Banks Peninsula

This gnarled hand of land is a fist of defiant ruggedness in the monotonous flatlands of coastal Canterbury. Yet sharp topography has done little to protect the forests that once clothed the ground, of which the three wind-blown matai seen here are typical remnants. The human inhabitants of the peninsula tend to display a similar stalwart individuality.

Between bites of croissant and sips of café au lait, from a table on the tiled terrace where Rue Jolie meets the bay-side esplanade, I watch the French flag flying above Akaroa’s volcanic beach. The tricolour is faded by the sun and wind, and disrespected by seagulls. It has clearly seen better days. But still, whenever the breeze sends a puff of air into it, unrolling the blue and the red, and the white mouth in between, it oddly and uncannily reminds me of French lips pouting with that unmistakeable irreverence. All that’s missing is the equally characteristic shrug of the shoulders and perhaps the words “Mais oui, pourquoi pas? Why not? It was a good idea. Pity that it did not work.”

Pity, indeed. Oh, Monsieur Langlois, if you had only hurried! How different things could have been, how drôle! We could have had topless beaches and chocolate from Côte d’Or, bœuf and coq au vin instead of pies and KFC, champignons not mushrooms, vineyards thick as native forests, scholarships at the Sorbonne. The New Zealanders from the North Island would be coming down to visit us, in our beautiful Nouvelle-France of the South, crossing Cook Strait the way the Brits traverse the English Channel, likewise looking for a place in the sun. Oh, Monsieur Langlois, instead you have left us with a vestige, a relic, a nostalgic remembrance of things past. Wonderings on what could have been.

Admittedly, being a closet Francophile in a country with a consensus distaste for things French is a tough proposition. The trans-Channel rivalry is almost genetic, its roots deep and tenacious no matter how far from its source it is transplanted. Who, in any case, can forget the Rainbow Warrior and President Chirac’s defiance at Moruroa, after which even buying ink cartridges for a French-made fountain pen was seen as an act of national treason? But in Akaroa, a quaint riviera town nestled in the nook of an ancient volcano, a holiday-makers’ hotspot and an international must-see, a closet Francophile can safely come out. Moreover, she or he can find kindred spirits, which is what originally attracted me here.

To get to my café table—where I work each morning in true Proustian fashion, sniffing pastries and filling the pages of notebooks—I walked down Rue Grehan, turned left into Rue Lavaud, and passed La Croix and Rue Balguerie. I saw des maisons and des hôtels, places with names like Ça Bouge and La Folie Jolie, even a garage offering réparations d’automobiles. I took my time, for this enclave of French connection is tiny and largely notional. Still, my morning promenade was long enough for the novelist’s perpetual question, What if?, to take hold in my mind. What if the French had made it to the South Island before the English? What if M. Langlois had driven his ship the way the French usually drive—with little regard for what speed they are going and overtaking everyone in their way?

I shall not argue the validity of the act. Arriving in an already inhabited land; planting a flag on its shores; claiming it as one’s own or buying it with trinkets; inviting the natives to join the new colony—this was standard operating procedure for acquiring large tracts of land when Captain Jean François Langlois, an adventurous and enterprising man of 29, anchored his whaler, Cachalot, in the shelter of Port Cooper (the old European name for Lyttelton Harbour) in August 1838.

This was the heyday of whaling, when the stock of ocean giants seemed inexhaustible and France alone had some 60 ships prowling the South Pacific. At that time, France did not yet have any colonies down under—no New Caledonia, no Marquesas or Tahiti or parts of Vanuatu—but Banks Peninsula was already an established and strategically located international port of call, busier than Wellington or Nelson. With its many sheltered coves, each with its own river and strip of beach between rocky headlands, it offered safe, attractive harbourage close to the whaling grounds and centrally located in the South Island. As Langlois saw it, the peninsula was an ideal piece of antipodal realty, a “foot in the door” to colonise l’Ile du Sud, a perfect base for the French conquest of the South Pacific.

Langlois knew that King Louis-Philippe was particularly keen to acquire a far-off place to which to deport troublemakers. The Chatham Islands were to be the new penal colony, the French version of Van Diemen’s Land (renamed Tasmania in 1856), from which even the most determined would be unable to escape. The British were already firmly established in the North Island, but the South was still there for the taking. And it was so much like home—it had its own Alps, Provençal landscapes, agreeable climate. What better place in the world was there to build Nouvelle-France?

[Chapter-Break]

Langlois Set to work. At the end of the whaling season—which ran from May to August, when right whales came inshore to calve he entered into negotiations with local Maori. On August 2, 1838, some 11 chiefs drew crosses and moko (the equivalents of signatures) on a piece of paper offered by the Frenchman.

