable, so the next movements are based on reflex and intuition. Two, three, four, five times the paddler vertically switches ends. Like the hub of a wheel, the paddler’s body stays steady while the kayak spins.

The minute is up, but this has been a superb ride and could have won the championship had it been in the super-final. The paddler will have to repeat or improve the performance when the time comes.

[Chapter break]

Up in the carpark, kayaks are scattered across the grass, paddle jackets are drying on the fences and the beer stand is doing a brisk trade. Here and there, competitors grab a few hours’ sleep in pup tents or in the backs of station wagons, while trade exhibitors hawk the latest designs in boats and accessories.

Knots of paddlers talk about trips to exotic rivers, about new moves they are working on, maybe their plans to try a descent on the West Coast after the rodeo is over.

After nightfall, the dusty summer haze will give way to starlight and the clean, cool smell of the country, but few will notice. Too hyped to sleep, the crowd will move in unison to the trance music into the small hours of the morning.

Tomorrow the river warriors will go out again and do battle with the white dragon.