The exact procedure Langlois followed is unclear, and it has been postulated that he simply collected the signatures on a blank piece of paper on which “details” were to be added later. Be that as it may, he supposedly bought a fair slice of Banks Peninsula from its owners. He got a bargain, too, outlaying 1000 fr. (£40) with a down-payment in goods: a woollen and an oilskin overcoat, six pairs of trousers, a dozen hats, a pistol, two pairs of shoes and two shirts. Try offering that to a real-estate agent next time you’re buying a farm. With his legal document secured, Langlois immediately sailed back to France to lobby for the formation of a New Zealand company, to be modelled on the British East India and Dutch East Indies Companies.

These were decisive days for New Zealand, but the French didn’t prove assertive enough. When, after two years of politics and planning, Langlois brought out the first group of some 60 colonists aboard Comte de Paris, he was too late. The Treaty of Waitangi had been signed, and the British annexation included the South Island as well as the North. When, after a six-month voyage, Comte de Paris anchored in Akaroa (the name translates as Long Harbour) on August 17, 1840, it was greeted by the sight of the British man-of-war HMS Britomart, and a Union Jack flying over the harbour.

There was a brief stand-off, during which the Maori chiefs claimed they had not received payment, but the French settlers were eventually allowed to stay, and beside the harbour, renamed Port Louis-Philippe, they surveyed and built a town—the first in Canterbury. They were an industrious lot and they prospered, developing farming and sawmilling and, later, boat-building and fishing.

Over time, they intermarried with and blended into the predominantly British community which came to surround them with the result that almost all traces of their ethnic and cultural heritage disappeared. All that remained of the grandiose dream of New France was a handful of street names and a token tricolour.

The croissants and café au lait made their appearance only recently, when tourism promoters hit upon the marketing ploy of resurrecting the French connection. All things considered, Banks Peninsula, and with it the rest of the South Island, was probably never destined to become another Quebec. But then again, if only Langlois had hurried up…

[Chapter-Break]

The French called it Presqu’Ile de Banks—Almost Banks Island and, indeed, even the ever-meticulous Captain James Cook, with no time for closer investigation, decided that the steep volcanic mountains were so different from the otherwise flat and sandy coastline they must be an island. The navigator promptly named it after his botanist Joseph Banks and sailed away, driven by agendas of empire.

The fault-finders still like to point out Cook’s rare cartographical error; however, when you examine the geology of the peninsula more closely, you realise Cook wasn’t so wrong after all. He was merely late, and not by much, either.

For most of its existence, Banks Peninsula has indeed been an island, formed between eleven and eight million years ago by the eruptions of two volcanoes, whose craters today form Lyttelton and Akaroa Harbours. At its tallest, the island rose some 1500 m above sea level, and it is only in the last 20,000 years that the Canterbury Plains—an accumulation of alluvial detritus and loess from the Southern Alps—have spread out to sea and joined the island to the mainland.

Since its earliest inhabitation by humans, the peninsula must have been considered prime real estate—relatively handy to the Arahura and Taramakau greenstone lodes, offering two natural harbours and numerous sheltered bays, easy to defend, and with a rich harvest of seafood to be had on all sides. Ngati Waitaha settled it, then Ngati Mamoe, then Ngai Tahu, and all left ample evidence of their subsistence there, making the entire peninsula an archaeologist’s treasure trove.

Leaving the café society of Akaroa, and with it the bel air of French influence, I climb the tortuous road towards the summit ridge and the monumental rocks that stand like bastions along its crest. Below, the peninsula sprawls out in all directions. From the air it looks like a giant scalloped leaf with its stem planted in the mainland, but from the ground it resembles overlapping hands. The ridges reach out to sea like thick, gnarled fingers, and there are hints of webbing between them where beaches and dunes have formed. The hills are the colour of bronze, and single-lane gravel roads labour up and down them in hairpin zigzags. There are homes perched like eyries, each with its million-dollar view of bays and sea. One of them, along the track that descends into Okains Bay, belongs to Murray Thacker, collector extraordinaire.

The Thacker family has been farming the hills above the bay since 1850, and though Murray has maintained the tradition, his real interest has always lain in archaeology, and over the years he’s spent most of his spare time fossicking and treasure-hunting at innumerable local sites and digs.

The peninsula was once heavily populated, by tribal standards at least, and Okains Bay used to sport three major pa and associated kainga (villages), each with some 200–400 inhabitants. Then, around 1825, one woman’s transgression against custom led to a bloody five-year war in which every single pa was destroyed and the peninsula’s population shrank from 3500 to a mere 400. Subsequent raids by the musket-wielding Te Rauparaha in the 1830s decimated the population even further and led to almost complete extermination of the local tribes.

Murray’s passion soon spawned a collection of artefacts that he deemed too large to remain hidden away in private. Thus, with the help of his neighbours, he rebuilt the former Okains Bay cheese factory, once famed for its cheddar, converting it in the process into an exquisite museum. As I explore its several pavilions, including the meeting house Whakaata—constructed with strict adherence to Maori protocol—one thing is immediately clear. You could probably find rarer or more precious exhibits elsewhere, but they wouldn’t tell as true a story as those displayed here, for this is a collection of practical things gathered by a practical man. It reveals more about the daily life of Maori and the challenges they faced than anything else I’ve seen. It opens one’s eyes wide and clear to the ways in which they went about their very survival.

The collection of fishing gear is particularly telling—no fancy stuff, just the tools to get the job done. There are wooden hooks with interchangeable bone-carved barbs, some with paua inlay. There’s an array of sinkers, from small woven flax bags that could be filled with stones to chunks of volcanic rock with eyes drilled in them that could possibly double as anchors. There’s also—and here my angling heart leaps at the recognition of forethought and design—an aho, a 70 m fishing line fashioned from dressed flax and tapered to a fine point, much like a modern fly-line.

Other exhibits are even more technologically advanced: a freshwater-mussel dredge to be towed behind a canoe; eel traps and elaborately woven nets, coarse ones made from supple-jack, finer ones from kiekie roots, and finer ones still from mangemange; bird perches with built-in snares; and, most ingenious of all, a drinking trough for pigeons at which, in order to quench their thirst, the birds couldn’t avoid putting their heads through one of the nooses arranged in two precise rows over the water. Seeing it all, my mind begins to conjure visions of an Arcadian existence, with kai moana and free-range poultry for easy picking, but Murray quickly dispels the illusion.

“We have fairly idyllic notions of the Maori life,” he says. “We think of fishing and hunting and rustic camp scenes, but the truth is their life was incredibly tough. Shellfish, for example—a staple diet of the coastal tribes—contained a lot of sand and grit, which wore people’s teeth out. In all the skulls we’ve found by excavating old pa sites, the teeth have been worn down flush with the jawbones. I’d estimate that an average lifespan was about 30 years.”

The museum’s grandest project, and Murray’s pièce de résistance, is two full-sized waka, intricately carved, still seaworthy and ready to go, on launching trailers improvised from the chassis of a 1941 Ford truck. Murray found the first waka, the totara Kahukaka, dilapidated and abandoned, quietly rotting near the Wanganui River, not far from Harihari on the West Coast. He bought it and had it railed to Christchurch, but there disaster struck.

“Do you still want it?” the trucking contractor inquired uneasily over the phone. “She may not be worth bringing over.” It transpired that the waka had been accidentally dropped and had splintered into some 60 pieces.

“She was a sorry mess,” Murray recalls. “Essentially, it arrived in Okains Bay at the back of a banana truck, all smashed up, like a pile of firewood. We built a shed over the wreck, then five of us worked two weeks solid to make her look like a canoe again.”

It took another five years to fully restore the hull. In 1978, carvings sculpted from local totara by master-carver John Rua were added. Next came a complete set of manuka paddles. Finally, the 62 ft (19 m) craft was officially launched.

The project had awoken the shipwright’s spirit in Murray, and as soon as Kahukaka had been completed he set out to build another waka, this time from scratch and from locally available materials.

“We were learning by doing,” he says, “and so we made her too narrow and tippy. We had to cut her lengthwise with a chainsaw to add a totara floor, to widen the hull. After that she was good as gold.”

They rode two-metre waves in her on the way to an appearance in Lyttleton Harbour, and she was as sure as a Stabicraft. Both waka are ritually launched and paddled every Waitangi Day—a spectacle, I’m assured, not to be missed.

[Chapter-Break]

I leave Murray, his museum and his farm, where Hereford cattle graze in leisurely fashion on dramatically steep ridges that plunge into the sea, and return to my vantage point on the summit. I live in a landlocked place on the edge of the Southern Alps, so the vast expanses of turquoise ocean draw me with the magnet of novelty. Banks Peninsula is all about the sea. The sea shapes its existence and moods.

Many years ago, in one of the rocky southern bays of the peninsula, I was initiated into the realities of scuba diving as the more laissez-faire choose to pursue it. I was fresh out of a comprehensive PADI training course and had found work in Golden Bay diving for geoducks (Panopea zelandica), a species of large bivalve that buries itself deep in the seafloor. There, working on a boat with a compressor and a hookah system, I met Mitch, who must have been diving since Jacques Cousteau was a young lad.

Mitch (I use an alias for reasons that will soon become apparent) had a bach on Akaroa Harbour, and he invited me to dive with him there. One day we puttered out in a tiny dinghy and anchored in a bay where volcanic walls plummeted into the sea.

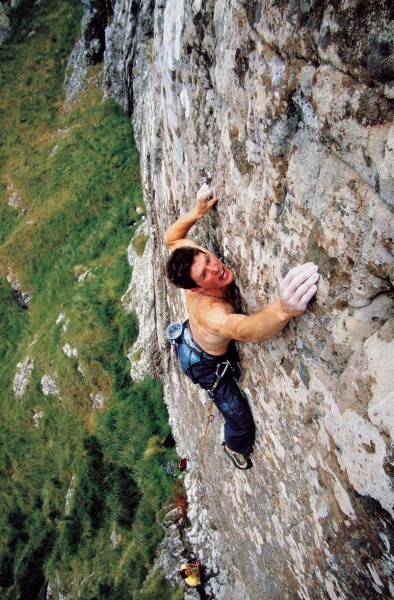

Forget the PADI protocol, forget about never diving without a partner. Mitch disappeared into the depths, and I was alone as I dropped down the face of one of the walls through a milky surface layer of water. Further down, I passed through a thermocline and the water cleared, revealing an austere and gloomy landscape below. The wall bristled with delicate anemones, and tiny fish defended their patches of territory at the close-up sight of an intruder.

An hour later I found Mitch at a depth of 30 metres, pillaging the sea floor for crayfish. His catch bag was almost full but I saw him squirm into a cave entrance in pursuit of another cray. The opening was low and narrow, and Mitch’s tank kept catching against the rock and impeding his progress, meaning the cray managed to keep just out of his reach. To my astonishment, he took his tank off, laid it on the bottom, sucked a deep breath from his regulator and swam into the cave, leaving his gear behind. His legs kicked frantically, as if the cave were swallowing him.

An age later Mitch reappeared, wrestling a cray so large it almost needed a nelson to handle it. It wouldn’t go into the bag, not without a fight at least, so Mitch calmly pinned it down with one hand and knee, reached for his air supply with his other hand, took a breath, then finished the brute job of stuffing the cray into the bag. Only then did he put his regulator back into his mouth and slip into the harness of his aqualung. He checked his air, then his watch, and nodded contentedly: there was still time for more. And so the poaching went on.

I was new to the country and new to the sea and had no idea of the legalities of what he was doing, of catch and size limits. Or why we had to take the “quiet” road home. Only later, over a dinner of crays, bread and beer, did Mitch confess uneasiness. The crays were much smaller these days than when he’d started selling them. Less numerous, too. Still, the undersized ones tasted better. More tender, you see.

Fortunately, much has changed since those rapacious and ignorant days two decades ago, and today large parts of the waters around Banks Peninsula are protected. A marine-mammal sanctuary, stretching from Sumner Head near Christchurch to the mouth of the Rakaia River, and extending four nautical miles out to sea, encloses the peninsula’s entire coastline, protecting Hector’s dolphins, as well as seals and penguins, from the dangers of set nets. Most exemplary of all, however, is Pohatu Marine Reserve in and around Flea Bay, south of Akaroa.

I reach the bay after another single-lane hairpin climb and descent, and with only just enough daylight remaining for a brisk scout around. The bay is keyhole-shaped, and its mountainous rim—the perimeter of the reserve—is heavily guarded with some 300 traps arranged in several lines of defence. The results of this predator-control regime are instantly noticeable. Within minutes of leaving my truck I see a yellow-eyed penguin only a few metres away, then a coterie of white-flippered penguins porpoising in the kelp beds.

Flea Bay is the largest mainland breeding ground of the white-flippered penguin (the local subspecies of the little blue), and the home of Shireen and Francis Helps looks like just another, albeit oversized, nesting box among the hundreds they have built here since the late 1980s. The penguins’ breeding season lasts from September to October, but some birds arrive to claim nest sites as early as April.

“They are petulant and intolerant neighbours; they fight and quarrel, and that often delays their breeding,” Francis tells me as we watch the penguins from the trail high above the shoreline. “They can get so carried away with their brawling they miss the breeding altogether, because they produce only one clutch of eggs each season. As with any endangered species, the number one priority is to simply breed them up.”

The penguins’ domestic antics—the never-ending soap opera punctuated by acts of rampant sex and violence are a source of constant amusement to the Helps and their many visitors and volunteers. But do not let the veneer of jest detract from the magnitude of the project and its achievements. While elsewhere, in the peninsula’s unprotected colonies, the numbers of penguins are declining at an alarming rate, at Pohatu the Helps have achieved a six per cent annual increase, which, as Francis says, is about as good as it can get. More remarkably still, the entire effort was a home-grown and self-funded initiative in its early years, although more recently a variety of organisations have assisted. Shireen runs sea-kayaking and snorkelling tours around the reserve, and there is no shortage of wildlife enthusiasts wishing to see the penguins up close (the best viewing opportunities being between September and January).

“It’s really not rocket science,” Francis says matter-of-factly. “You take care of the habitat, the wildlife takes care of itself. Once we’d cleared the area of mammalian predators—some of the big tomcats we shot were up to 10 kg, cunning and trap-shy, like miniature tigers—we saw results straightaway, and not just with the penguins. Moreporks, falcons and frogs have returned; you can hear the birds at dawn.” He pauses and grins. “You know, we’re supposed to run a farm here, but this wildlife stuff is so much more fun.”

Shireen and Francis were both born on the peninsula, and Francis got his land the time-honoured way: he an his brother Steven worked for their father for wages and once they saved up enough, borrowed to buy their own farm, with the old man providing collateral. But he also saw the times were changing.

“Farming was tough, we suffered years of drought, the prices were low, and we were barely managing to hold onto the land,” he recalls. “One day in 1988, we were having one of our usual whinge-and-moan get-togethers when someone suggested, ‘Why don’t you do something else, capitalise on the area’s spectacular scenery, build a coastal walking track or something?’”

It sounds obvious now but at the time it was a revolutionary idea, and the farmers grabbed it as drowning men seize a life-saving rope. Trails were already in place, they just needing sprucing up, connecting and marking, plus a few bridges. Within months the work had been done, and the private Banks Peninsula Track came into being, the first such venture in the country. With its wild coastal scenery and private beaches, its easy access yet relative remoteness, and its singsong motto, “Four nights, four days, four huts, four bays”, it was an instant hit.

“We underestimated what we had,”here Francis says. “It took a few hundred trampers to tell us how amazing it all was. After that we started to look at our home with different eyes.”

Today the track attracts some 2500 walkers each year, providing steady income for eight local families, as well as helping to protect a section of the peninsula’s coast as wildlife habitat. It also has a most unusual manager.

On the way to Flea Bay, coming down from the Summit Road towards Akaroa, I passed a lone cyclist who was slowly, almost defiantly, pedalling his way up the hill in low gear. He had a bushy white beard and carried two blue panniers bulging with groceries. His face was composed, his breathing steady. From my own cycle-touring days I recalled that Banks Peninsula had the steepest and most unrelenting uphills in the country. This climb was particularly brutal but the man showed no signs of undue exertion. I waved, and he waved back, making his bike wobble momentarily. He regained his balance and continued on his way without missing a beat. He may as well have been walking along the Akaroa promenade.

The cyclist, Francis tells me, was Hugh Wilson, a well-known New Zealand botanist, a director of the Banks Peninsula Track, caretaker of Hinewai Reserve, and one of the peninsula’s most eccentric identities, commonly referred to as “the saint on the hill”.

“He travels everywhere on his bicycle, wouldn’t get into a car if you tried to drag him into one,” explains Francis, who also passed him on the road ear lier in the day. “For him, Christchurch is a ‘car-infested swamp’, and he always cycles to go there, taking the long and hard way, over the summit.”

This, no doubt, explains the relaxed breathing and the coast-tocoaster legs.

Wilson is known for his detailed and precisely illustrated reference books on the plants of Mount Cook and Stewart Island, but his biggest and most ambitious project to date has taken root in the Otanerito valley, just over the crater rim from Akaroa. From an initial 109 ha in 1987, Hinewai Reserve has grown tenfold, becoming a showcase of native-forest restoration. It is estimated that virtually all of Banks Peninsula was once covered with forest, of which less than one per cent remains today. In 50 years’ time, if Wilson has his way, Hinewai will be 99 per cent native forest again, and the formula for this apparent miracle is as unorthodox as the man himself.

At first glance, much of the valley in which Hinewai nestles appears overrun with gorse. Ulex europaeus, like a kind of barbed-wire hedge run amok, flowering for much of the year and swallowing the land faster than you can pump Answer or Weedazol at it, is the bane of many a New Zealand farmer. But listen to Wilson talk about gorse and you might think your ears are playing tricks on you, for he is a passionate exponent of it as a nursery plant, not to be sprayed but left to grow undisturbed. Gorse, he maintains, can expedite the regeneration of native forest, although it is rather flammable. Under a protective canopy of gorse, many native seedlings thrive, before, after a few years, growing through it, at which point they start to shade it. Eventually they deprive it of the sunlight it demands and completely replace it. A gorse plant has a lifespan of about 20 years, at the end of which, being rich in nitrogen, it makes useful fertiliser. Thus, Wilson says, the conversion from noxious weed to second-growth native forest is achieved with minimal human interference.

“We basically create the conditions whereby nature can just get on with it,” Wilson once said in an interview. “She’s been practising for billions of years, and is far better at it than we are.”

Hinewai is certainly growing proof of those unhurried yet unfailing powers of metamorphic self-balancing. All the same, gorse as an ally! Can you think of a more glaring oxymoron? Swap your spray gun for a watering can. Help the cursed thing do its noble work. But then, if it works, why not?

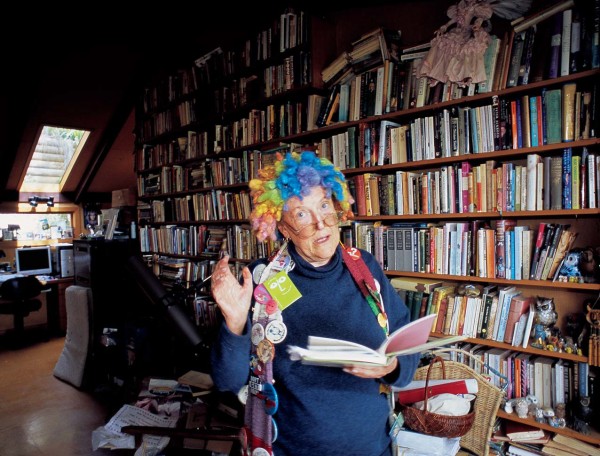

If Wilson is the peninsula’s saint the do-as-I-do inspirer of environmental ideas and the conscientious objector to the ways of technological modernity—then Josie Martin is Akaroa’s answer to Salvador Dalí, bringing the don’t-take-it-all-so-seriously message to those who listen and many who won’t. When we meet at her Giant’s House above town, she’s wearing a mop of blue hair, harlequin-style clothes and an impishly irreverent grin, all of which support her artistic credo, lifted from T.S. Eliot, “Dare to disturb the Universe.”

With Akaroa as their epicentre, the disturbances she has created have sent ripples several times around the world. As a painter, sculptor and mosaicist, she has held art workshops in Italy, staged some 26 solo exhibitions and attended art residencies wherever the arts flourish. Everything about her is an explosion of colour—riotous, exuberant colours that storm your senses and burn lasting after-images into your mind and memory.

She shows me the house, originally the residence of Akaroa’s first bank manager, now a live-in art gallery for her prodigious creativity. Besides innumerable paintings there is papier-mâché furniture, a room devoted to roses, a bed built inside a boat anchored to the floor (against stormy dreams, perhaps) and a toilet with a piano (with its own seat, separate from the WC).

When Josie bought the house the grounds had been neglected, but with training in both art and horticulture she has turned the land into a kind of magic garden and a piece of art as well—a manicured maze of hedges, shrubs and flowerbeds peopled with larger-than-life mosaic sculptures.

“I was digging in the garden and found a buried pile of broken old china,” she recalls. “It was too beautiful to throw away and I saved the shards and used them to make my first mosaic. It went on from there.”

Nowadays, tonnes of concrete and glass later, house and garden are a stage for frequent poetry readings and music recitals, as well as a profitable bed-andbreakfast and a place that attracts garden tours and TV shows. And all the while, Josie is positively burning with new ideas, restless and fidgeting, making sure each passing minute gets a full 60 seconds’ worth of her attention.

We sip coffee on the Giant’s House veranda, and though dozens of questions pose themselves in my head, none seems appropriate, necessary or relevant. This is a visual world where pictures and forms speak volumes and need no explanations. Besides, Josie, as colourful as if she’s just stepped out of one of her paintings, wears an expression of provocative mischief, as if it’s all a grand joke and she’s checking whether I’ve got it or not.\It’s only later, when I reflect on the experience, that I can put my feelings into words, aided by one of my favourite dissenters, a decidedly outside-the-square thinker—Terrence McKenna.

McKenna remains best known for his excursions into, among other matters, ethnobotany, but he was also a highly knowledgeable and eloquent art connoisseur and historian. To his way of thinking, just as sailors of old explored beyond the boundaries of the known world, opening new routes and discovering places hitherto unsuspected, so artists push back the frontiers of the mind to reveal fresh ways of thinking and seeing.

When McKenna delivered his thoughts in a lecture at a Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, he lamented the lack of originality in modern art, its constant recycling and regurgitating of ideas, the nihil novi attitude that there is “nothing new under the sun”. Had he met Josie Martin, I thought, the dour thinker would have cheered up considerably, for here was a model disciple, living proof of his theories, and hope for more good news from the fringe.

[Chapter-Break]

As I travel the peninsula it be-comes evident that a major change in lifestyle is afoot, that the residents’ universe has been disturbed. Only two months ago the entire district was brought under the aegis of Christchurch City Council. Voting on the matter was dominated by Lyttleton, those living elsewhere on the peninsula being a minority. The editor of an independent local newspaper called the affair a scandal, while one resident taciturnly conceded that he could at least now use Christchurch’s excellent library system.

The amalgamation—the big swallowing the small, the homogenous eating up the individual—is now done and dusted. As a result the peninsula, considered the playground of Christchurch, has become the city’s most sought-after subtopia, on a par with the exclusive seaside suburb of Sumner. Not surprisingly, one of the first things to have happened in the wake of these developments is the revaluation of properties. Many residents now fear a massive increase in rates is on the horizon.

We’ve never put a financial value on sea views and open spaces,” Christine Rudin-Jones tells me, “not until now, when the properties have been revalued according to the city standards, even if we still provide most of our own essential services. Suddenly, we find ourselves overnight millionaires and distinctly uneasy about such status.”

The property in which Chris and her husband, Ernst, live is a charming homestead by the sea in the remote and jaw-droppingly spectacular Decanter Bay. In many ways the couple and their home typify the issue at hand, for they are the living expression of the quintessential New Zealand dream.

Chris and Ernst met in Australia, where they ran a home-decorating business. They also campervanned for two years, coming to love the wide-open spaces. When they transplanted their business to Lyttelton, they took to spending their weekends exploring the peninsula, and the day they happened to stay in Decanter Bay the 1851 farmhouse went on the market. They looked at it, at each other, at the small beach and private narrow bay guarded by rocky apostles. The old homestead was derelict, like a ship wrecked on the shore, but its matai frame was solid enough and they had the skills to rebuild the rest. And this they did.

The restoration was a huge undertaking, but as Ernst says with his innate Swiss humour, “We’re seeing the light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s not the oncoming train.” They put their hearts and souls into the job, making part of the house into an exclusive bed-and-breakfast retreat. Ernst could devote himself to his first love—woodwork and furniture-making—while Chris worked as a nutrition consultant, holding tai chi workshops, including a highly popular ACC-endorsed anti-arthritis programme. Their lifestyle is royal but their living has to be eked out. Which is precisely how they like it—no big deals or mega profits, just simple, graceful, day-by-day living. They never planned on being millionaires. Not until a sharp-pencilled gentleman from the city council told them they no longer had any choice in the matter.

Since we’ve been here we’ve seen a trend towards high-price exclusivity,” says Chris. “In Akaroa, some of the local businesses are on the verge of collapsing because they cannot find accommodation for their seasonal staff. [During summer the population of Akaroa swells from 600–700 to some 15,000.] It’s become a ghost town of expensive holiday homes, with the locals emigrating because they can no longer afford to live there.”

Touché! I have seen the very same pattern in Wanaka, where I live, in the Catlins, where a clapboard bach sold not so long ago for close to half a million, in Kaikoura, in Golden Bay everywhere where the scenery can be bought. Therein, perhaps, lies the new New Zealand dilemma. The country may be among the trendiest real estate on the planet, and your own property may be worth millions, but if you don’t want to sell, you may struggle to keep it going. And if you do sell, where will you go instead?

[Chapter-Break]

I’m about to leave the peninsula when big news breaks. Local resident Margaret Mahy has just been awarded the 2006 Hans Christian Andersen Author Award, known as the little Nobel, for her lifelong contribution to children’s literature. I make a few quick enquires. She is happy to meet me.

Mahy, who is 70 this year, has deep roots on the peninsula—her grandparents were born in Akaroa and she has lived there all her writing life, which has now spanned more than four decades. She published her first book, A Lion in the Meadow, in 1969 while she was still the children’s librarian at Canterbury Public Library (today Christchurch City Libraries), and by 1980 was writing full time. Like so many New Zealand high-achievers, she appears a salt-of-the-earth next-door sort of person, unaffected by her popularity. Fame, it seems, like dirty gumboots, is something best kept outside lest it soils the pleasures of one’s personal life. I find Mahy in her Governor’s Bay hillside home, relaxing in front of a glowing open fire with a freshly brewed coffee, reading The Adventures of Peter Pan.

Her open-plan house is so full of books and bookshelves the overwhelming impression is that you have entered a library. Many of the books are Mahy’s own, translated into a score of languages, including Afrikaans, Russian, Chinese and Icelandic. When I ask her how many books she’s written, she isn’t entirely sure. About 200, perhaps more.

Her study, which also doubles as her bedroom, speaks volumes about her approach to writing: there’s yet another floor-to-ceiling bookcase, a computer desk whose clutter beams the message “Do not disturb—many works in progress”, and a tiny bed, relegated to a corner. She often writes through the night, she says, the quiet and lack of interruptions making it easier to enter the realms of the magic and supernatural that she so often evokes in her stories.

It is apparent that she loves not just the stories themselves—though she admits to often being almost possessed by her characters and the events that befall them—but the very sounds and rhythms of words, the music of language. As she reads me some of her poems—one about a cat who ate a poet mouse, which caused his meowing to come out in verse—it is as if there was a musical score underlying the words, an orchestration not just for what to read but how to read it as well.

“Most of my stories are written to be read aloud,” she says. “When a parent reads to a child, there is a special kind of magic being conjured. They can both be transported into the story, experience it together as an adventure. I want to give them the incantations for the journey.”

As for ideas, Mahy says, they are everywhere. The search for keys lost down the back of a chair can lead you into the land of magic; a quirky behaviour of your pet, probed with the question What if?, can be a starting point for an entire novel. Being open to new ideas, receptive to the world and its many layers, has been a particularly rewarding part of her life as a writer. Imagination is a highly potent force, Mahy says. Doorways into Neverland can be found wherever you are.

Akaroa has certainly proved one such doorway for me. As I leave, the tricolour is still flapping, strong and proud, above the quay. Soon, after the tranquillity of the peninsula, Lyttel‑ton will overwhelm with its industrial busyness, the quayside draughtboard of shipping containers, the noise of trains and semis the clangour and diesel grunts of port machinery. There’ll be the row of darkened sailors’ hangouts, the supermarket offering boxing mouthguards on the chewing-gum stand, the nose-piercing whiff of cheap aftershave from numerous barbershops, and the gleaming-white, titanic cruise ship Diamond Princess, disgorging throngs of tourists towards a line-up of buses.

For now, though, all of this is still to come. From the terrace of my habitual café I watch the Noumea-based patrol frigate La Moqueuse at anchor in the harbour, apparently on a goodwill visit, though oddly enough her name translates as “she who mocks” And I recall local novelist and potter Jennifer Maxwell, a kindred Francophile, telling me how, unofficially, Akaroa is still considered France’s southernmost colony, and the supposed goodwill visit is just to make sure things are how they should be.

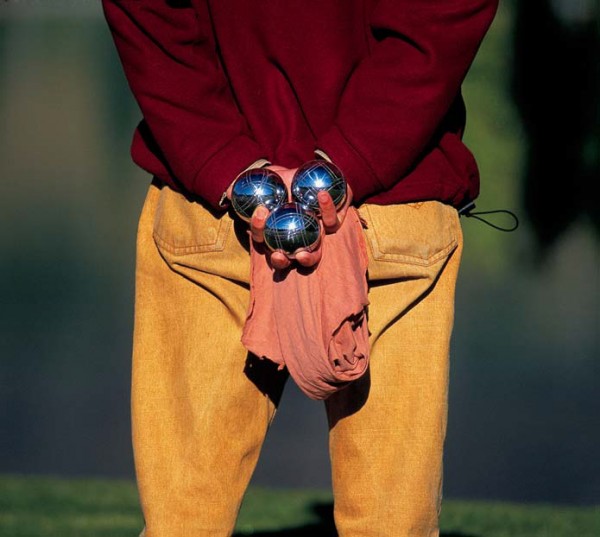

“Nowadays the courteous French naval officers have swapped cannon balls for pétanque boules, and they conquer hearts, not land,” she said. “And how could we resist such charm?”

How indeed? I sip my coffee in the sun, and when, all too soon, it is finished, not wanting to break the spell, I motion to the waitress. When she arrives, eyebrows half-lifted in question, I let the closet Francophile out for one final airing.

“Oui, madamoiselle, j’prends encore un café.”

And she smiles and says, “Tout de suite.”

Or something to that effect.